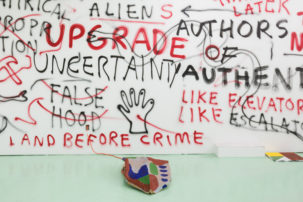

At the entrance of “Devoured by Consumerism,” the late Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick’s first solo exhibition in New York, visitors were greeted by a logo. The brand, which Dick designed to represent the show, depicts two figures in the jaws of a leviathan. One has a television-shaped head and the spiralling eyeballs of someone hypnotized. The other, tumbling head over heels in the maw of the beast, wears a wide grimace—half its face white, with an “X” over one eye, signifying death, and the other half black with a dollar sign obscuring its vision. The image, like the show, left little room for confusion about the intended message: capitalism is swallowing our humanity.

While the logo spoke to the ravenous consumption of globalized markets, Dick’s artworks suggested another possibility, where the spiritual power of the Kwakwaka’wakw devours the machinations of capital. At White Columns, works representing supernatural beings encircled others critiquing mass media, extractive economies and fiat currency. Moving through the gallery counter-clockwise, visitors met two cannibal birds of the Hamatsa dance: Moogums (1985) and Supernatural Raven (1990) crack the skulls of their victims to suck out their brains. Moogums is also known as Galugada’yi (Crooked Beak of Heaven), one of the man-eating birds of Kwakwaka’wakw lore. His round bill forms a hollow circle and his countenance is rendered in striking black, white and red. Supernatural Raven is a spirit known as Gwaxgwakwalanuksiwe’—Raven at the North End of the World. The raven’s face is painted in distinctive Kwakwaka’wakw green. The skulls of his victims dangled from his neck like war trophies. Beyond these two hung two menacing green-and-crimson masks of Bookwus (1980 and 1990), which reference the feral man in the woods who lures human prey into his lair with bewitched food. Bookwus was flanked by the bulbous blue faces Nu-tla-ma and Noohlmahl (1980 and 1992)—the fool dancers who lighten the mood and remind community members to mind their manners at Kwakwaka’wakw winter ceremonies. Beside them were the polygonal masks of forest spirits, Atlakim I, II and III (ca. 1990), their faces painted cream, green, black and red and trimmed with the stripped and dried red cedar bark.

In the centre of the floor were four pieces—two on plinths and two in chairs—that evoked the seats of honour reserved for hereditary chiefs in winter ceremonies. The first, Winalagalis (War Spirit) Puppet (2015), was a carved puppet painted with fearsome green, white and red designs sitting in a folding chair and staring at the static of a television set. In Kwakwaka’wakw lore, Winalagalis, or the War Spirit, is a long-limbed, emaciated man with bloodthirsty eyes. He paddles the earth in an invisible canoe, stirring up trouble wherever he goes. On a plinth beside Winalagalis was Beaver in a Hudson Bay Bag (2019). The teal face of a beaver, carved by Dick’s senior apprentice, Cole Speck, peeks out of a shopping bag branded with the iconic green, red, yellow and black stripes of the Hudson’s Bay Company—an obvious comment on the fur trade and its legacy. Past that, in a glass case, a copper ingot made from melted Canadian pennies is accompanied by a federal document from 2013, authorizing their liquidation: “I am pleased to grant you a licence to use pennies otherwise than as currency,” reads the correspondence on Minister of Finance letterhead. The fourth was Dick’s own wicker chair, from his studio. A cardboard scrap with the lyrics to a song titled “Maker of Monsters” sits in its worn seat:

It’s the maker of monsters

That creeps into your dream

It turns your world around

But it isn’t what it seems

No, it isn’t what it seems

Dick died in 2017. The chair is a moving reminder of the vitality and diversity of his art and how much we lost with his passing. In life, Dick was a monumental figure. “Beau is probably the best West Coast artist since contact,” claims artist and curator Roy Arden in Maker of Monsters, a posthumous documentary on Dick’s life and work.

Dick, a hereditary chief of the Kwakwaka’wakw, was born in Alert Bay, BC, and lived for some time in the remote community of Kingcome Inlet. He began carving as a child and studied under the masters: his grandfather James Dick and father Benjamin Dick, as well as renowned carvers like Henry Hunt, Doug Cranmer, Robert Davidson, Tony Hunt and Bill Reid.

His art was as bold as his character. His Kwakwaka’wakw name was Walas Gwa’yam, meaning “Big Whale.” He was a high-ranking member of the Hamatsa society, which performs a dance about a young man whose rabid appetite for human flesh is tamed through community and ceremony. In his younger years, Dick was a partier. My father, also an artist, came up in the Vancouver scene in the 1980s, when Dick was making a name for himself. Stories abound about a handsome young moustachioed man marching down East Hastings in Vancouver, a freshly carved mask in one hand and a bag of cocaine in the other. But after years of rock-and-roll living, Dick kicked the habit. Like the young man of the Hamatsa dance, he healed. And he became a respected leader among his people, upholding the values enshrined in the potlatch, where to be rich means to give it all away.

In 2008, Dick became the first artist in 50 years to return a set of Atlakima masks, to be danced and burned in ceremony at his home community of Alert Bay—an act of defiance against the economic and ethnographic imperative to collect and preserve. He repeated this cycle in 2012, to dance and burn tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of art back in Kwakwaka’wakw territory. In 2013, during the Idle No More movement, Dick made a copper crest representative of a hereditary chief’s title and wealth. With two of his daughters, Linnea and Geraldine, as well as members of his nation and an entourage of 3,000 activists, he marched the copper to the steps of the provincial capital in Victoria, where he smashed it in protest. In 2014, Dick led a similar pilgrimage to Ottawa alongside Guujaaw Edenshaw, a Haida artist and leader. On Parliament Hill, Dick, Edenshaw and First Nations leaders broke the copper to shame the government for its treatment of Indigenous peoples. “My conscience tells me we have to fight back. And in some ways it is war on another level; nonviolent, but spiritual warfare,” Dick said in Maker of Monsters. “It has to come to that.” Dick planned to host another potlatch in 2017 to dance and burn a third set of Atlakima. He died before he could carry out the act.

Dick was one of the best carvers in the world, but the real power of his work lay in the possibility that he might peel his art off the wall, dance it, burn it, smash it or otherwise assert its Kwakwaka’wakw spiritual value above and beyond its exchange value. On the walls of White Columns—far from the cedar big houses of the Kwakwakwa’wakw—his absence, signified by his empty chair, threatened to defang his art. Some art, like Dick’s, comes to life through action. Death carries the risk of dispossessing his life’s work of this potential. With the communities and movements Dick was committed to stronger than ever, maybe the best thing we can do for his legacy is not to put his work on the gallery wall, but instead to take it off so that it might dance and potlatch and protest and burn once more. This is what Dick lived for.

Today, a new generation of anticolonial and anti-capitalist thinkers in the mould of Dick, like Yellowknives Dene political theorist Glen Coulthard and Kul Wicasa historian Nick Estes, cast Indigenous existence as a life-or-death struggle against imperial and economic domination. Their theses align with the ideas that animated the last decade of Dick’s life. “For Indigenous nations to live, capitalism must die,” writes Coulthard in his book Red Skin, White Masks (2014). “For the earth to live, capitalism must die,” writes Estes, building on Coulthard’s line at the close of Our History is the Future (2019). Indigenous communities and their emergent intellectuals, artists and activists are locked in a deadly dance with the corporations drilling and cutting and mining and extracting from Indigenous lands, and with the colonial governments that back them, denying Indigenous sovereignty. To radicals like Dick, resistance is an existential imperative.

But Dick’s art and life, as well as the Kwakwaka’wakw tradition in which he worked, also points to an inherently complicated interrelationship between colonizer and colonized—the supernatural influence of each over the other, and the power of the wise and spiritual to tame what is ravenous and brutal.

One of Dick’s last works, produced in 2016 and included in the show, was the carved yellow cedar Towkwit Head, wrapped in a black garbage bag, with a painted eye and horsehair brow peeking out from a hole in its crude cover. Towkwit is a feminine spirit who cannot be killed. In ceremony, a Kwakwaka’wakw spiritual leader cuts off her head, sets her on fire, resurrects her and repeats the process over and over again. Towkwit masks are usually wrapped in ochre-stained muslin, but Dick took some obvious liberties to evoke both a trash bin and the process carvers use to keep wood soft and pliable. Dick drew his inspiration for the mask not only from his Kwakwaka’wakw culture but also from a Caravaggio painting of a young David. He intended to carve a mask of Goliath to accompany the Towkwit, but ran out of time. Here, in a half-finished sculptural diptych that holds Kwakwaka’wakw and Biblical traditions in frame, one feels Dick’s work approaching synthesis. “Our whole culture has been shattered,” says Dick in Maker of Monsters. “It’s up to the artists now to pick up the pieces and try and put them together, back where they belong. Yeah, it does become political. It becomes beyond political; it becomes very deep and emotional.”

As we, Indigenous peoples and all peoples, find ourselves in the jaws of man-eating crises, action becomes imperative—in life, as in art. But irony, too, is inevitable. At the back of White Columns, visitors could purchase a Devoured by Consumerism print for $1,000 and a book about the show for $25. Though I would love to put that print on my wall, I don’t have that kind of liquidity, so I settled for the book.

“Beau Dick: Devoured by Consumerism” is a touring exhibition conceived by Beau Dick and LaTiesha Fazakas, and is organized by Fazakas Gallery. It debuted at White Columns, New York, March 16 to May 4, 2019, and is at Remai Modern, Saskatoon, June 21 to September 2, 2019.

Beau Dick, Moogums (detail), 1985. Western red cedar, cedar bark, acrylic. Courtesy White Columns. Photo: Marc Tatti

Beau Dick, Moogums (detail), 1985. Western red cedar, cedar bark, acrylic. Courtesy White Columns. Photo: Marc Tatti