Nanaimo is a small city of approximately 85,000 on the east coast of Vancouver Island. It was founded on three primary resources: coal, forests and the ocean. Exploring the nuances of these industries and their global connections has been the objective of a series of linked exhibitions curated by Jesse Birch at the Nanaimo Art Gallery.

Birch’s interest in Nanaimo and its history is both personal and academic. Birch grew up in Nanaimo, where he realized that the city celebrates its natural resources in place names and monuments, but also tends to “celebrate and ignore its history at the same time.”

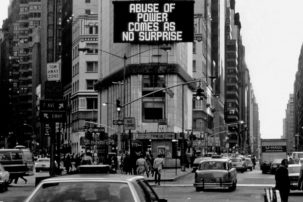

The first exhibition of this series, “Black Diamond Dust,” considered the coal-mining industry and all that entailed from its “fragmented communities through economic development, racial segregation and labour inequity.” Birch enlisted artists Raymond Boisjoly, Kerri Reid, Scott Rogers and Peter Culley to explore this history through photography, video, site-specific installations and poetry.

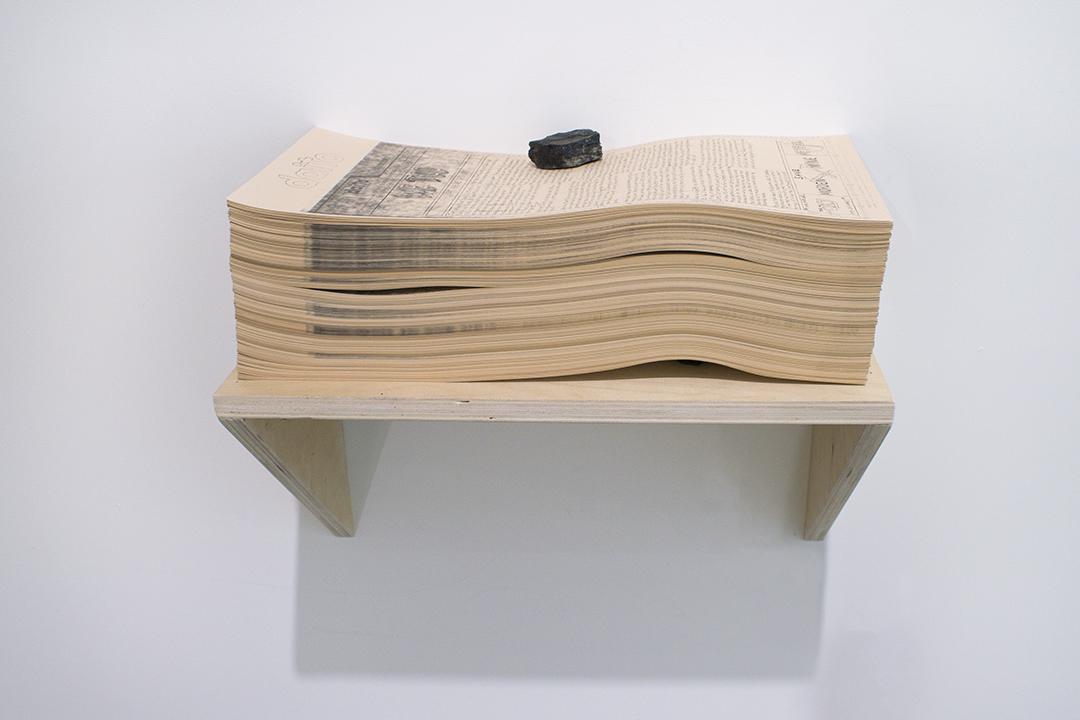

Scott Rogers, We Too (2014 Edition). Open-edition newspaper printed with both a ca. 1940s Gestetner machine and a contemporary photocopier. Text by Eileen Wennekers, and illustrations and technical support from Justin Gradin.

Scott Rogers, We Too (2014 Edition). Open-edition newspaper printed with both a ca. 1940s Gestetner machine and a contemporary photocopier. Text by Eileen Wennekers, and illustrations and technical support from Justin Gradin.

The second part of the trilogy, “Silva Part I: O Horizon” and “Silva Part II: Booming Ground,” addressed the forestry industry and followed a “thematic path from the microcosms of the forest floor, to the quantifying and processing of lumber, to the global distribution of forestry products.” These exhibitions incorporated the work of 18 contemporary artists including Duane Linklater, Marian Penner Bancroft, Kika Thorne and Liz Magor.

Next year, Birch will close the trilogy by looking at fisheries, oceans and the harbour and asking “what it means to live on an island,” a question that will guide the gallery’s programming throughout the year.

Since taking his position as curator at the Nanaimo Art Gallery, Birch—as an alumnus of the University of British Columbia’s Critical and Curatorial Studies program and a past fellow at the de Appel curatorial program in Amsterdam, and as the former exhibitions curator at the Western Front in Vancouver—has followed a highly conceptual and integrative exhibition program.

All of his exhibitions feature multiple contemporary art practices with a strong emphasis on video, photography and collaborative projects. Like many contemporary curators, Birch sees parts of his work as “research.” He takes a particular theme or art practice and explores it along with a select group of artists. In an interview for this article, Birch explained that as a curator he “sets the context” and, with the artists, “builds an experience” for the viewer. His aim, he says, is often to engage the viewer in the thematic questions of the exhibition by providing an accessible entry point and a “way in through the familiar.”

While thematic subjects such as coal, forestry and ocean resources provide familiar touchstones for Nanaimo residents, Birch’s contemporary programming, his selection of artists and a number of major changes at the gallery over the past four years—professional and aesthetic—have created a certain tension in this small community.

In 2011, the institution’s board of directors developed a new strategic plan that would substantially re-shape the tenor of Nanaimo’s only public art gallery. At that time, the gallery had two locations: its original site on the Vancouver Island University (VIU) campus (established in 1976) and its downtown space in a repurposed bank building in the heart of Nanaimo’s arts and business district that was opened in 1999. The direction and management of these two spaces changed often over the years, with the only constant being a part-time curator seconded from the VIU visual arts faculty.

An installation view of “Spirit Gum,” the first exhibition at the Nanaimo Art Gallery after the merging of the two locations in 2015.

An installation view of “Spirit Gum,” the first exhibition at the Nanaimo Art Gallery after the merging of the two locations in 2015.

The downtown location was, from the beginning, dedicated primarily to the exhibition of local professional and amateur artists, while the campus location featured student, faculty and professional exhibitions—the most notable in recent years being a Gu Xiong installation (2011), a site-specific project by Nathan and Cedric Bomford (2013), a touring exhibition of Takao Tanabe drawings (2014) and “Reconciling Self,” an exhibition by Connie Watts, an artist of Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw and Gitxsan ancestry. All of these exhibitions were curated or organized by VIU faculty. The campus location, however, always struggled to gain visibility, and the separation of the two spaces only complicated the gallery’s image in the community.

In 2012, the board realized it needed to direct its efforts on the downtown location, re-focus on its primary mandate to exhibit professional contemporary art, and plan, long-term, for a purpose-built Class A gallery—something other small cities such as Kamloops, Prince George and Whitehorse already had in place. The board hired executive artistic director Julie Bevan—another graduate of UBC’s curatorial program. This was followed by Birch’s arrival in 2014, the renovation of the downtown gallery, a paring down and revamping of all gallery programs, and, by 2015, the relocation of all gallery activities to the downtown space.

After spending a year as interim executive director, Birch became the gallery’s first full-time professional curator in 2015. Today, Bevan explains, the gallery better realizes its purpose—to present “contemporary exhibitions that challenge and inspire the community through art, and which develop and support professional practice.”

The renewed focus on a contemporary and professional mandate has resulted in a tremendous increase of economic and cultural capital for the Nanaimo Art Gallery. Before the transformation, NAG operated the two locations with a very limited budget sourced primarily from the university, the city, BC Gaming and the BC Arts Council. Applications to the BC Arts Council for increased funding were unsuccessful and the NAG rarely succeeded in gaining Canada Council funding.

Today, as Bevan explains, “we have had an overall boost from all levels of government. City support has doubled…and Canada Council has supported us via project grants.”

In an e-mail, Bevan relates that the gallery now operates with a budget of just over $500,000; a small figure relative to other city galleries, but one that has allowed NAG to “more than double” its investment in exhibitions from approximately $70,000 in 2012 to over $200,000 last year.

“The ambitious and meaningful projects that our team has initiated with artists have resonated with funders and juries, which has allowed us to do a bit more,” Bevan says by way of explanation.

Similarly, since 2013, positive response from government agencies has affirmed the value of the gallery’s efforts, and exhibiting nationally and internationally recognized artists like Shannon Bool, Ron Tran and Duane Linklater has also put Nanaimo and NAG on the national art map. For the first time in its history, exhibits at the gallery have been reviewed in the national art press, including this magazine.

Cedric and Nathan Bomford, The Claim, 2013. Installation outside the Nanaimo Art Gallery.

Cedric and Nathan Bomford, The Claim, 2013. Installation outside the Nanaimo Art Gallery.

And yet, not everyone is happy with the changes at the Nanaimo Art Gallery—particularly some in the local community.

Dennis McMahon, a self-taught photographer, petitioned the city in June to consider providing an art center that would do what the gallery used to do—support local artists. He says that he recognizes that the institution has “changed its mandate” and now “only accepts a certain standard and follows CARFAC guidelines.” The “unintended consequence,” he points out, is that it has “removed exhibition space from community artists.” Many professional and amateur artists like McMahon, who have supported the gallery over the years and enjoyed exhibiting their work in the two locations, have been sidelined by new exhibition criteria and a lack of alternative space.

But another Nanaimo resident, Sara Robichaud, a professional painter with an MFA from the University of Victoria, is excited about the changes at the gallery. She says she is pleased to see a more “rigorous and professional level of programming” there. “It is something Nanaimo has needed for a long time,” she says.

At the same time, Robichaud notes that she also hears from her students and other artists in the community—both professional and amateur—who are frustrated by a curatorial approach that has been heavily weighted on artists from outside the community and features art that some find inaccessible. Robichaud notes that “people are hesitant to criticize what they also see as a positive change at the gallery.”

For his part, Birch admits there has been “some resistance” to the new approach initiated at the gallery by the board and staff. He says he views this resistance as “normal,” especially “when there is a shift in a space, when people have to move into a different context.”

In a small community where different factions are in close proximity—and in a wider art community where relationships are, more explicitly than ever, a form of capital— the “normal” tensions that come with a “shift in space” are often difficult to express openly.

The tensions over the Nanaimo Art Gallery’s transition are not only about the loss of exhibition space; they are also about how contemporary art is being defined through the space for the community. Contemporary art is a widely varied beast that consists of multiple art forms and practices. Its definition is extremely flexible and open. Since the 1990s, the curator has become the primary arbiter and mediator of this definition. And, with the growth of professional curatorial programs, the definition of contemporary art has become more global and uniform. These new curators, trained in Canada and elsewhere and, like Birch ending up at regional art galleries, bring a global approach that does not always sit well with the local community, especially when there is only one public space to represent the community’s artistic interests.

Larger cities, such as Vancouver, where Birch worked on and off for about 20 years before returning to his hometown of Nanaimo, have the capacity to host a broad range of exhibition spaces. Some spaces, like the Western Front or Centre A, cater to a particular sub-genre and a small sector of the art-viewing public, while others, like the Vancouver Art Gallery, have the capacity to present a wider range of contemporary practices. Larger cities also offer an array of alternative spaces for every level of artistic practice, from amateur to emerging contemporary artist. With only one small public space, Birch admits that “we can’t be everything to everybody”—a point that McMahon also echoed in the interview for this article.

Like its other resource industries, Nanaimo’s venture into exhibiting contemporary art brings it into conversation with larger and sometimes more powerful partners; national and international institutions that often favour certain artists, practices and theoretical approaches. The challenge for a small city gallery and its curator is how to negotiate these global norms with local expectations. The global outlook of a curator like Birch may bring some difficult changes, but it also introduces the gallery and the city into relationships with artists, galleries, museums and curators from across the country and around the world. In September, for example, the Berlin-based art publisher, Sternberg Press, will issue Black Diamond Dust, the first of three books on Birch’s resource-inspired exhibits at Nanaimo Art Gallery. Partnerships such as this expand Nanaimo’s global presence but also raise the question of how a “small city on the side of Vancouver Island” (as Birch calls it), or any community for that matter, can participate in this larger conversation while still celebrating its own creative resources.

Marie Leduc is an art historian, writer and curator who holds an an inter-disciplinary PhD (art history and sociology) in Visual Art and Globalization from the University of Alberta. From 1998 to 2007, she was director-curator of Keyano Art Gallery, the only public art space in Fort McMurray, Alberta. Marie now lives and works in Nanaimo.

Aerial view of downtown and central Nanaimo and adjacent islands. Photo: Ken Walker.

Aerial view of downtown and central Nanaimo and adjacent islands. Photo: Ken Walker.