Corporate personhood is an unavoidable facet of contemporary life. Courts have extended the responsibilities held by humans to institutions, notably in the US Supreme Court ruling Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), which established that non-profits have the right to make legal contributions to political campaigns as part of the rights of “free speech” normally thought to apply to individuals. This legal scaffolding has been since extended to deal with other types of corporate exchanges and responsibilities, and has been linked to corporate tax evasion on a global scale.

The growth of user-generated content and social media, known rhetorically as Web 2.0, has also impressed the logic of corporate personhood onto art institutions. Museums and galleries worldwide increasingly find and define audiences as “Users,” posting institutional announcements on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram using a kind of doublespeak that mimics human speech and personality. (On September 11, 2016, Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum posted to Facebook: “We LOVE seeing the ROM through your eyes. Share your photos with us on Instagram and Twitter and tag us with @ROMtoronto.”) This Usership of art institutions falls in a long chain of corporations coopting modes of interaction and economic exchange more commonly enjoyed by individuals, when doing so is advantageous.

Still, these museum personas represent a more high-maintenance class of User than most individuals. Museum strategies and budgets are tied to impact measurements and data-centric reports that put increasing statistical weight on their social-media reach and engagement metadata. The general implication here is that museums no longer trust themselves to be the arbiters of culture as they react more and more to the popular trends demonstrated by online audiences. While some might say this leads to democratization and a necessary shift away from the standard narrative of the Western canon, a move that might especially attract younger audiences, it may also lead to an echo-chamber effect where consumers (i.e., audiences) are exposed to only those things that might be already likely to please them, while other ideas are pushed out of view down the rhetorical newsfeed.

What happens when community building and crowdsourcing meet in the art institution? The mobile device, and its attendant social-media Usership, become exclusive prerequisites to viewing art and participating in institutional offerings. Often, only the museum or gallerygoer crowds that can afford the latest technologies can get the full experience for viewing and sharing art. Perhaps this is part of why media art and Net art continue to remain fringe genres, as they often require digital literacy or institutional access to be fully understood. At the same time, constricted and corporatized social-media platforms—Facebook, Twitter—sell advertising based on user data, monetizing audience interest in art through the platform-regulated gestures of support, including liking and commenting. One upshot is that increasingly digital-savvy artists, if noticed online, might attract institutional attention without going through the traditional hurdles. On the other hand, art neither intended nor designed for circulation on the web tends not to be judged by its essential qualities and may never be “discovered,” except by the most sleuth-like curators.

In a mad rush to motivate Users and make an impact on the web, museums have sponsored gamified, crowdsourcing projects and ushered in a new breed of social-media driven labour and engagement. The National Gallery of Canada’s Twitter feed, for example, is awash with hashtags such as #Cdnartist, #cdart, #exploreCanada, #discoverOn and #myOttawa, where the museum User links the institution directly to promotional tourism. Patron photographers and tweeters who respond to these initiatives by posting to Facebook or Instagram provide the outsourced labour of publicity, enmeshing their snapshot observations into the numbers game of institutional marketing campaigns. Such visitors also help categorize the institution’s scanned, digital repositories through crowd-sourced metadata projects. Meanwhile, through distance-learning websites, and virtual museum tours, this library enforces the new paradigm of patron as User. The digital archive, for example, is utilized by Wikipedia Edit-a-thons and workshops that assemble participants to assist with entering locative histories contained in art-institution archives or building up the “gaps” in the online encyclopedic record by contributing their own, often specialized, knowledge.

If these institutional-personhood initiatives are taken to their logical extreme, they stand to challenge some antiquated notions of art spectatorship, including the sublime or epiphany-driven art-viewing experience. Still, considering that museums have never before set their standards of success on the feedback they receive from User engagement, with their resources through mediated, third-party apps, we are living through a strange and rapidly shifting reality. The museum-personhood Usership model pushes both artists and institutions toward a flattened plane of discursive action and reaction. The only obvious winner in this complex web of interactions are the digital platforms who codify cultural and economic values, subsuming and automating the authority of more traditional actors, including you, the User.

This post is adapted from an article in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Art.

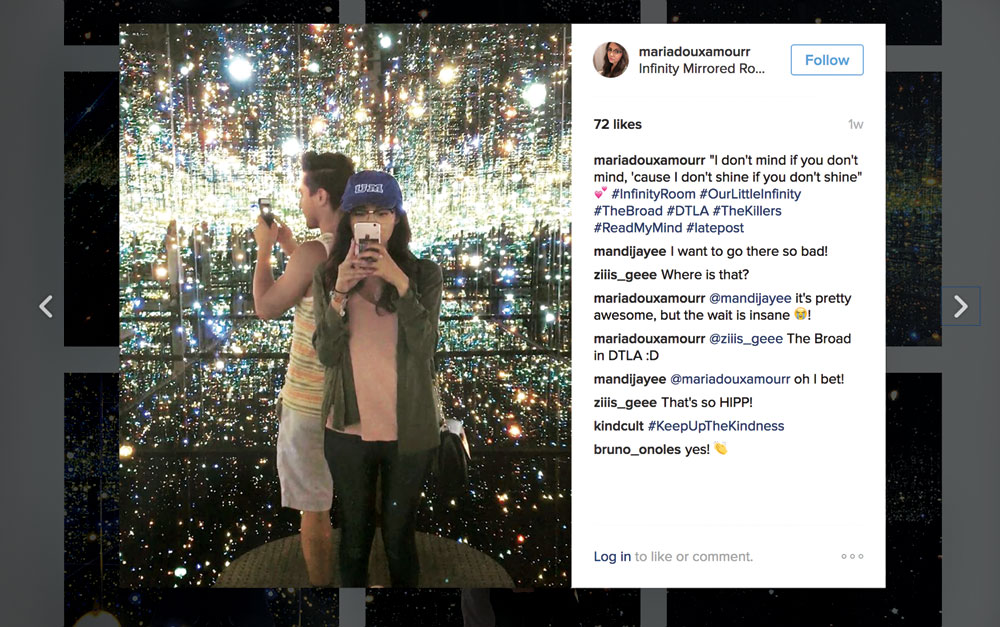

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions

of Light Years Away ,(2013) is one of the most popular artworks to be shared on social media. Courtesy Maria Mena.

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions

of Light Years Away ,(2013) is one of the most popular artworks to be shared on social media. Courtesy Maria Mena.