Living in Montreal often feels, for me, like living in two places at once. Geopolitical borders and their ties to nationhood are under constant contest here. The perennial status of the separatist project means that belonging to one nation also entails being present in another not-yet-sanctioned nation that pushes outwards from a shared centre. The city is very cold and also very hot—second only to Moscow in seasonal temperature extremes. It’s French and English. Changing and stagnant. It’s a place both punishing and accommodating, like my tough mother.

Making or showing art in Montreal, by these virtues, is both rewarding and difficult. As in past years, 2016 saw the city continuing to look outside itself in more ways than one, hoping to develop relations to nearby art centres such as New York. At the same time, this outside world revealed an always-present but sometimes-covert hostility, aggressively and outwardly sanctioning fascism and xenophobia. And so, maybe it’s a good time to look back at everything we made while the world around us hardened and we moulded ourselves to its edges.

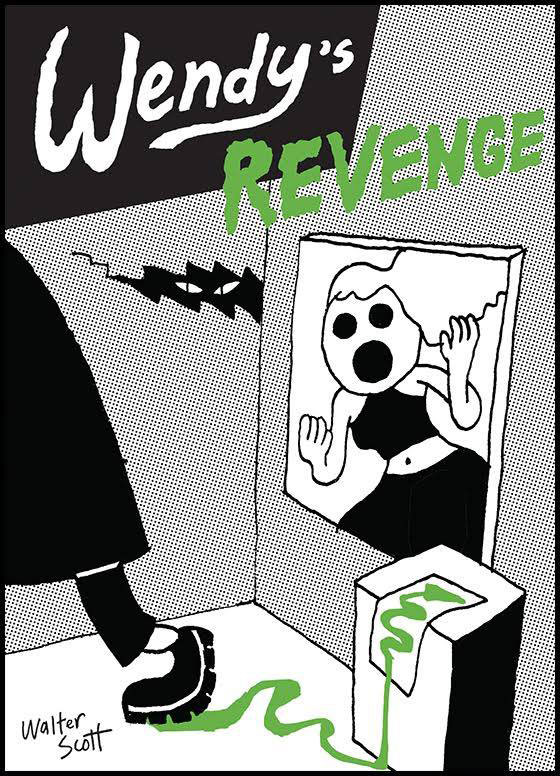

While I was busy navigating this context, Walter Scott’s Wendy was off roving the West Coast, not yet witness to these social changes (or maybe too self-centred to pay them any mind). In Wendy’s Revenge (2016, Koyama Press), Scott’s follow-up to Wendy’s eponymous debut, the titular character experiences a hurricane of micro-aggressions of the kind often faced by feminized individuals. This time around, she chooses to fight back against these, but may need a place to crash while she figures out just how (her buddy, the always reliable Winona, can’t lend a hand, since she’s moved back to the rez).

The cover of Walter Scott’s new book Wendy’s Revenge, published by Koyama Press.

The cover of Walter Scott’s new book Wendy’s Revenge, published by Koyama Press.

Scott’s storytelling is hurried, keeping with the pace of Wendy’s world. Often this means that the politics of privilege slip in, past Wendy, tasking the reader with the uncomfortable but necessary work of reevaluating their distance or proximity to the protagonist.

For this year’s edition of the Biennale de Montréal, “Le Grand Balcon,” Scott produced a series of comics including Let’s Talk About Identity Art, starring Winona, who is pictured winking and throwing up a peace sign in the shared title space. After being continually rejected by a slew of curators and juries, she is finally asked to “make comics about white people,” a choice noted as “a really troubling intervention on the trope of NATIVE STORYTELLER.” By this point, her usually discerning eyes are as hollowed and black as Wendy’s.

Winona is last seen flying out into the vacuum of outer space, leaving the reader to float along in the liminal zone of the final gutter, compelled to pay attention to the kinds of spaces made available to artists whose narratives do not support the project of white Canadian nation-building.

Also on the occasion of the biennial, Frankfurt-based artist Anne Imhof performed her operatic theatre piece Angst III (chapters I and II took place at the Kunsthalle Basel followed by Hamburger Bahnhof). As in previous iterations, Angst was anchored by a series of dancers who worked through exhaustion, performing a careful choreography across a smoky stage that featured a catwalk populated with drones, live birds of prey and Diet Coke. With the dance carrying over to the shared floor space of the gallery, visitors were pulled across the room, repositioned in order to accommodate the actors’ movements—and to get a better view of their disenchanted head-banging or collective shaving with double-edged razors.

The effect was tantamount to attending any one of Montreal’s illicit parties, recently clustered in spaces within the Durocher lofts. The gathering of bodies, the promise of continued action never cutting all the way through consistent boredom or lack of purpose, baited us to endure. (“Let’s stay for another 30 minutes, see what happens,” I whispered in my friend’s ear.) Urgency, another facet of time, is signalled by the contemporaneity of Imhof’s selected props and the dancers’ health-goth costuming—motifs of the present that seem to go out of mode as the performance crawls forward.

A photo posted by Musée d’art contemporain (@macmontreal) on Nov 6, 2015 at 6:10am PST

Between April 2015 and 2016, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal exhibited “l’Oeil et l’Esprit,” the material result of notable Quebec-based artist Geneviève Cadieux’s mining of the 7,800 works held in the museum’s permanent collection. In practice, the show offered a re-ordering of time, pressing an accumulated history into the contemporary moment that Cadieux enters the archive. The present here is haunted by the spectres of a history built by those institutions it relies upon—both the museum the artist was invited into and the collective voice that allows for certain traces to remain, well, traceable.

Speaking on the vanishing nature of queer and post-colonial online resources, Juliana Huxtable has commented that “[a] lot of alternative reference works and information sources disappeared. What I didn’t realize was that this archive was totally ephemeral…. When I couldn’t find the sites that I remembered, I felt I had been wronged.”

What Cadieux’s exhibition did by bringing source materials together via auxiliary connections—finding new ways to link objects that aren’t necessarily linear or historical, aesthetic or rooted in taste—is offer alternative routes to such memory. Messy and unreasonable, her regroupings allowed for new pleasures to take form; objects had enough room eked out between and through them to disclose histories usually passed over by dominant technologies of remembering.

Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik’s The Nightshade Club imagined a dystopian brunch restaurant within Articule in Montreal. Photo courtesy the artist.

Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik’s The Nightshade Club imagined a dystopian brunch restaurant within Articule in Montreal. Photo courtesy the artist.

Montreal’s depressed economic climate is often gruelling, meaning that surviving or staying in business (in one way or another) remains a feat unto itself. Living here, for one, means bearing witness to countless businesses opening, only to close. Sometimes they seem to fold during the very process of going public, continuing to linger deferentially in their crystallized state for weeks, or even months.

For his late-summer exhibition “Nightshade Club” at Articule, Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik opened one such business, installing an erstwhile, forgotten restaurant in the space’s front window. By the time of its finissage, the bistro-turned-exhibit had transformed into a quickened model of entropy: plaster and wires hung from the ceiling, pieces of waffle were strewn and woven through the detritus. Attendees were served fares mirroring the likes of neighbouring brunch-friendly gentrifiers like seasonal compotes and triple-berry fro-yo waffles, brushing off the drywall sure to find its way onto their plates before taking a bite.

Opening a small business without capital as incentive (speaking in financial terms, at least) has nevertheless remained a popular reason to take up space in Montreal, where rent remains relatively cheap. Over the course of the past year alone, a flurry of project spaces have cropped up around the city.

Puppies Puppies, ????, , 2016. Anodized archery arrow, pig’s heart, dimensions variable.

Puppies Puppies, ????, , 2016. Anodized archery arrow, pig’s heart, dimensions variable.

Taking roost in the back third of 820 Plaza, one such locale which opened in 2015, Eli Kerr and Daphné Boxer opened Vie D’Ange early this fall. The two inaugurated the space with an eponymous group exhibition, which brought together works by Julian Garcia, Alan Belcher, Puppies Puppies, Simon Belleau, Andrew Norman Wilson, UV Production House (Brad Troemel and Joshua Citarella) and Kelly Jazvac. In this exhibition, the contaminants of widely relied-upon building materials were centred, forcing our attention toward the imperceptible venues through which petroleum flows and spills (one being the project space itself, a former auto shop).

Cause, effect and the speculative end of days collided here. The results materialized as new mutations in the Real, such as a roaming tortoise-shelled Roomba by Belleau whose only purpose is to clean a mess we can sense we are generating, but can’t see. In Puppies Puppies’ ????,, the popular emoticon is pushed past its virtual matrix, existing as a rotting pig’s heart pierced by a blue arrow. Vie D’Ange imaged a future for those who follow toxicity, sourcing it, mining it, transporting it through authorized pipelines—a space no longer suitable for fragile humans, now populated by angels and hybrid imaginaries.

Loreta Lamargese is a curator and writer based in Montreal. Since 2014, she has been curator at Division Gallery.

This post was clarified on December 14, 2016. The original copy misattributed some quotations to Walter Scott’s Winona character.

Anne Imhof's performance Angst III took place at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal as part of the Biennale de Montréal. Photo: Jonas Leihener via Facebook.

Anne Imhof's performance Angst III took place at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal as part of the Biennale de Montréal. Photo: Jonas Leihener via Facebook.