Clay work is a socially engaged ceramic art practice that is intentional about materiality, pedagogy, community and access. These elements come together to make up the work, such that clay work isn’t solely concerned with the final product or even the creative process. In this piece, we draw on the insights of Black thinkers, organizers and artists to reflect on the possibilities clay work might offer combined with an anti-carceral and abolitionist perspective. People’s Pottery Project, for example, has been operating in Los Angeles since June 2019, offering classes that are free for people who are formerly incarcerated, and low-cost for all others. This artist-driven initiative’s mission is to empower formerly incarcerated cisgender and trans women, as well as other trans and nonbinary individuals and their communities, through art.

When we touch and mould clay, we touch and mould a bit of life itself. Though temperamental and at times brittle before it becomes bonded and hard, clay can be reworked and recycled infinitely before it is fired. The process of working with clay can feel as though it brings us closer to the chaos and perpetual change of life itself. As praxis, clay is the ultimate medium of touch, and also a powerful teacher. No one ever fully escapes or masters the work of touching and feeling. For Kenyan-born British ceramicist Magdalene Odundo, “of all making mediums, clay is the most versatile and pliable and naturally earthly, sympathetic and human.”

Black and Indigenous people find clay in the places where we live to create vessels that tie our histories together.

Ashes to ashes, dust to clay. How do we as Black people find our way to clay? What does it mean to be treated, in life, as though we are closer to ashes than to clay? Borders, police, prisons and courthouses foreclose touch by isolating people from their loved ones and sometimes, as in the case of solitary confinement, from any other beings. Touching clay can help us reach each other and recentre both connection and transformation as we build abolitionist futures together. “Won’t you celebrate with me,” wrote Lucille Clifton, “what i have shaped into / a kind of life? i had no model. […] i made it up / here on this bridge between / starshine and clay, / my one hand holding tight / my other hand.” Her luminous and defiant poem centres both power and deep vulnerability, and it reveals how so much of the work of making up “a kind of life” involves touch—the labour of shaping and moulding, and, sometimes, the act of fumbling in the dark. We hold the labour of survival in our whole bodies, but much of it also rests in our hands.

Domonique Perkins, co-founder of People's Pottery Project, 2020. Photo: People's Pottery Project.

Lauren Fuller, employee of People's Pottery Project Employee, 2020. Photo: People's Pottery Project.

People's Bowl, 2020. Photo: Heather Rasmussen.

People's Bowl, 2020. Photo: Heather Rasmussen.

When thinking about communal clay studios beyond the academy, it’s essential to be aware of site-specificity to avoid patterns of gentrification and recreating barriers that make access to clay facilities a luxury for a privileged few. Being intentional about where these spaces are located and whom they serve might help us work toward equitable futures of clay access and spaces that are welcoming of makers, dreamers and teachers while making room for social practice and experimentation.

As we build networks of care, mutual aid, support and accountability that counter the logics of forced containment and premature death, clay becomes one of the ways by which we collectively return to ourselves and to each other. What might, for instance, a restorative justice process look like if it began with a bag of clay? It could mean creating a vessel to physically or metaphorically hold emotions, memories, intentions, regrets. Clay also provides the opportunity to learn about practices, techniques and ceremonies that are indigenous to the many places we call home: Jebena is a traditional Ethiopian and Eritrean coffee pot made of pottery; an ukhamba is a Zulu brewing and drinking vessel used for sorghum beer; and yabbas have been made, used and sold in Jamaica by people of African descent for food preparation and storage since the 17th century. Clay can be the ground, the container, the frame and the fire where we tell each other our stories, where we rest together and where we slow down. Ceramic artist and teacher Paul Briggs explains: “The spiritual piece for me is the settling down part. Not so much the object, not even so much the process, but the settling down of myself to even do the process.… I settle myself into a particular place and then go to do that work.”

Ceramics can learn from a healing justice framework, which Autumn Brown and Maryse Mitchell-Brody describe as an “all-gender, all-bodied, inclusive and accessible space for practicing and receiving healing that is built in partnership with social justice movement work and sites of political action.” Integrating more clay programs and facilities into community centres and perhaps even bringing them into public schools with healing justice in mind could be transformative—especially if those who are most impacted by structural violence are centred and lead the way: Black and Indigenous trans and cis women, queer, trans, Two-Spirit and nonbinary people, people who are criminalized, people who have been incarcerated, migrants, poor people and people with disabilities.

The object itself, pottery, also holds meaning and promise. French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan wrote that the vase “creates the void and thereby introduces the possibility of filling it. Emptiness and fullness are introduced into a world that by itself knows nothing of them.” Psychologists, psychoanalysts and transformative-justice practitioners alike have used the metaphor of the container to help explain the role of boundaries in shaping individuals. So often we think of our thoughts and feelings as having an interior and exterior relationality that is mediated by the porous borders of our bodies, by the space of our hearts and minds. As much as we are containers ourselves, we benefit from creating containers outside of ourselves: rituals, ceremonies and practices, sometimes mediated by another person. Sharing our thoughts and feelings allows the person listening to return them to us reframed, illuminated or processed somehow.

Abolition and decolonization involve at once reclaiming cultural practices and creating new rituals around accountability, healing and conflict resolution, for example, yet these gestures cannot remain at the level of performativity.

Decolonizing ceramic arts would mean giving land back to Indigenous people and providing land for Black people, centring both groups in access to clay and kilns and the resources required to practice, share knowledge and share the pieces themselves. Decolonizing ceramic arts would mean cultivating the knowledge and means to make our own clay and our own kilns. Decolonizing ceramic arts would mean we might be able to touch each other, which is the very thing that prisons and policing foreclose.

To say that the work of decolonizing will happen within the institutions that created walls around ceramic art is counterintuitive to a deeper change forward. Communities committed to abolition and decolonization need to imagine the potential for a dynamic pedagogy in teaching pottery. A dynamic pedagogy means, for instance, creating networks of care for students and teachers in order to provide a symbiotic and generative learning space. The legacy of African American sculptor Augusta Savage and her pedagogical approach paved the way and created opportunities for aspiring creative Black youth. Following a move to New York in 1932, she began to teach art and founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem. She had a profound impact on her students, many of whom went on to become artists. She instilled in them the belief that in spite of the injustices Black people in America faced, they still deserved to have their creativity nourished and to have a space where they could excel. In 1937, Savage became the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center, a space that played a central role in the development of many young Black artists.

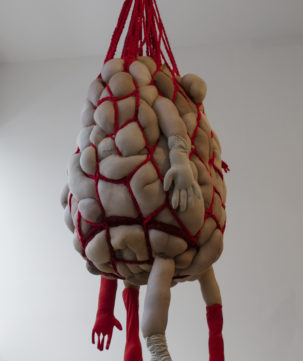

Installation view, Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, The Hepworth Wakefield, 2019. Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield. Photo: Lewis Ronald / Plastiques.

Installation view, Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, The Hepworth Wakefield, 2019. Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield. Photo: Lewis Ronald / Plastiques.

Lastly, a deeper understanding of clay’s materiality can inform our relationship to its ecology and to the land we share. Clay manufacturing on a large scale is entwined with mineral extraction wherein workers mine and process the material; they also transport it as it travels through a supply chain and thus leaves an environmental footprint. An abolitionist clay practice can challenge modes of capitalist production and exploitation by using local clay bodies. The art practice of Carl Beam, an Ojibwe artist, was very much rooted in land and spoke to this commitment to a different path. When he and his wife Ann returned to Ontario in the early 1980s after their time in New Mexico, using clay and pigments local to where they lived became integral. Black and Indigenous people find clay in the places we live to create vessels that tie our histories together. These approaches point us toward something we might hope to one day soon call an abolitionist clay practice.

A group of potters recently drafted a letter to give out when they receive teaching and exhibiting invitations, to determine whether these organizations and groups are actively committed to uprooting racism and all forms of oppression through anti-racist action and policy. But as geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore teaches us: “Abolition requires that we change one thing: everything.” To change everything is to touch everything, which is something we can only do together and by reimagining new forms of sociality. Avoiding the shallow pool of representation politics opens up possibilities in which we find and build common ground in materiality, and then create and dismantle from there. Lucille Clifton reminded us that we are not alone in this work. If we listen carefully, when we settle ourselves to do the work, we can hear that “the waters pulling white men down / sing for red dust and black clay.”

Installation view, Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, The Hepworth Wakefield, 2019. Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield. Photo: Lewis Ronald / Plastiques.

Installation view, Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things, The Hepworth Wakefield, 2019. Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield. Photo: Lewis Ronald / Plastiques.