When I saw Iman Issa’s sculptural installation Material at “The Ungovernables,” the 2012 New Museum Triennial in New York, I thought I’d finally found the perfect Middle Eastern artist—someone who eschewed the tropes of identity politics—because I couldn’t tell she was Egyptian until I read the wall text. I wrote an essay lamenting how contemporary Middle Eastern artists took cues from usual suspects like Shirin Neshat and Mona Hatoum: “They had clearly noted the skyrocketing trend and created blatantly Arabic work to effortlessly cater to it, adeptly yet blindly duplicating what seemed to appeal to [white] collectors.” With the callowness of someone with a naked agenda, I wrote that “[they] made their established predecessors biennial and museum darlings: veiled women, bearded men and Arabic calligraphy in countless manifestations. Have we been regurgitating these instantly recognizable symbols and motifs because they’ve become the sole signifiers/identifiers of our ‘Middle Easternness’ to the West, and all we can do to assert our Otherness now?”

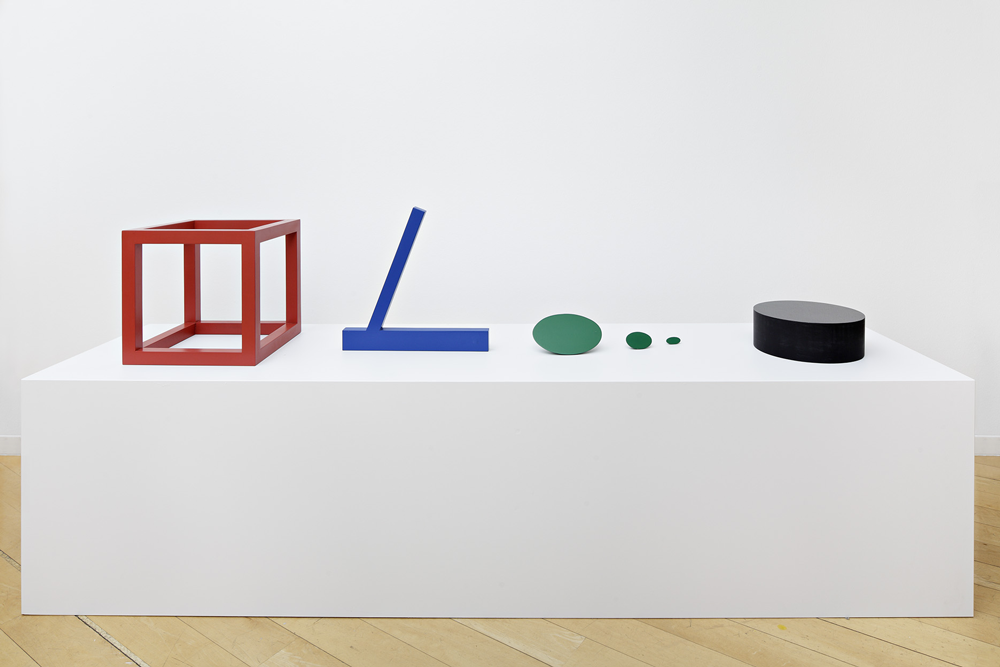

Issa’s Material, which was also exhibited at Toronto’s Mercer Union in 2012, consists of a series of installations of minimalist objects that just barely invoke the language of commemoration—an obelisk, a dome, a vitrine. There is no declaration of time or place, monumentality or anti-monumentality. I went on to posit Issa as “the antithesis to stereotypical contemporary Oriental aesthetics.” I now snort at reading my own writing on being “somewhat startled that an Egyptian artist could so stealthily elude blatant Arabic signifiers yet still manage to interpolate equivocal collective memories and associations.” All these years later, it seems wack that I lauded an artist of colour for exercising a formalism pioneered by white men five decades ago. Was I guileless, seduced?

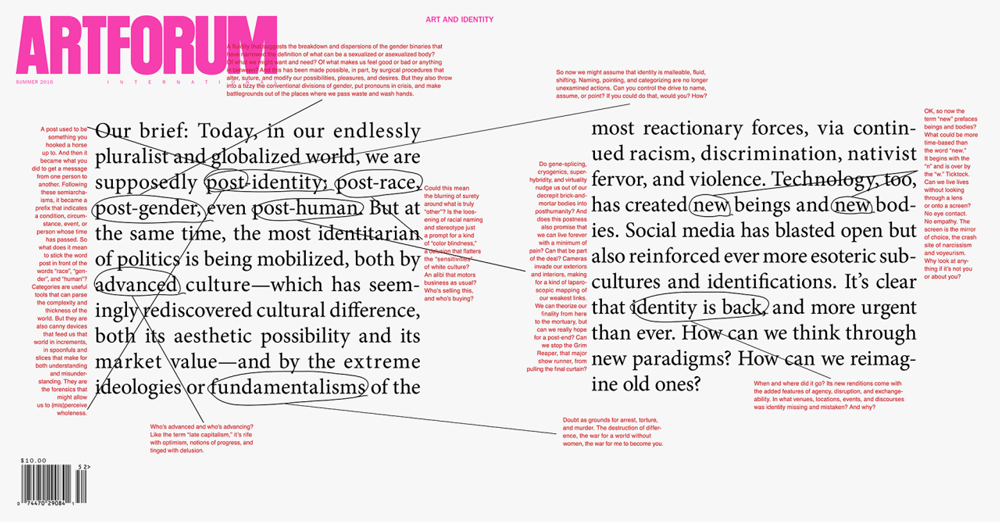

Barbara Kruger, special project for Artforum, 2016.

Barbara Kruger, special project for Artforum, 2016.

Artforum’s summer 2016 “Art and Identity” issue, to which Issa contributed, is the first time I’ve ever felt compelled to read the magazine. On the cover, Barbara Kruger’s special project annotates, and dissects, the issue’s contribution invitation, encircling “post-identity,” “post-race” and “post-gender” to point to the fallacy of putting a “post” prefix on ostensibly rigid, and therefore ostensibly passé, identity categories. I speculate that the same self-appointed critics who think they qualify to declare that we’re post-anything are the same ones who lament—even accuse—artists and exhibitions of a dated, so-called fixation on race. Inside this Artforum issue, in “The Identity Artist and the Identity Critic,” Hannah Black writes that the identity critics “are mad at the identity artists because they think the identity artists are only ever capable of pseudopolitics… The identity critics suspect the identity artist of being opportunistic, of leveraging identity; meanwhile many of them rest high on the plumped psychic pillow of being white, being cis, being a man.”

But social practice equates to social capital more than ever. In a July 2016 piece for Artnews, Taylor Renee Aldridge writes: “Artists have made systemic racism look sexy; galleries have made it desirable for collectors. It has, in other words, gone mainstream. With this paradoxical commercial focus, political art that responds to issues surrounding race is in danger of becoming mere spectacle, a provocation marketed for consumption, rather than a catalyst for social change.” Aldridge wonders “if artists responding to Black Lives Matter are doing so because they truly are concerned about black lives, or if they simply recognize the financial and critical benefits that go along with creating work around these subjects.”

And so it remains true in the art world that anything that comes from anyone who isn’t a white male is somehow relegated to the annals of identity politics, as if white male identity is inherently neutral—i.e. cannot be made into a genre—and therefore apolitical. The same white males who complain about the sudden proliferation of programs and funding streams for people who are not them are essentially parroting a rhetoric not dissimilar to “the immigrants are taking our jobs.”

It is a necessary first step to acknowledge that, obviously, there’s no singular entity of non-whiteness: “people of colour” implies a monolith that is to be consulted, placated, inadvertently and inevitably re-centring whiteness. But English has its limitations, and for lack of adequate alternatives for this piece, I will be using the term BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Colour].

BIPOC artists are given two simplistic and contradictory options: 1. Make identity politics “your thing” as a native informant who epitomizes this category; languish in cultural centres funded by fickle equity grants; risk alienating white audiences; or, 2. Assimilate the language of white formalism; whitewash yourself to be palatable enough not to make white people uncomfortable; risk alienating your predecessors and others like you.

You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. Whippersnapper Gallery took up this conundrum this past May, in “Damned if you do: A Conversation on the Politics of Refusal,” with artists Deanna Bowen and Abbas Akhavan. Not without the requisite disclaimer that “we’re not here to solve anything,” and together with moderator and director of programming Joshua Vettivelu, the panel posed and attempted to answer the following questions: Is your inclusion based on a mandated performance of “identity politics,” so that you perform and reproduce your own marginality to fill out a diversity statistics box on a Canada Council report? Is there an implicit or an explicit expectation for you to perform “your culture” as a native informant, to package the signifiers of your otherness for a white Canadian gaze that thirsts for your otherness/exoticism? If there are, and you oblige, will white critics accuse you of “fixating on race”? When you’re included, are you positioned to serve the institution’s benevolent image as a predetermined placeholder and a representative for everyone like you? Is the hospitality conditional or ambivalent, staged to fulfill an agenda of absolution? Are you permitted to enter, nominally, then told to be grateful to just be there? Has your sense of urgency been pacified? Has your work been flattened to become a prototype that can be trained, that you are obligated to reproduce to guarantee your future inclusion? The answer to all of these questions is yes, more or less.

I’ve been preoccupied with this since the panel took place, continuing discussions with Vettivelu and approaching artists Amy Wong and Duane Linklater for their thoughts on the conundrum. Though sure, we weren’t there to solve anything, I envisioned distilling the contents of the conversation into a provisional list of strategies for BIPOC artists, for which the only precedent I could find is Michelada Think Tank’s #POCSurvivalGuide. Typical artist survival-guide lists, such as Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s mural How to Work Better, Bruce Mau’s Incomplete Manifesto for Growth and William Powhida’s Tips for Artists Who Want to Sell, teem with bourgeois imperatives and platitudes and declarations that ought to end in “if you’re a white man,” ignoring barriers present to intersectional identities. They quickly go from sardonic Internet memes, shared by jaded art-world types and tagged with self-deprecating captions, to Pinterest posters, taken to heart by the kind of people who could read things like the following without scoffing at their own futility: “Don’t borrow money”; “Explore the other edge”; “Stand on someone’s shoulders. You can travel farther carried on the accomplishments of those who came before you. And the view is so much better.”

Here I gesture towards a preliminary compilation of strategies for BIPOC artists. Suggestions welcome.

1. When you’re producing in tundra…

You become the default heavy-lifter; your “hard-done-by-underdog” identity perpetuates your isolation.

Get over it.

“The function, the very serious function, of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being,” said Toni Morrison in 1975. Forty years later, Deanna Bowen says, “You don’t want to embody or embrace that place of singularity because it would undo you;” “Don’t think, ‘Everyone in the art world is white.’ Fuck that,” says Kim Drew, the founder of Black Contemporary Art.

2. When you’re no longer dismissed wholesale, when your identity becomes “your thing”…

You’re mandated to perform “your identity” to fulfill diversity quota; you’re designated as a native informant to a white institution with an absolution agenda.

Question your inclusion.

Know what they want, then withhold it. If you can afford to refuse without adverse effect, then do. You don’t have to explain why.

3. When you’re co-opted by the subjects of your suspicion…

You question contentious funding sources. Should you capitalize on your perceived identity?

Take the equity money and run.

“Should you feel guilty about that? No. Will you be ghettoized? Maybe. Should you feel guilty about that? I don’t think so,” says Bowen. “Guilt is unproductive and immobilizing,” adds Akhavan.

4. When you don’t know why you still strive to penetrate a system that makes you interrogate institutional ulterior motives and therefore your own competence…

Anoint another Trojan horse.

“If we don’t go into those spaces and take those opportunities, who goes in and takes up that space? And what do they say?” says Linklater.

5. When you know there are precedents but you can’t access them, then you doubt the longevity of your current labour…

How do you assume your responsibility as someone who is educated and therefore supposedly upwardly mobile?

Be a creek of your privilege.

Hold the door open. Archive BIPOC-exclusive consciousness raising. Draft intergenerational blueprints.

6. When you’re exhausted from continually agonizing over conundrums that you know your white peers never have to…

Call on your so-called white allies.

It’s convenient to share Black Lives Matter or Idle No More slogans when the news cycle calls for it. Until there are as many BIPOC curators and critics as BIPOC artists, the exhibition and the publication are the ultimate litmus test for whether white people are listening Linklater told me.

7. When all else fails…

Merray Gerges is Canadian Art‘s summer 2016 Editorial Resident.