Until the early 1970s, it wasn’t uncommon for houseplants to be used inside exhibition spaces, as decor. Gene Pittman, a long-time exhibition photographer for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, calls them “a staple,” likening houseplants at the time to the patrons in the gallery, “sometimes aloof and in the background or congregating around the radiator as if in discussion. And then there are those that are really into the work, standing in front of a sculpture’s light, their shadows enveloping the work.”

According to curator and writer Arden Sherman, the houseplant-as-decor disappeared from galleries due, superficially, to conservation concerns and, fundamentally, to the market: “There’s obvious risk to housing organic matter so close to precious works of art, which tend to be susceptible to damage by moisture and insects.” Conceptualism changed the market so much that museums wanted maximum control of the gallery space, now a hyperneutral environment, with sophisticated technologies laced into its pristine surfaces to compensate quickly and quietly for natural disruptions.

Interestingly, the moment of the houseplant’s disappearance in Western art galleries also marks the emergence of Land art or Eco-art, where artists made either projects that could only be seen in situ, forcing the “gallery” outside, or that brought the outside in. In Hans Haacke’s Grass Grows (1969), a mound of earth, slightly taller than the average viewer and covered in grass seedlings, grew into a verdant knoll. The work is widely understood to have materialized the contents of Haacke’s manifesto:

“…make something which experiences, reacts to its environment, changes, is nonstable…make something indeterminate, that always looks different, the shape of which cannot be predicted precisely…make something that cannot ‘perform’ without the assistance of its environment…make something sensitive to light and temperature changes, that is subject to air currents and depends, in its functioning, on the forces of gravity…make something the spectator handles, an object to be played with and thus animated…make something that lives in time and makes the ‘spectator’ experience time…articulate something natural…”

The manifesto now reads as a predictive script not only for Land and Eco-art, but also for movements in the decades that followed: relational aesthetics, performance art and process-based art. There is deep, media-based boredom here (one can only hang from a harness, drunk, angry and drizzling paint on a canvas on the floor for so long); it is no coincidence then that the moment plants were outlawed from galleries as interior design, they were readmitted as potential exhibition objects.

Houseplants are largely unquestioned as a commodity, though they are in fact political—harvested and extracted following colonial patterns, the very same ones, incidentally, that increasingly affect how we understand art.

Of the many forms plants have taken in galleries since the 1970s, it’s the houseplant that feels most prolific now. It’s an intriguing return: something that once belonged in the gallery, and to which we ascribe familiarity and pleasure, can feel estranged in the contemporary gallery when positioned as art. Does the houseplant-as-art provide contrast: a modest attempt to soften the edges of the sterile white cube with literal life? Is there a subtle capitalist complementing (in Frances Stark’s preferred definition of the word: “offsetting mutual lacks”), where the houseplant makes the art easier to envision in a domestic space? Houseplants are largely unquestioned as a commodity, though they are in fact political—harvested and extracted following colonial patterns, the very same ones, incidentally, that increasingly affect how we understand art. There is a fascinating discord between the conceptual justifications for the houseplant’s presence in the art world and how the houseplant, as material, acts as a critique of said art world.

If the houseplant-as-art is a problem, it is in its unacknowledged connection to the supply chain, to nature’s commodification, to people from certain places wanting something from others and figuring out how to bring it home. And the houseplant hides its own problem very well. Every aspect of the contemporary houseplant’s existence—from its seed, to the farm that cultivated it, to wholesale buyers, to plant centres, to the consumer—embodies the flow of both nature and capital. The houseplant is a ghost—a sign of a less commercial, industrial relationship between humans and the natural world, but also produced by those very structures it seems to transcend. It might be the ultimate commodity fetish, because its presence so successfully masks its origins and exchange. It is with this bitter taste that we can consider the most prolific occurrences of the houseplant’s use as medium in contemporary art.

MISE EN SCÈNE

A prop, placed to evoke the domestic or some other identifiable space or scene where one might encounter a houseplant in real life. Its presence is justified by the sum of everything else in the arrangement. This is the case in Liz Magor’s One Bedroom Apartment (1996), in which the contents of an entire apartment are packed and pushed closely together, as they are before the moving truck comes. In Meriç Algün’s A Work of Fiction (2013), sentences the artist has selected from the Oxford English Dictionary are assembled to make a narrative, and it is the home of the imagined author of this cut-up that is rendered in the exhibition.

Abbas Akhavan, Crew (still), 2013. Single-channel video projection, 30 min, looped, no audio. Courtesy the artist.

Abbas Akhavan, Crew (still), 2013. Single-channel video projection, 30 min, looped, no audio. Courtesy the artist.

THE PROTAGONIST

Singled out as the subject, becoming the carrier for a larger idea. Abbas Akhavan’s exhibition “green house” (2013) at Vancouver’s Western Front, for example, contained six things: a large, leafy bird-of-paradise plant, a plaster cast, the residue of a private performance where the gallery wall was scraped with sandpaper, a person on a stool reading aloud from The Natural History of a Garden and two projections. The 30-minute video Crew (2013) follows Akhavan and the curator Jesse Birch as they move the bird-of-paradise first through every recognizable space at Western Front, and then into the private apartments in the building, occupied by senior artists who were (and continue to be) critical to the history of the site. The awkward, effortful transportation of the houseplant enables a fairly comprehensive tour of the public and private spaces that are part and parcel of the history and continued activity of this artist-run centre.

HUMAN-PLANT FRIENDSHIP

A connection, based on the assumption of the plant’s sentience and subjecthood. Practitioners of this trope must know of Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird’s 1973 book The Secret Life of Plants, which documents “controversial experiments that reveal unusual phenomena regarding plants such as plant sentience.” This is textbook stuff for the notion that if you yell expletives at one plant and coo love words at another, the latter will thrive and the former will wither. While these theories were debunked almost immediately upon the book’s release—with botanist Leslie Audus remarking that its claims were so outrageous that it might as well be classified as fiction, and other scientists stating that the studies in the book only represent the authors’ failure to understand or implement the basic principles of the scientific method—the assumption of a possible “deeper” relationship between a human and a plant, beyond subject and object, is something artists and non-artists have long entertained. I received an email recently stating that at a particular art centre, on a particular date, Ray Fenwick would give his performance How to Talk With Plants, which “centres on a person whose starting point is faith in the possibility of communicating with plants.… His belief is tested, and questions begin to pile up, but despite mounting doubts he refuses to lose faith, urging the audience to do the same.” The image in the press release is of a person, mid-speech, with his mouth pressed up to a corded microphone; his face is empathic, and close enough to one of the many plants to bite a leaf off.

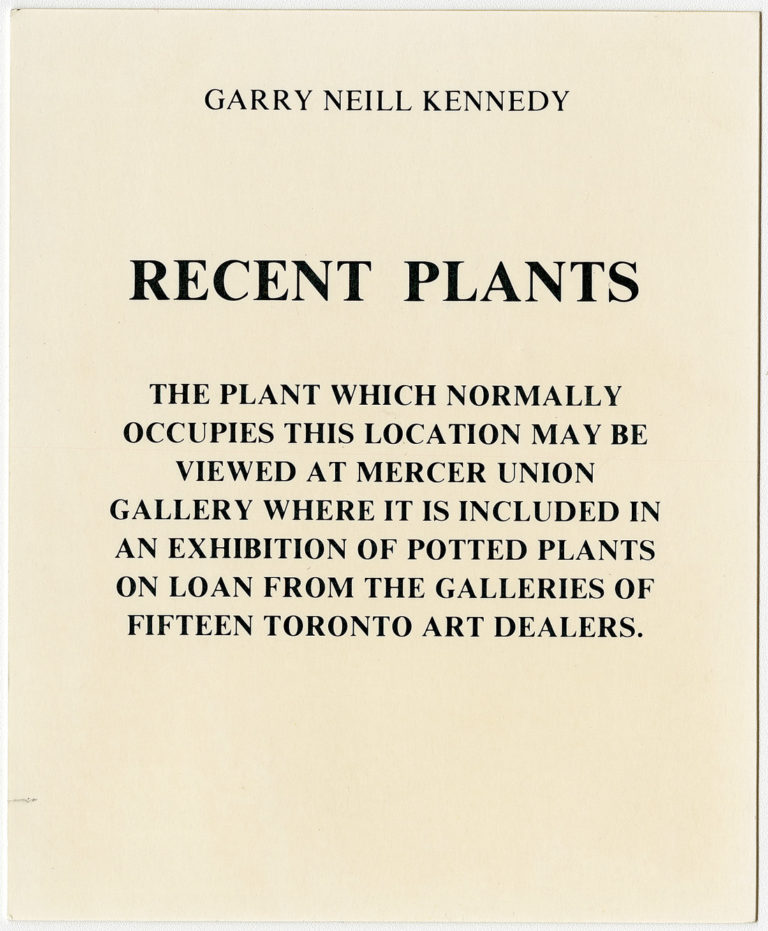

Gallery placard for Garry Neill Kennedy's "Recent Plants" at Mercer Union, September 1980. Courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario, E.P. Taylor and Archives, Special Collections, Mercer Union Fonds.

Gallery placard for Garry Neill Kennedy's "Recent Plants" at Mercer Union, September 1980. Courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario, E.P. Taylor and Archives, Special Collections, Mercer Union Fonds.

Claire Fontaine, Untitled (Feng-Shui Crystals), 2009, installation detail from "Interior Design for Bastards" at T293. Courtesy the artist/T293, Rome. Photo: Danilo Donzelli.

Claire Fontaine, Untitled (Feng-Shui Crystals), 2009, installation detail from "Interior Design for Bastards" at T293. Courtesy the artist/T293, Rome. Photo: Danilo Donzelli.

TALK AMONG YOURSELVES

Rendered social beings, provided a setting in which to talk among themselves. The mass of plants becomes a message. In 1980, Garry Neill Kennedy made an exhibition at Mercer Union where he borrowed one houseplant each from 15 Toronto art dealers, assuring them that the plants would be carefully transported to and from the gallery, be well cared for and exposed to a natural light source. In exchange, each gallerist was given a placard which read: “THE PLANT WHICH NORMALLY OCCUPIES THIS LOCATION MAY BE VIEWED AT MERCER UNION GALLERY WHERE IT IS INCLUDED IN AN EXHIBITION OF POTTED PLANTS ON LOAN FROM THE GALLERIES OF FIFTEEN TORONTO ART DEALERS.” The plants functioned as a wry microcosm of lending practices; they also became stand-ins for their owners, forced to commune and share space in an inherently competitive ecology.

THE IMPOSTER

The poseur, the lazy afterthought, the one who tends to signal that the viewer is in the presence of bad art. In these cases, the plant bears no relationship to what is otherwise happening in the space, and it is here that we find ourselves back at the beginning, in the pre-1970s gallery, in the age of the houseplant as mere decor. To be clear, this is not a tip of the hat to that moment, when the exhibition space was less precious, in terms of being pre-atmospheric, allowing the plant to coexist without assuming its capacity for disruption. Rather, it seems most likely that the artists who deploy plants this way are (knowingly or not) materializing their cumulative visions of Instagram, the platform that simultaneously flourishes at home and in the gallery, subliminally trafficking all kinds of things between the two.

At the moment of my writing, #plants has 17,421,185 entries on Instagram, not to mention the many thousands more filed under #plantgang, #plantsofinstagram, #plantart and so on. In the US, five of the six million people who started gardening in 2016 were aged 18 to 34, which one might assume is the same age range of artists who deploy The Imposter. It’s the ultimate populist readymade and its recurrence suggests that it’s perceived to be an inoffensive, fail-safe addition to any exhibition.

The exhibition text for Claire Fontaine’s “Interior Design for Bastards” (2009) characterizes the relationship between art and design as “close and ambiguous.” Claire Fontaine’s show smirks at this tricky boundary by bringing together objects that underscore the embarrassing earnestness of the DIY interior decorator (for whom the exhibition space of the internet is the only license they need). Included is a table of potted plants with one sickly white orchid, a large wall painting of a Feng Shui compass (diagrammatic of some kind of mindful orientation with other objects in the exhibition, rendered in attractively idiosyncratic colours), a huge red fishing net with crystals dangling from it, and three identical white neon signs, each produced by a different artist, which read: “THIS NEON SIGN WAS MADE BY (…) FOR THE REMUNERATION OF (…) EUROS.” The Imposter, then, is precisely the butt of Claire Fontaine’s joke—a joke whose project it is to muddy the criteria that regulate art and design’s separateness.

Michael Anthony Farley writes that houseplants are among art’s “age-old, lowest-common-denominator motifs.” After encountering them en masse at a 2017 art fair, he “had the sudden impression of an ancient Roman libertine—drunkenly admiring a bathhouse orgy fresco while the Republic burned outside.” Such a reflection is standard fare in the endlessly panelled, existential, rhetorical whirlpool that is the post-Trump art-politics debate. But Farley acknowledges a conceptual impotence that resonates with The Imposter’s affiliation with both the pre-1970s gallery decor plant and so many artists’ utterly uncritical deployment of houseplants. Houseplants had one of their first waves of popularity after the Industrial Revolution, suggesting both their therapeutic and nostalgic, return-to-nature functions. It is hard to look at houseplants, inside or outside the gallery, as a trend, when their dark, ghostly, contradictory nature is so—for lack of a better word—perennial.

Scenocosme, Akousmaflore, 2012. Sensitive and interactive musical plants, dimensions variable. Courtesy Galerie d'art Louise et Reuben Cohen . Photo: Mathieu Léger.

Scenocosme, Akousmaflore, 2012. Sensitive and interactive musical plants, dimensions variable. Courtesy Galerie d'art Louise et Reuben Cohen . Photo: Mathieu Léger.