My year of realizing stuff in Toronto began in May, on a train from Halifax on which I had planned—and failed—to read books I was supposed to have read two years ago or at least to listen to 25 hours of the New Yorker Fiction Podcast (I haven’t finished a novel since 2009). Somewhere in between New Brunswick and Quebec, my phone kept dropping Canadian Art’s call in response to my application for their editorial residency.

When I got to Toronto, I bought a bed frame. Soon after, I took a 33-hour Greyhound ride to Durham, North Carolina, where my childhood best friend was about to finish law at Duke. At the border, a customs guard asked me what I did for a living. “Who pays you to be an art critic? Did you go to school for that?” I can’t remember what I said after I let out a chuckle that I probably shouldn’t have. I definitely remember hesitating to say “kind of?” when he asked if I looked at art to judge it with “yea” or “nay.” “That’s a lot of power you have,” he said. After, I watched a rerun of the Cavaliers versus the Raptors in Cleveland’s Greyhound station at 4 a.m.

Currently, many people are making before-and-after image macros, with an optimistic photo of themselves on the left, captioned “me at the beginning of 2016,” and on the right, a drained, hollow shell of that human, captioned “me at the end of 2016.” My Instagram Explore feed this year consisted almost exclusively of anxiety memes, clips from Keeping Up with the Kardashians, and slime videos. I took selfies with Janelle Monae, Amber Rose and Juliana Huxtable, saw Blood Orange in concert twice, had my natal chart read by GothShakira and Hannah Black, and am blessed with more POC friends than I’ve had in a decade. The following exhibitions in Toronto are highlights of the year for me.

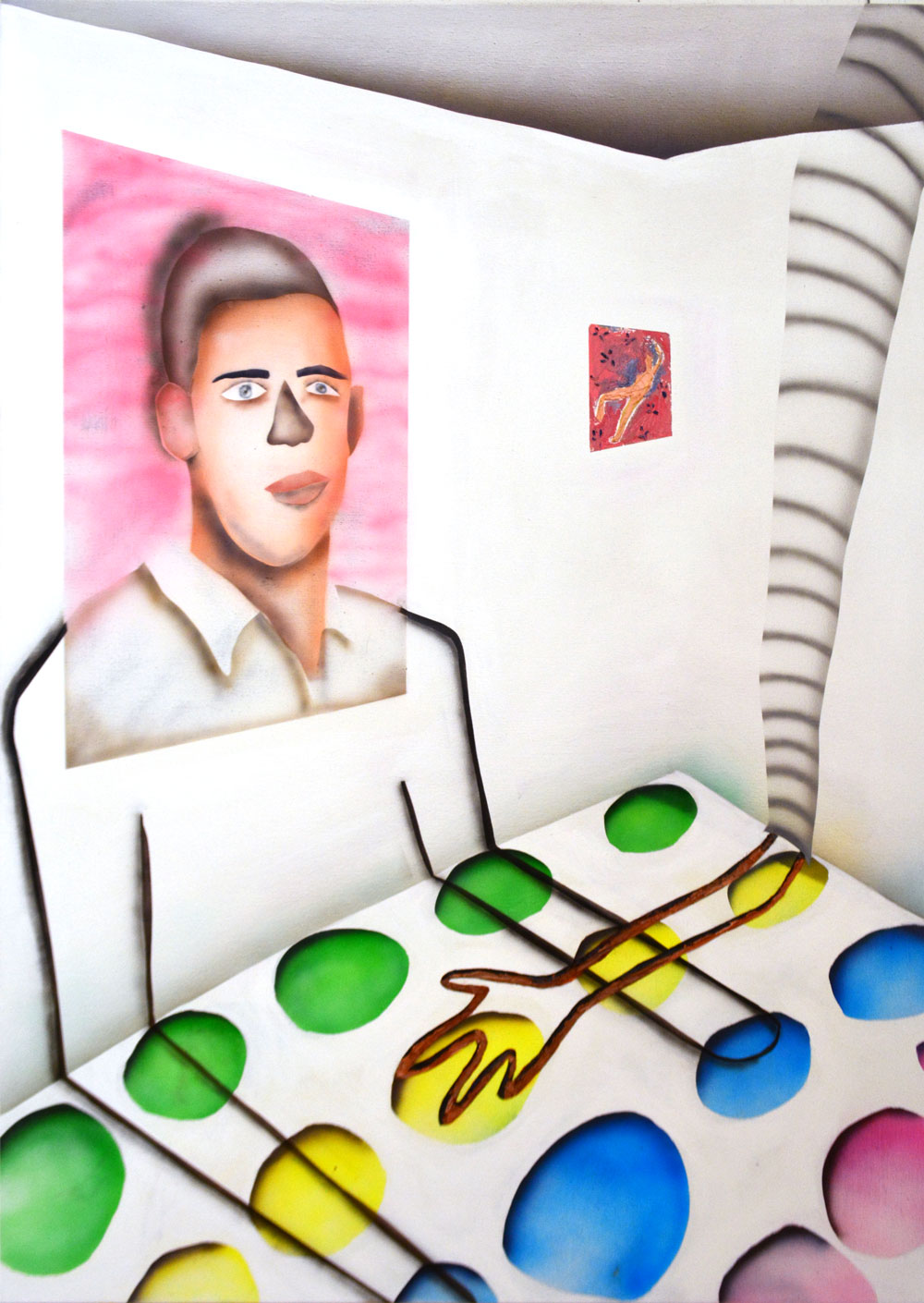

geetha thurairajah, Hotlines, 2016. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 55 x 45 in.

geetha thurairajah, Hotlines, 2016. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 55 x 45 in.

geetha thurairajah’s “GOODBYE HERE NO MATTER WHERE” at 8-11 in March was headlined by Hotlines, her unaffected representation of Drake, whose hybrid identity is famously characterized by his parents: a Jewish mother in Toronto’s posh Forest Hill neighbourhood and an African American father in Memphis, Tennessee, where Drake was told he was “the furthest thing from hood.” In Hotlines and other works, thurairajah attempts to configure nuances of her own hybrid identity, meshing abstracted symbols of a Tamil culture she’s only experienced secondhand—she grew up in a primarily white suburb of southwestern Ontario—with loose pop-culture references. “Being Tamil, there is always an expectation that I should understand this ‘exotic’ side of my heritage, but I don’t,” she says. “I have never been to Sri Lanka; I’ve only explored it on the Internet.” Smaller works, also airbrush paintings based on Photoshop sketches, derived from cliché representations of Tamil culture, especially the swords and the tiger that emblazon the flag of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. thurairajah’s motifs interact with nebulous figures—race-less and gender-less—in ambiguous landscapes that are rendered with sharp, shadowy gradients reminiscent of the surrealism of Giorgio de Chirico. In her paintings, digital devices sometimes float, user-less: a nod to the screens that inspired them, and that will later be windows into their afterlife.

Over the two-week course of thurairajah’s show, Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit announced that there were no grounds to charge the officer who fatally shot Andrew Loku last July. It instigated Black Lives Matter Toronto to set up camp at police headquarters to demand the release of the officer’s name and to cease racist carding. The pressure levelled by the 15-day occupation—in which throngs of protesters clashed with police and endured all manner of precipitation with a profusion of donations from community support—resulted in the coroner’s announcement of an inquest into Loku’s death in mid-April.

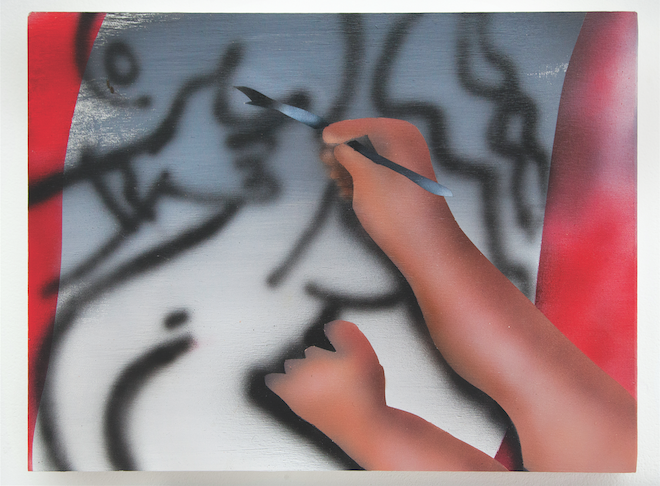

Ambera Wellmann, Wunde, 2015. Oil on wood, 23 x 25 in.

Ambera Wellmann, Wunde, 2015. Oil on wood, 23 x 25 in.

“Clay Pidgeon,” Ambera Wellmann’s mid-August solo show at Dupont Projects, was a set of frigid yet pulsing oil paintings of kitschy porcelain objects, finished with just a few hits of stark white. Sometimes amorphous and sometimes anthropomorphic, the porcelain objects’ misshapen edges suggested the unknowable boundaries of our interiors. Then there’s Wellmann’s Instagram, which caresses her paintings, and where you can find hand-like arrangements of asparagus or snow peas (with fake nails, or attached to sticks, or set to a schmaltzy soundtrack my Shazam can’t identify). The account—almost 8,000 followers strong—primarily testifies to Wellmann’s absurdist, Meret Oppenheim–like use of banal objects to express interior life, particularly perversity. There are recurring motifs: padded bras, through which she contorts her torso, knees or elbows in suggestive poses, or into which she cracks eggs; Trump, whose screaming orange face she juxtaposes with an orange Croc, the opening of which mirrors his mouth; fake French-manicured nails or fingers, swapped with the tips of candles or pickles or hot dogs; thongs, with her elbow or knee bent into them to mimic the crevice of an ass (meme-maker @pablopiqasso poached one of these images and captioned it with “When you’re not brave enough to send your real nudes”).

I first spoke to Montrealer GothShakira in April about the potency and relatability of her personal-is-political, intersectional-feminist memes and their potential effectiveness at critiquing the subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle misogyny and white supremacy she encounters IRL. I met her in the flesh in September at the opening of “What would the community think?” at Xpace, curated by Emily Gove, who says in her curatorial essay that the works in the show confront the prevalence of gentrification to “ask questions about the ways in which those who have access to privilege might use it proactively and mindfully, to engage with issues of displacement and collaborate productively with communities and neighbourhoods.” The GothShakira meme that Gove selected and printed on clear vinyl to respond to her thesis is classic GothShakira: an image of a Latinx pop star—here, Selena Gomez; a verbose narrative caption—here, about the guilt of being complicit in gentrification. Though this meme was thematically on the nose, it occurred to me that a meme is a fish out of water in a gallery, where it meets its unsightly, unseemly death as a curated, ossified object, unable to mutate or circulate.

The proliferation of feminist meme accounts in the wake of the virality of GothShakira and others has made way for multiple, and sometimes obscenely personal, narratives of self-representation that resonated despite this intimacy: consciousness raising 2.0, if you will. I rarely encounter art works in a gallery that are driven by the same urgency and desire for maximum legibility and relatability. The night after the opening of “What would the community think?” GothShakira read my natal chart in the back of an Uber that we split in order to escape a dank martini bar with a poster-sized menu offering a selection of liqueurs and tropical juices any heart could ever desire.

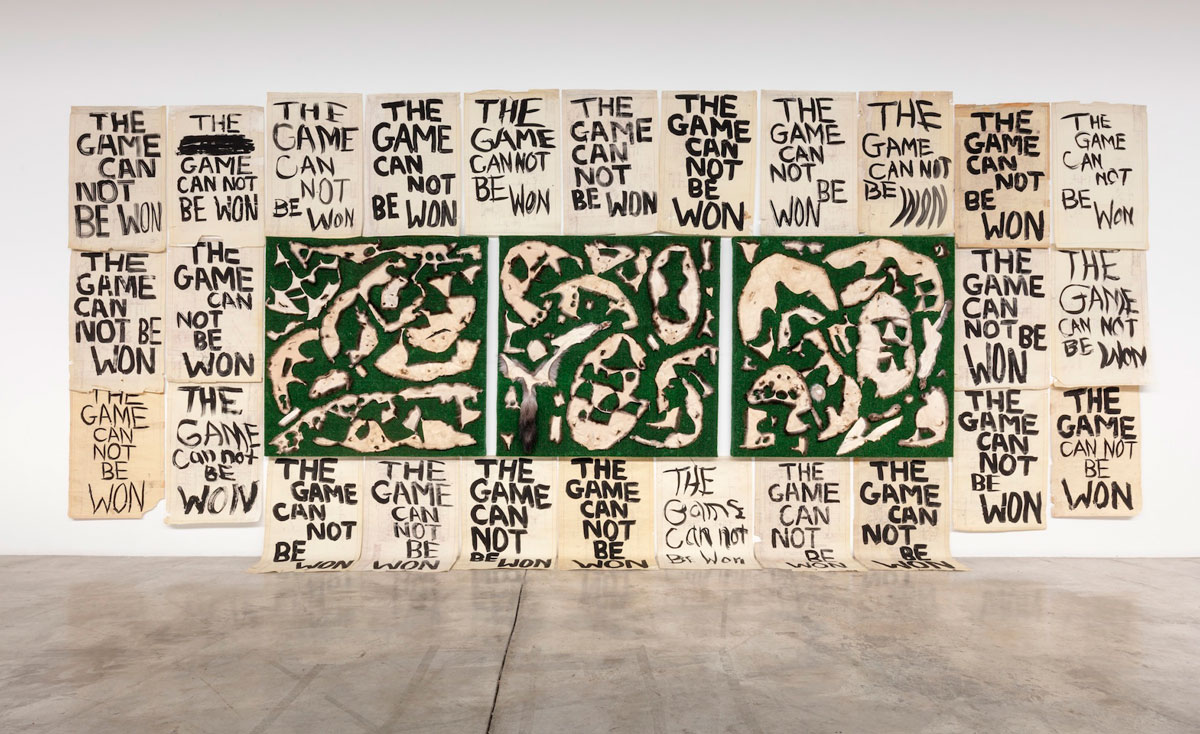

Joseph Tisiga, The Game is Not a Game (26 posters) and An Exercise in Resilience 1, 2, 3, 2016. Installation view. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary.

Joseph Tisiga, The Game is Not a Game (26 posters) and An Exercise in Resilience 1, 2, 3, 2016. Installation view. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary.

Joseph Tisiga’s “IBC: Death Prophecy Denied or Busyness in the Face of Impending Doom” opened in September at Diaz Contemporary, which closed this year. Tisiga’s second solo show there supplemented his signature, coded watercolour paintings of both imagined and lived Indigenous dystopias with an installation that emphatically spoke to the legacy of colonial violence. In The game is not a game, he scrawls “THE GAME CAN NOT BE WON” over 26 residential-school blueprints that frame three central AstroTurf panels blocked out with scraps of furs of multiple animals, salvaged from a kids’ craft workshop. The panel suggests an aerial view of a golf course, invoking recent and ongoing instances of golf courses encroaching on Indigenous land—the most famous being Oka, where rights have still not been returned to the Mohawk, despite the government’s cancellation of the golf-course expansion and purchasing of the land. Most recently, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected Musqueam Indian Band’s bid to force Shaughnessy Golf and Country Club, one of Vancouver’s most elite clubs, to pay residential-level property tax. Thus the game, referring both to the sport and to the bearers of the fur, cannot be won.

In November, Canadian Art brought Wolfgang Tillmans to Canada for the first time in 20 years. Reeling from the US election results, he narrated his photographs with statements to the tune of “sometimes doing nothing is an important component to making work,” and “there are no binaries, black or white, yes or no, in art and in life.” He lost his cigarette as we hugged goodbye after we chatted later. When I opened my purse later that night, I found the cigarette burnt into its lining.