In the fall of 2019 I was granted a fellowship at the University of Victoria to go through Aiyyana Maracle’s contribution to the university’s transgender archives. It was a transformative and heartbreaking look at what Indigenous artmaking was like for trans women in the 1990s and early 2000s. Through her journals and correspondence, I saw that many prominent Indigenous artists and writers had worked with Maracle and had been in conversation with her. Yet Maracle’s contributions to Indigenous art and the lives of trans women in so-called Canada have been largely downplayed, which was disheartening, but not surprising, to witness. Any form of canonization, including Indigenous art canonization, is complexly coded with power differentiation that marginalizes trans women. Maracle’s archive shows that, for decades, trans women have not been afforded space within fields such as Indigenous art, literature, academia, and feminist and lesbian communities.

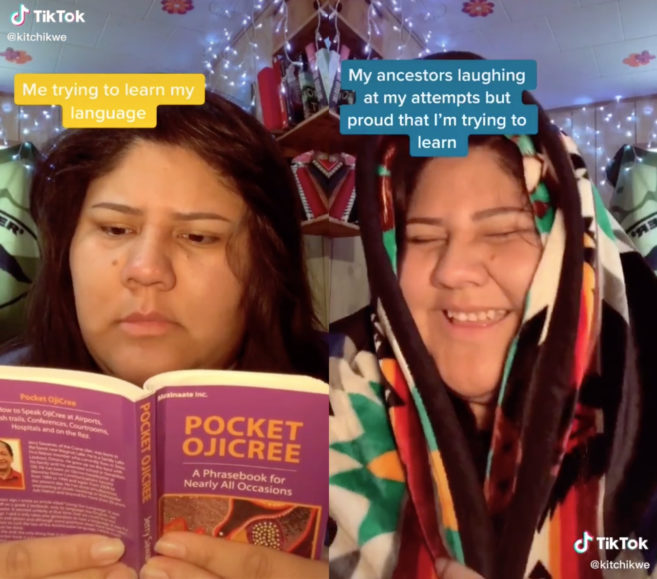

Aiyyana Maracle, Indian Acts Cabaret (performance documentation), 2002. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

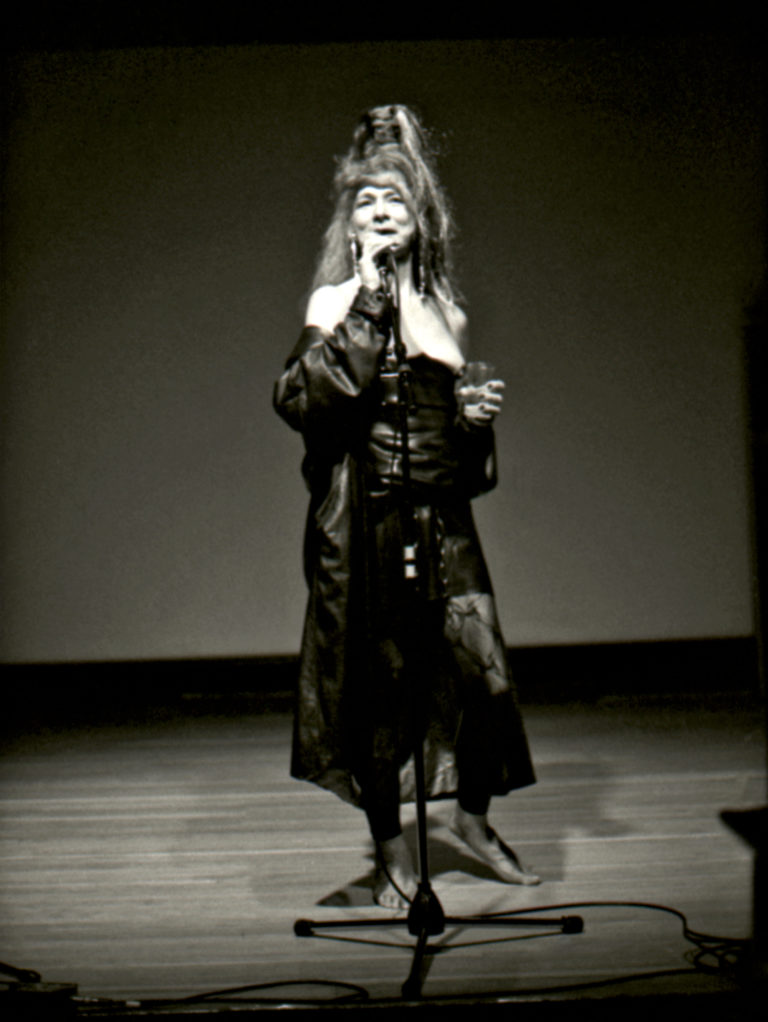

Aiyyana Maracle, Indian Acts Cabaret (performance documentation), 2002. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

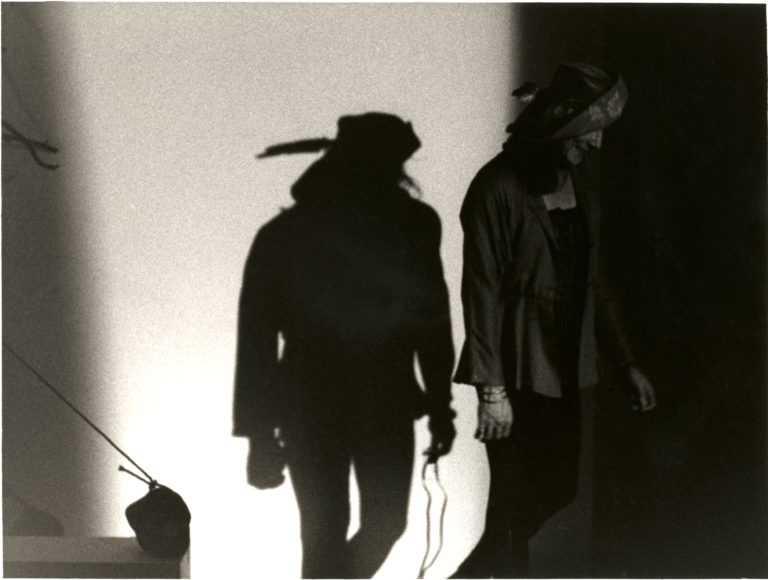

Aiyyana Maracle, Strange Fruit (performance documentation), 1994. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

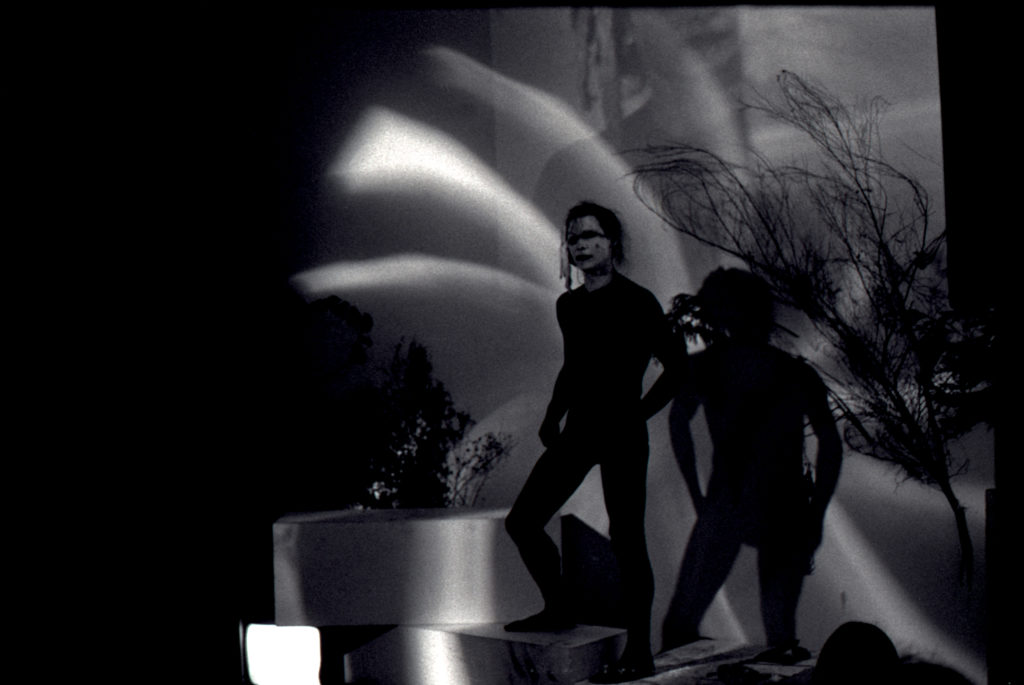

Aiyyana Maracle, Strange Fruit (performance documentation), 1994. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

I was intimidated going into Maracle’s archive. Coming into an archive as an Indigenous artist often felt difficult. Though I was a fellow accompanied by an assistant professor, the archivists treated me like I was a kid doing a school project, or like I had gotten lost. It was a reminder that though our bodies are a part of the archive, trans and Indigenous people are not supposed to be in the archive as researchers. There is also a lot of anxiety and authority that comes with having access to the things someone owned and created. Maracle’s archive included personal items like clothing, bones, pearls, shells and stones, which evoked complex feelings for me. It was wonderful to interact with objects that were personal to her. Touching her things made me feel like I was learning so much about how she and I work in similar ways. I was touching the objects that were meaningful to her, but I’ll never know why or how they were meaningful. Seeing Maracle’s clothing was another reminder of how much access we have to her. These clothes and small objects are a reminder of her humanity within the archive; among all the files, the writing, and the art also live the simple, mundane aspects of her life.

I saw an item labelled “Smallpox Blanket,” which consisted of three strips of red fabric that had been burned. I was shocked at how it had been stored within the archive, with parts of it crumbling in the paper bag it was wrapped up in. I realized how objects like this can’t be stored forever, and will eventually be lost. I can’t help but think about how our work and lives as Indigenous trans women are being lost, unspoken. As a young trans Indigenous person, I know why Indigenous peoples aren’t talking about Maracle’s work. It’s the same reason these people seldom speak about the work of trans Indigenous women now. People want Maracle to not exist, like they want trans women to not exist. When you push back at transphobia, you are pushing back at the norms of Indigenous community, erasure, canon, Indigenous scholarship and an institutionalized vision of Indigenous art. That’s dangerous work for a trans Indigenous woman, but trans women are nonetheless always the ones doing it.

Touching Maracle’s things made me feel like I was learning so much about how she and I work in similar ways. I was touching the objects that were meaningful to her, but I’ll never know why or how.

I was touched to see Maracle’s artwork Love Potion (ca. 2015). Love Potion was also in a brown paper bag, at the bottom of a box of clothes. It consists of two nipples made from copper wire and covered in red paint. Maracle wore the nipples during her performace Death in the Shadow of the Umbrella at Vancouver’s Queer Arts Festival in 2015. During the performance Maracle said, “Why is it that tedious tomes continue to be churned out by a circle of lesbian/feminist writers, denying, decrying, the conceptual possibility of a transsexual woman?… Oh for the time when our lives matter more than our deaths.” Trans Indigenous women are caught between multiple communities that do not claim them.

When approaching Love Potion, I didn’t want to think about erotics and sexuality, and fall prey to how trans women are often fetishized. I am drawn toward Love Potion because, to me, it is a symbol of the female body for trans Indigenous women. Trans women are made to hate themselves by society and are constantly told that no one will ever love them. For many trans women, access to gender-affirming surgeries could be seen as a love potion: if you can access them, people will love you. For some it could feel impossible to believe that, as trans women, we will ever be loved. I know there are more tender readings of the work. But I’m trying to remember, in my social-justice infected brain, that more than one thing can be true. We can walk a tightrope of desirability politics, and also think through the pressures of what defines us and makes us loveable as trans Indigenous women. And the truth is that trans women feel pressure to get bottom surgery, even if they’re not gender dysphoric. I want to ask: What possibility comes with these nipples? What possibility comes with me giving in to shame and being a shapeshifter? Love Potion makes me reckon with the impossibilities of possibilities that can coexist.

Aiyyana Maracle, Gender Möbius (performance documentation), 1995. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

Aiyyana Maracle, Gender Möbius (performance documentation), 1995. Image courtesy Grunt Gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

I was honoured to go into Maracle’s archive with poet Trish Salah. Salah had a close relationship to Maracle. Along with a note Maracle had written about a show they were doing together, she also wrote about “bringing [trans women] back to life by making art about them.” I realized that I am part of a network, community and family of trans women that spans generations. Maracle made a point of having relationships with trans women—that was her community. And those are the people whose shoulders I came in on. Maracle gave her archive to a legacy of trans women whom she wanted to come find her words and work. Finding Maracle in the archive has been a powerful form of healing and remembrance for many of us. Maracle’s legacy is one of a woman who lived in isolation, poverty and depressive states, who gave everything to Indigenous community arts, and yet who was allowed to fade away from memory—until her daughters came to find her. I am forever grateful for the opportunity to do this work and bring her back, by making art about her.