Last summer, Canadian Art reported on the government of British Columbia’s announcement that it would give $10 million to fund the Chinese Canadian Museum (CCM) in Vancouver. In August 2020, the CCM opened at a temporary location with its exhibition “A Seat at the Table.” The show is hosted at the Hon Hsing building in Chinatown, with a companion exhibition of the same name on view at the Museum of Vancouver. Co-curated by Henry Yu, Viviane Gosselin and Denise Fong, the shows present work by contemporary artists such as Judy Jheung and Stella Zheng alongside historical documents and videos to tell the stories of Chinese Canadian immigration. Elsewhere in Vancouver, the exhibition “Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” curated by Montreal artist Karen Tam, opened at Griffin Art Projects in January. Tam’s exhibition similarly presents a history of Chinese people in Canada through archival materials, drawings and photographs, but places emphasis on creating a dialogue between art practices of the past and those of the living Chinese Canadian artists featured in the show.

I followed the development of “Whose Chinatown?” with a keen interest before contacting Tam to discuss the timely significance of her project. These initiatives, the creation of the country’s first Chinese Canadian museum and the opening of these exhibitions, could not have come at a more important moment. The COVID-19 pandemic has struck North American Chinatowns in multiple devastating ways, with rent increases, business closures and gentrification exacerbating economic barriers, as well as heightened anti-Asian racism resulting in violent attacks on Chinese people. Henry Heng Lu wrote about some of these issues last spring, expressing the importance of Chinatowns and what is at stake for their residents if the shops, banks, community centres and grocery stores of their neighbourhood disappear. Tam and I were both born in Montreal and have spent much of our lives in and around Chinatown. Here, as in Vancouver, it is difficult to remain optimistic about the preservation of Chinatown when gentrifying taco restaurants and tiki bars continue to pop up within its gates.

“Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” 2021. Griffin Art Projects installation. Photo: SITE Photography. (From left, work by: Linda Zhang, Gim Foon Wong, Stephanie Chong & Bryce Quan, Unity Bainbridge, Jim Wong-Chu)

“Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” 2021. Griffin Art Projects installation. Photo: SITE Photography. (From left, work by: Linda Zhang, Gim Foon Wong, Stephanie Chong & Bryce Quan, Unity Bainbridge, Jim Wong-Chu)

But when I spoke to Tam about “Whose Chinatown?,” she reminded me of what happened in San Francisco. After their Chinatown was completely destroyed in the earthquake and subsequent fire of 1906, it was strategically rebuilt in a self-orientalizing architectural style that set the standard for other North American Chinatowns that came after. I say strategically because it was thanks to the decorative pagodas and dragon gate—a design overseen by businessman Look Tin Eli in the image of the Westerner’s idea of the exotic Orient—that the community could keep their Chinatown and survive within it. It became a welcoming amusement-park-like version of the neighbourhood previously known for drugs, gambling and prostitution.

This technique of self-orientalizing for the sake of survival is one that I find both fascinating and complicated. In “Whose Chinatown?” there are a number of ephemera from the 1940s and ’50s on display: matchbooks, teacups and souvenir postcards made by the restaurants and nightclubs Bamboo Terrace, Mandarin Gardens and W.K. Gardens. The fonts and designs of these objects play into the same visual language of San Francisco’s Chinatown with the goal of appealing to mass audiences. But what is the cost of capitalizing on this construction of the non-threatening “Other”? The model minority myth is fuelled by our complicity in and propagation of the image of ourselves as invisible subjects—easily pushed aside, overlooked and consumed. Cathy Park Hong puts it best when she writes in Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (2020) that “the indignity of being Asian [in the United States] has been underreported…. We keep our heads down and work hard, believing that our diligence will reward us with our dignity, but our diligence will only make us disappear.” Contemporary artists of Chinese descent, including Tam herself, continue to reflect on the problematics of this phenomenon in their work. To aestheticize one’s identity in an artistic practice in a way that pushes back against rather than fuels racist stereotypes is a delicate balancing act. While promoting a stylized foreignness or Chineseness might have been effective at one point, how does it hold up as a strategy to combat systemic racism today? What new strategies and approaches to this dilemma are artists presenting us with? Can our Chinatowns survive the new issues they face, and how can the artist community contribute to their preservation and invigoration?

“Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” 2021. Griffin Art Projects installation. Photo: SITE Photography. (From left, work by: Suzanne Girard, Paul Yee, Linda Zhang, Paul Wong, Fred Herzog)

“Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” 2021. Griffin Art Projects installation. Photo: SITE Photography. (From left, objects from the collections of Karen Cho, Karen Tam, Imogene Lim)

“Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections,” 2021. Griffin Art Projects installation. Photo: SITE Photography. Collection of Tom Carter.

“Whose Chinatown?” takes advantage of the three rooms at Griffin Art Projects to divide works into spaces that represent how traditional association buildings in Chinatowns are organized. The entrance or “storefront business” space includes a book work by Marlene Yuen about the Ho Sun Hing Printers, a company that closed in 2014 after more than 100 years of operation, next to a display of seal chops, inkstones, scales and other artifacts from the collection of research consultant and social scientist Nathan To. These recall the families and staff working in Chinatown. In the “home and residential” room, artworks by Emily Carr, Paul Caron and Unity Bainbridge depicting Chinatown and Chinese people hang against blue-and-white wallpaper whose design is based on hand drawings by Tam of subjects and sites that juxtapose her view of Chinatown with theirs. Finally, the third room—or “society and community hall”—holds the most works, and includes a sculptural installation by the collective aiya哎呀!, which takes the form of a large red, pink and yellow cluster of written messages memorializing the dismantled Harbin Gate in Edmonton; Linda Zhang’s imposing sculptural model of Toronto’s East Chinatown gate, complete with an accompanying board game that comments on the neighbourhood’s architectural vulnerability; and Paul Wong’s 限华 Chinese Only (2018), a neon sign that casts a warm yellow glow across other works in the room.

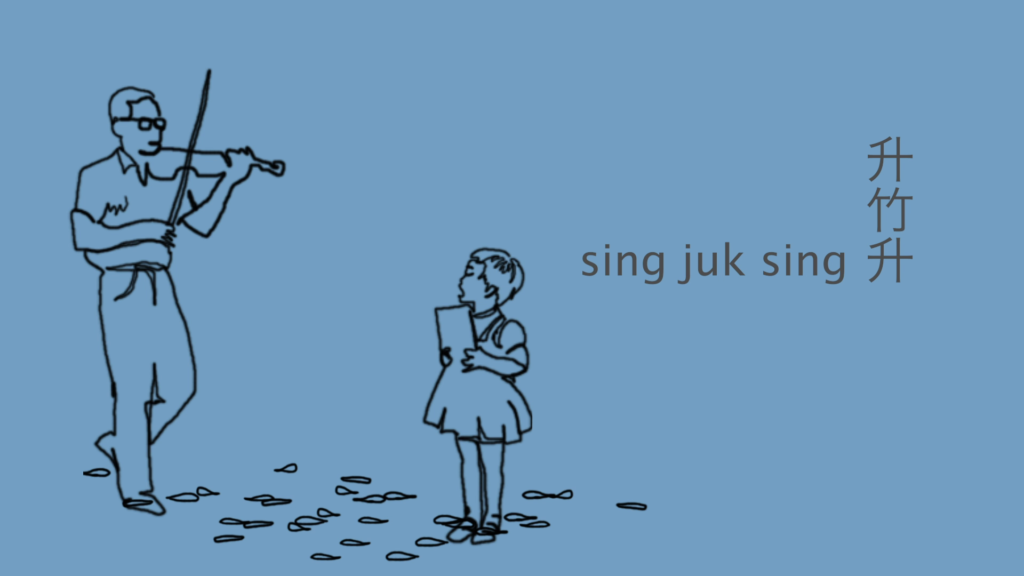

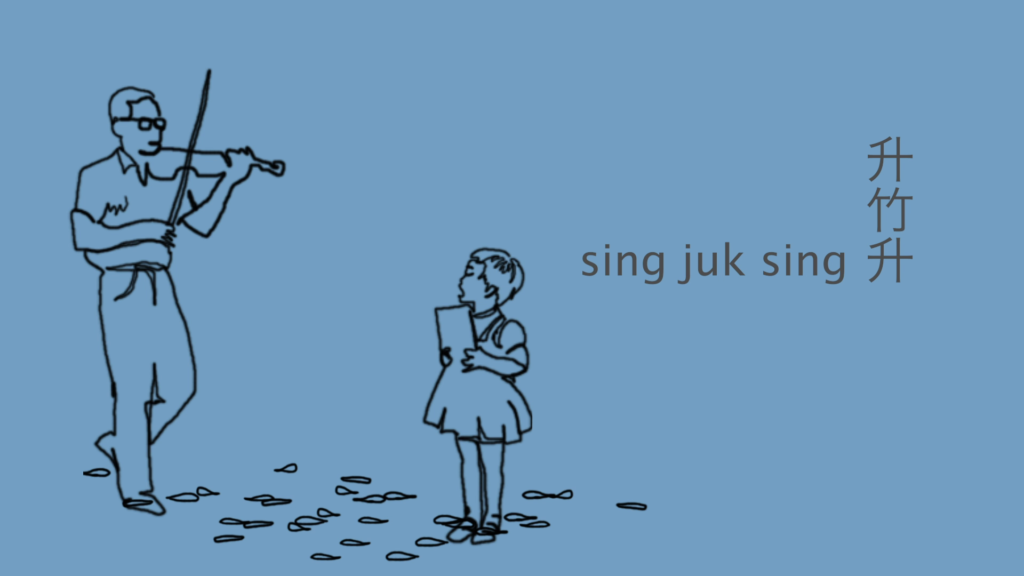

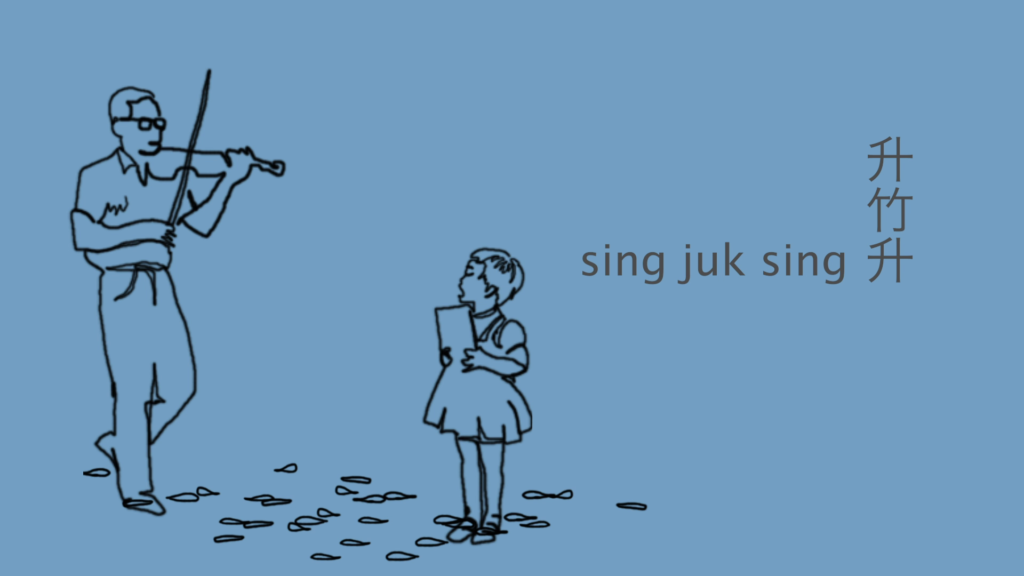

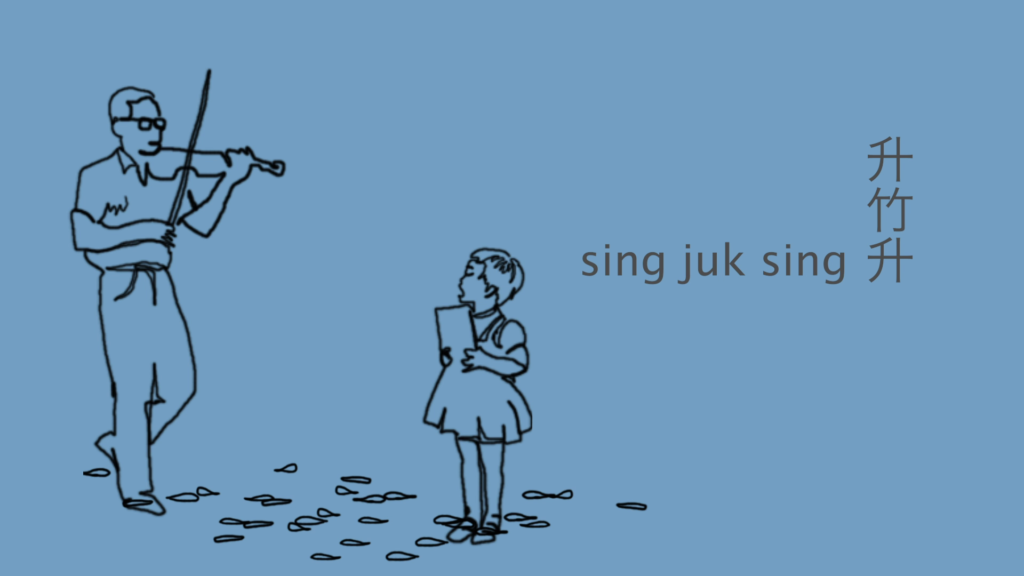

While many of these artists and organizations have exhibited in mainstream galleries and museums before, it is another thing altogether to have 29 of them in a space dedicated to what Tam calls the beginnings of a Chinese Canadian art history—“though not necessarily ‘the canon,’” she clarified to me. Photographs make up a large part of the show to highlight changes to the look of Canadian Chinatowns over time, as well as how figures like Yucho Chow in the 1930s and, later, Jim Wong-Chu in the ’70s and ’80s, chose to document their communities. These historical images seen next to contemporary works—photographs by Morris Lum; a parody real-estate-development sign by Friends of Chinatown Toronto; a video series by Stephanie Chong and Bryce Quan that documents the lives of Chinatown residents and business owners—demonstrates a politically engaged community of artists. Across from the Beatrice and Raymond Jai Collection of Cantonese opera photographs, which span the 1930s to the 1990s, is a video projection of Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (2010/20) by the father-daughter artist duo Mary Sui Yee Wong and Master Toa Wong. Sing Juk Sing is mainly a meditation on the fear of singing and the artists’ relationship to one another, but it also includes footage from their collaborative performance at Montreal artist centre OBORO in 2010. Mary Sui Yee Wong and Master Toa Wong are, respectively, my mother and grandfather.

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.

Like many Chinese Canadians, my family history is deeply entwined with that of Cantonese opera in this country. When my grandfather immigrated to Vancouver in 1960, it was because the Jin Wah Sing Musical Association (established in 1934) sponsored his immigration papers and hired him as their sifu, or master musician. The 1885 Chinese head tax and 1923 Chinese Immigration Act had continued to have lasting discriminatory effects on Chinese immigration to Canada, such that it was still complicated to immigrate as a family well into the 1960s. This legislation was the reason Chinatowns were mostly male spaces, and this imbalanced sex ratio contributed greatly to the white fear, embedded in the racist phenomenon of Yellow Peril, that East Asian men were as much a sexual and racial threat as they were a social and economic problem. My grandfather became a member of the growing community of men living a bachelor’s life in Vancouver’s Chinatown, except that he was not a bachelor. It was only on my grandmother’s insisted request that she, along with my mother and her two siblings, finally joined him in 1963.

They lived together in Chinatown for several years, through a fire in their building and other daily threats to their safety, until they finally saved enough money to buy a house in a different neighbourhood. My Chinatown experience is a far cry from those of my mother and grandparents. Because of them I had the privilege of growing up with “insider” access (despite my mixed ethnic background) to spaces like the makeup room of amateur performances put on by Montreal’s Yuet Sing Cantonese Opera Company. There I became intimately acquainted with the distinct smell of glue made from poplar-tree bark that is applied on hairpieces worn by performers. I spent many evenings immersed in the loud clashing cymbals and other percussive instruments that form the signature sound of Cantonese opera music. To me, Chinatown is not only a place for dim sum and grocery shopping. It is also where I get to see my uncles, aunties and elders who by day work at the garment factories and restaurants, and by night perform on stage in their full regalia or play in the orchestra.

Throughout the Griffin Art Projects gallery, it is possible to hear my grandfather playing his erhu, a centuries-old instrument that makes up the soundscape of Chinatown even today, where you might walk past a doorway and hear an opera ensemble practising, or the deafening sound of mahjong tiles being shuffled. Cantonese opera is a form of artistic expression and entertainment that captures the spirit of togetherness that I feel about Chinatown as a place in general. The exhibition “Whose Chinatown?” gathers intergenerational voices of activists, business owners and workers, families, artists and collectors in much the same spirit. While it can be difficult to adopt a visual language or aesthetic that emphasizes an ethnicity without perpetuating stereotypes, I read exhibitions such as this and the artworks they present as evidence of a necessary return to the creative strategy behind the rebuilding of San Francisco’s Chinatown. It is a conscious effort to combat what journalists predict, as Adam Curtis has in his new documentary series, is a re-emergence of Yellow Peril, or a renewed existential fear by Western powers of revenge by the “Other.” Centring Canadian Chinatowns as vibrant sites of living cultural heritage and presenting the potential beginnings of a Chinese Canadian art history are important acts of embracing and caring for our communities. I asked Tam about what she hopes audiences will take away from the show. “That Chinatowns are still dynamic,” she said, without hesitation. “That they are living organisms, and people still live and work there.”

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.

Master Wong Toa 黃滔老師 and Mary Sui Yee Wong 黃瑞儀, Sing Juk Sing 升竹升 (video still), 2010/2020. Filmmaker/co-editor: Marlene Millar. Video, colour, stereo, 8 min.