3. Try to acknowledge that you’ve received a text message.

—“4 Ways to Text,” wikiHow

In Nora Ephron’s You’ve Got Mail, Meg Ryan’s Kathleen lives anonymously online under the pseudonym “Shopgirl,” striving for the rush, the breathlessness of a digital romance. Every morning, New York City’s urbane, klutzy, impatient white woman, the kind typical of a ’90s romantic comedy, patiently awaits the three words that come not from a lover but a stocky home computer—her fingers on the mouse, her wrist pressed on the mousepad, the other hand poking and stroking the keyboard. Screens, with their embedded cameras and mics, threaten to expose; they also afford an erotic anticipation.

The screen turns into skin; sometimes, it makes you plead. It’s a story familiar to most of us. We wait for an email, a text, a string of notifications, protected in a sense by our phone or computer’s tendency for delay. As we wait to receive or deliver a message, screens prompt a self-recognition, a shiftiness in the body to see things clearer—a thrill, or a shame. There are other bodily symptoms caused by our devices: stiff fingers, thumbs and necks; furrowed brows.

***

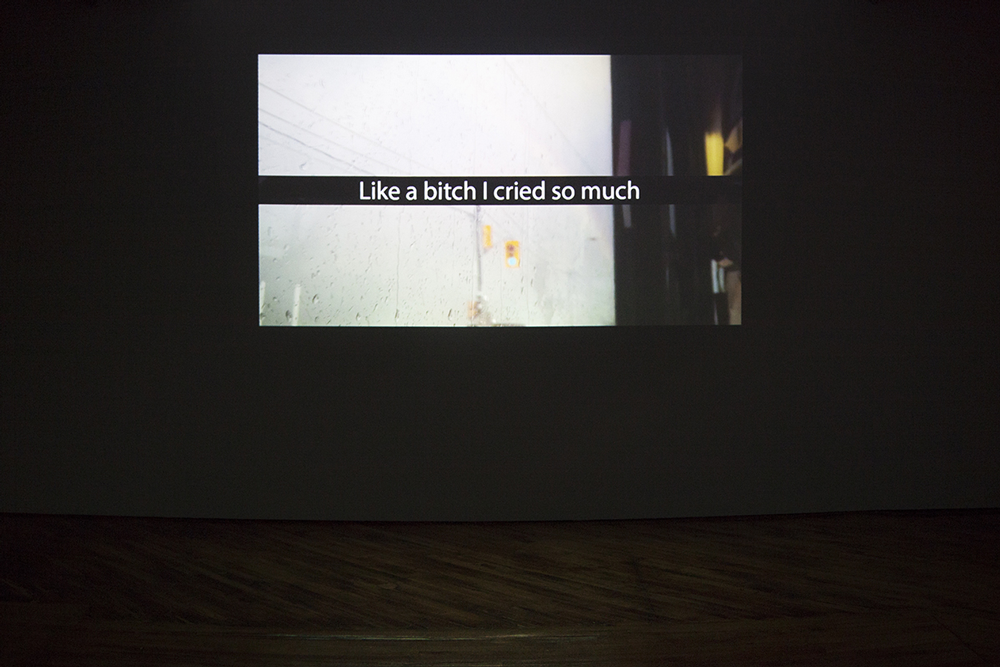

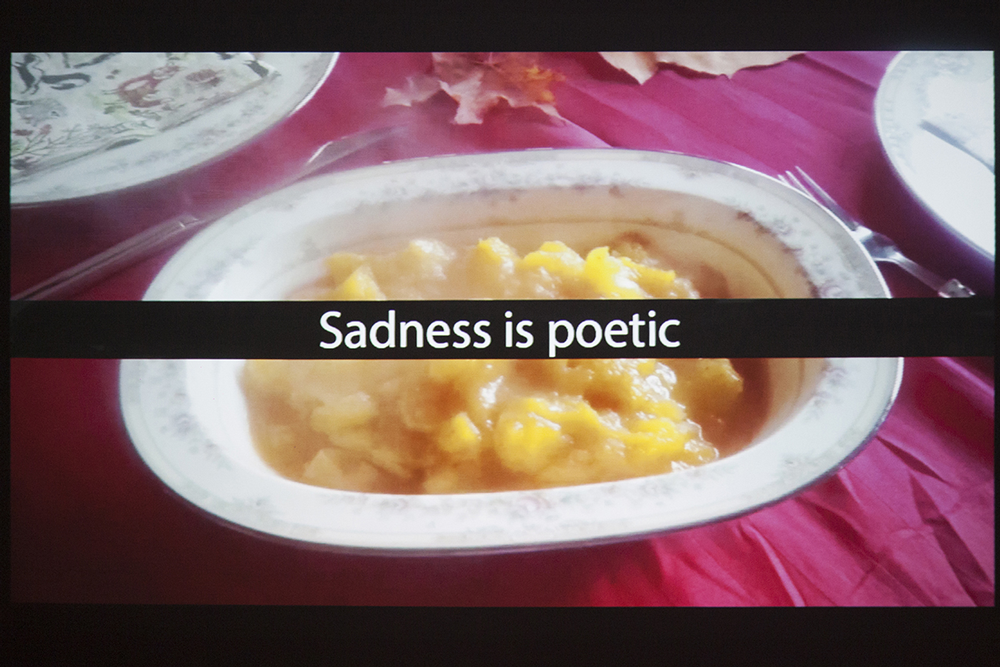

jes sachse, Micro Comedies, Macro Tragedies (installation view), 2016. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

jes sachse, Micro Comedies, Macro Tragedies (installation view), 2016. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

What does it mean to screen the body: reactive, responsive, emotional? “What does it mean to be happy? What does it meme to be happy?” asks the written description of jes sachse’s Micro Comedies, Macro Tragedies (2016), a video screened earlier this fall by Critical Ethics 2016 at Trinity Square Video. The artist documents the everyday—sights mundane and calming, populated and not—as love notes. Pairing moving images with unusual text (words from a conversation between Louis C.K. and Conan O’Brien “on the topic of true happiness” label each clip, like poetic verse), sachse journals their sights on screen like incantations: sachse’s cat gnawing at their arm; the lonely vision of traffic lights from a bus window, bathed in a dull Toronto evening-cloud hue; sachse’s shot of their own face—mouth painted blue, gaze glazed, hair floating—as they lie in a bathtub; their brother and father wheeling them on a wheelchair as the two quarrel through the aisles of a grocery store. sachse captures these moments, emulating the observational documentarian—phone raised overhead, eyes visible one at a time from the bottom right and left corners of the screen.

jes sachse, Micro Comedies, Macro Tragedies (installation view), 2016. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

jes sachse, Micro Comedies, Macro Tragedies (installation view), 2016. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Two shots that remain crisper in my memory play, hymn-like, in succession. “Sadness can be poetic / You’re lucky to live sad moments” titles a late-afternoon image of what looks like a bowl of simmering curry placed on a dining table. Gold like turmeric, the picture both soothes and saturates, evoking a familiar scent and gooey texture. sachse’s phone captures images of a certain warmth, allowing us to experience a food or a being with a sense of healing that homes in on the sad, the hurt.

Perhaps everything the screen captures becomes a little more touchable, attainable, tender. In the artist talk, I asked sachse about their work and how it explores the experience of sadness through screens, to which they replied elaborately, noting that, in the end, “it is all about the sad.” The Sad, they say, as though capitalizing a doctrine. The Sad frames the screen because it stirs a longing: for spoonfuls of a steaming home-cooked meal, or for the touch of a pet. Screened images are sensual betrayals: how close they make certain things seem, and how out of reach.

***

With bated breath, I focus most on the text of a Snap (in Snapchat) because the image won’t last unless I take a screenshot of it. If, while reading an article online, I simultaneously click on another icon or tab, I begin, in those moments of waiting, to quickly gorge on the words of the former. It’s a painfully silent rush. Another icon or tab’s inevitable opening is also a delay. You can’t see everything at once.

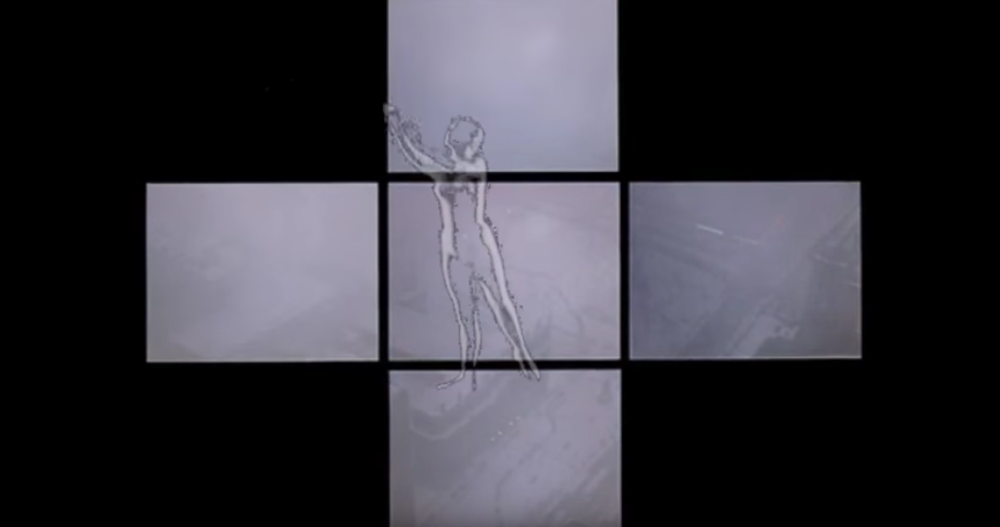

Roman Kroitor, In the Labyrinth (still), 1979.

Roman Kroitor, In the Labyrinth (still), 1979.

In 1967, Roman Kroitor’s multi-screen projection In the Labyrinth showed at Montreal’s Expo. It was the germ of Multi-Screen Corporation, which later became IMAX. Kroitor’s $4.5-million venture was a mammoth disassemblage; the film played simultaneously on five different screens, featuring different sections of the image, while also forming a single mosaic. And while they come together as one, they also transpire independently of each other.

This September, at Toronto’s In/Future festival, Jamie McMillan, Maikol Pinto, Kevin Chaves, Jeffrey Royiwsky and Mario Arnone remembered Kroitor’s project in an untitled digital experimental film that was more work-in-progress than homage. The work screened at Ontario Place’s Cinesphere, appropriately an IMAX theatre.

Here, the screen, split, is a collective noun. In one projection, Toronto-based artist Dahae Song’s face is framed at various angles (profiles side, front, back, centre) as she applies oil on it, and a plush crimson lipstick on her lips. This is followed, later, by a procession, and a restrained, broken marching-band sound. Later, an image of a knife slicing meat with stylish precision in a chef’s kitchen suggests literal dismembering: the screen in shreds. Towards the end of the film, each screen captures a separate image of clouds floating in and out.

Each of the five frames is projected beyond the screen, hinting at the possibilities outside of it. McMillan, Pinto, Chaves, Royiwsky and Arnone’s five-way visuals effectively study a culture of screens by way of screens, tracing the spectator’s transformation from an audience, fascinated, to a member, obsessed.

***

I cracked my iPhone screen today. The tiniest crack. You have to strain your eyes to see the sliver. It looks familiar, like the scar from the cut I got from accidentally scratching a key on my forehead at the age of six, or a vaccination-shot mark, weathering as it hardens on my arm, from the age of eight.

The screen, segmented, is also slightly broken. How do we react to broken screens? Do dents and scars have to be reminders of a fall or a hurt? Or can they also, when created on purpose, have constructive and aesthetic functions?

The five-screen projection by McMillan, Pinto, Chaves, Royiwsky and Arnone depicts a desire for several perspectives on a single screen. The side profile must be supplemented with the front, and the front with what is behind. And yet, even as the one screen cracks symmetrically into five, you lose focus. I stare at my phone, alert yet numb. It happens again, the screen cracking, with the crack svelte but noticeable, like a strand of fallen hair. My perspective is quick, pupils darting from the bottom-right to the top-left.

Multi-screen projection, positioned as stylish, only really makes for a stylish kind of anxiety, an intimacy where perspective is tense, crumbling and not singular. But what if multiple screens were necessary to how we live now? What if my phone were a limb, my laptop little more than a hand rest—my screen, as in moments of sachse’s film, the only space to heal?

In “Fear of Screens,” a piece in the New Inquiry, social-media theorist Nathan Jurgenson critiques Sherry Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation, which argues that young people let go of their smartphones to “embrace humanity,” as if intimacy is digitally impossible. “Physicality can be digitally mediated: what happens through the screen happens through bodies and material infrastructures. The sext or the intimate video chat is physical—of and affecting bodies,” he argues. In likening the screen to the body, the medium becomes alive, filled with soul. Arranging devices—phone in sweaty palm, laptop cushioned on the belly—anticipates a longing for conversation.

Before the screen became populated by multiple tabs, it was home to pre-broadband Internet. The medium in the day was perhaps as much a virtual document of the user’s feelings and dialogues as it is today. Take, for example, Ben Sisto, Josephine Livingstone and Joe Bernardi’s Web Safe 2k16, a self-proclaimed digital “archive of memories.” The website contains writing by precisely 216 writers who narrate their memories of using pre-broadband Internet, connected as it was to VGA monitors and modems of the ’90s. At the time, most screens used Lynda Weinman’s Web Safe colour palette, a series of standardized hues created to ensure that colour on photos appears uniformly across devices.

In this project, the palette becomes an aesthetic for nostalgic millennials; each of the 216 writers write 216 words inspired by one of the finite array of colours. With prose that is both candid and precise, each text foregrounds the pastels, electric blues, pasty greens, milky yellows or soft peaches, each conjuring an intimate memory of colour on the screen, and outside of it. The accounts are memoirs from adolescence, evoking the digital cultures we grew up with, recalling flirtations over MSN Messenger or findings on Geocities. Screens become novelties of the past but in their reinventions, deeply personal, habitual to the body.

As a platform, Web Safe 2k16 is poignantly past tense. For those who view digital lives as emotionally void, these calming, readable, nostalgic writings document our relationships to the digital as a kind of muscle memory. In my reading, I pause, zoning out as the website’s nightly neon glazes; blinding, as it draws.

***

It is wisest and best for an international student to try to simultaneously be both close to their phone (with access to WiFi or data) as well as with someone (a friend, roommate, classmate). For many international students, the two seemingly conflicting habits rarely exist independent of each other. I learned this over the years, living racialized, in a country different from the one of my parents. Treating distance as a bridge rather than a roadblock, they insist and I comply—sometimes, indulge—to keep in touch consistently. WhatsApp bears witness: every Canadian morning, as they go to bed, I must send a “good night!” (or “good morning!” depending on how generous I feel) and, at every Canadian night, a hearty “good morning!”

***

“Video chat brings faces to other faces,” declares Jurgenson, nakedly affirming the feeling of my Skype calls back home. The video-chat feature pixelates the image of family unpredictably; frequently, the connection feels tenuous, fragile.

My screen is an audience. Maybe, it desires attention from me. It’s like the rituals we don’t emphasize but subconsciously prioritize: adjusting a folded shirt collar; rolling up wrinkled sleeves with care; gently feeling with our index fingers around our eyes for any remnants of sleep. If Read Receipts are on, the “seen” but not-responded-to text is as harrowing as it is irrelevant. A photo not taken, because even after various tries the angle is never right, is a common regret. All the selfies deleted; all the tabs on Google Chrome shut before reading; all the texts drafted that don’t get sent. The screen records so much, and often only returns sadness.

The screen cannot save you, but at least it lets you be. I know this in the dark of my room, where I’m most comfortable reading—where the light emanating from my computer screen binds me, and I become a photo, still and consumed. Breathless for a moment, I am Meg Ryan’s Kathleen. Or, I’m in a gallery, transfixed or repulsed by a work of art. I am a boy, looking.

Meg Ryan as Kathleen Kelly in the 1998 film You’ve Got Mail.

Meg Ryan as Kathleen Kelly in the 1998 film You’ve Got Mail.