Note to the reader: I am using this regular column to think out loud in public about questions and controversies arising from my current research for a book about contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995.

This column is dedicated, with love and gratitude, to the memory of Jean Fisher.

I have been writing this column for nine months now, and I haven’t yet explained how I define my key term: “Indigenous Art.” At best, I have dropped a few hints. This may seem negligent and irresponsible, but the decision was deliberate. I guessed that my readers and I would all be able to get along well enough assuming we know what Indigenous art is and then, after a suitable period, having only pushed gently at a boundary here or there, I could suggest that, after all, it’s not so obvious.

Is Indigenous art any art made by an Indigenous person? Or is it somehow art that is the product of particular cultural traditions? Or could it be something like: art about Indigenous issues or ideas? And, by the way, what is an Indigenous person?

There are certain words that seem to function most powerfully when we elide their variety of definitions. “Art” is one. I learned about this power when I worked at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Like all large art museums, it is a mediator between very different communities and individuals, all of whom are understood to have a stake in art. These include, of course, the local aristocracy of art patrons, but also academic art historians, curators, contemporary artists and the so-called general public.

Differences are overcome because, we are told, we all love art. If you were to dig deeply, you would likely find that, because we all define that term differently, we do not all actually love the same thing at all. But it is usually socially and economically desirable for everyone involved not to point this out. So the term remains laden with positive value in many quarters, while remaining vaguely defined. I got through a whole art school diploma program and I don’t once remember being offered, or being asked to provide, a definition of art.

Although there are many people who have strong opinions (or legalistic definitions) of the term “Indigenous North Americans,” it is also open to many questions. The most troubling is whether it is a cultural and political identity, or a biological one—that is, a racial identity. Despite the re-emergence of white nationalism into the public discourse in the recent US election, and in European political discussions, race remains a discredited category amongst progressive thinkers. It is the product of politicized 19th-century pseudo-science that attempted to naturalize cultural and political inequalities and differences as biological destiny.

But the ideas of the 19th century show up in the strangest places. In his 1969 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel House Made of Dawn, the Kiowa novelist N. Scott Momaday used the term “blood memory” to explain a character’s ability to reconnect with an Indigenous cultural heritage that had been lost to him.

Anyone who has even briefly studied the history of European racism will recognize this language immediately and understand “blood” as a synonym for shared hereditary characteristics tied to a national culture, which was the foundational idea of German National Socialism and much of the white supremacist thought that preceded it.

Despite this, the term “blood memory” still circulates widely in Indigenous communities, often credited not as a modern invention, but as the traditional wisdom of the elders. It is tragic to have been estranged from your cultural heritage by colonization. It is tragic and pitiably ironic to reach for the very language and concepts of European race theory that were used to justify that dispossession in an attempt to reclaim your heritage. Let’s stop doing that. (I have written at greater length on this subject in the essay “After Authenticity: A Post-Mortem on the Racialized Indian Body,” in the catalogue for Kathleen Ash-Milby’s very interesting exhibition “Hide: Skin as Material and Metaphor.”)

To help see the complexity of potential Indigenous identities, let’s distinguish three things: biological heritage, culture and political affiliation.

As I have already said, I understand biological heritage to mean not a set of racialized traits, but rather the fact that one is a biological descendant of North America’s First Peoples. Ancestry is not inconsequential; many people care about and feel a special connection to their ancestors. I just do not believe that this connection comes with special Indigenous superpowers involving innate knowledge.

The next item, culture, is therefore not the product of a biological essence, but a product of complex circumstances; an intellectual and customary heritage developed out of particular material conditions and interactions with others.

The way in which Indigenous identities have been administered by colonial authorities has often conflated biological heritage, culture and political affiliation.

In the US system, which often relies on blood quantum, Indigenous political affiliation is tied directly to a person’s biological heritage. It is ironic, but not surprising, that the standard for tribal membership in the US tends to be racialized when US citizenship itself is not (recent white-supremacist efforts to the contrary notwithstanding).

Canada, as usual, has found a way to achieve the same effect, but without the racialized language. Federally recognized Indigenous persons have “status”—and that status diminishes into fractions, eventually disappearing for the children of mixed-status and non-status parents.

The effect of both the US and Canadian systems is to ensure that Indigenous communities either practice a kind of selective breeding or shrink away; the latter being, of course, each state’s preferred outcome.

The fact that many Indigenous communities have become the fiercest enforcers of exclusionary membership rules has less to do with maintaining racial or cultural purity (although that rhetoric is put to constant use to justify it) than it does with the divide-and-conquer politics of the reserve/reservation systems.

In the reserve/reservation systems, acting to keep the community small is usually economically beneficial to the existing members. There are many communities that have to share inadequate federal funding—wealth generated, in most cases, by the extraction and exploitation of resources of which we were largely dispossessed by colonization, but which we are expected to beg for and receive as charitable generosity. Occasionally, of late, there is substantial revenue from an economic anomaly like a casino to share, and in these cases, greed for a larger share can also encourage restrictions on community size (and, of course, lure people who had very little to do with the community in the past to seek membership). In short, there are many economic forces working against Indigenous nations imagining membership—and therefore Indigenous identity—in an expansive way.

It may be that some of our historic communities had xenophobic relations with others, but there is a lot of evidence that, in many cases, communities were open to the membership of persons from other groups. I doubt biological race, as such, was an issue until we learned to think that way from people applying categories of race to us.

If we consider these more inclusive ways of thinking about identity related to our traditional notions of hospitality (as abused as they have often been), we might be able to imagine a political future in which our communities and cultural influences are expansive, rather than focused on containment.

Think of all the ways in which people might have a relationship to Indigenous heritages. You might be biologically Indigenous and have federal status, but were adopted at birth and raised by a non-Indigenous family. Or you might be entirely of European or African heritage and be adopted at birth and raised in an Indigenous family. You might be deeply enmeshed in the traditional culture of that community; maybe you even speak the language. Or maybe you are white and married into an Indigenous family, and you have lived your entire adult life amongst Indigenous relatives.

Or maybe you are not Indigenous, but you are interested in all of the fascinating ideas and new (to you) ways of seeing and imagining the world you encounter in Indigenous art. That interest might be appropriative and problematic, but it might also be genuine and well-intentioned. Or it might start out as appropriative and problematic and evolve, with some guidance, into something real and meaningful. Who knows?

We could spend a lot of time, in the tradition of our colonial administrators, making categorical rules for how each of these situations are handled, and who should and should not do what. But I have an easier solution in the form of a simple system. It has three parts: The first is an attitude, and is not quantifiable—that is, despite everything, to maintain a spirit of openness and generosity when at all possible. The second is ethical and has to do with how you describe your relationship to an Indigenous heritage of any sort; all that is required is that you honestly describe what that relationship is and proceed from that position. The third is to make sure that you do not use the knowledge you have about Indigenous culture in a way that works against our common interests or keeps others from speaking for themselves.

You might say, for example, say, “I was raised by non-Indigenous adoptive parents and do not know anything yet about my Indigenous heritage, but I am really curious to learn more.” Nobody could fault that. But that same person could take a less honourable approach and trade on their Indigenous appearance, for example, to claim cultural knowledge or expertise that they do not have. This could be motivated by self-interest, or simply a feeling that, being Indigenous, they “ought” to know. This puts them in a position of bad faith in relation to their own understanding of who they are—which is, in my opinion, a harm to them, but also creates a situation in which someone who might actually have that knowledge and expertise does not have an opportunity to put it to use.

Of course, your relationship to a specific Indigenous heritage will change over time. Ten years on, the person who said, “I was raised by non-Indigenous adoptive parents and do not know anything yet about my Indigenous heritage, but I am really curious to learn more,” might be able to say, “I was raised by non-Indigenous adoptive parents and did not know anything about my Indigenous heritage until I became involved with the Indigenous art community, met some elders and learned x, y and z.” (Well, this person may have learned all sorts of things; let’s imagine it was a lot of brilliant stuff.)

This openness and flexibility gets us beyond a reductive identity politics, and closer to assessing the substance of what people are actually doing and claiming, rather than who they “are.”

Kent Monkman, Miss Chief: Justice of the Piece, 2012. Performance at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. Photo: Katherine Fogden, NMAI.

Kent Monkman, Miss Chief: Justice of the Piece, 2012. Performance at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. Photo: Katherine Fogden, NMAI.

The desire to imagine an expansive sense of Indigenous belonging makes me think of Kent Monkman’s brilliantly subversive 2012 performance Justice of the Piece. Monkman, in the role of his drag alter-ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, sat in judgment of various candidates wanting to join “The Nation of Mischief.” She explained:

…I have decided, contrary to the colonial policies and laws of discrimination, racism and genocide perpetrated by the governments of the United States and Canada—which are designed to shrink the numbers of First Nation, Native American, and Aboriginal people—that I will begin to build a great nation, unbounded by geopolitical borders and blood-quantum laws. The Nation of Mischief.

Each supplicant represents a familiar type of problematic relationship to Indigenous identity or tribal enrollment, including white characters with a romantic fascination for Indigenous culture. As it turns out, however, anyone willing to submit themselves to satiric deconstruction at the hands of Miss Chief is ultimately considered worthy of entrance. She concludes: “In fact, I am going to extend membership to everybody here tonight whose heart is in the right place. Bailiff, you may disperse the membership papers to everyone here who wishes to join my nation.”

How does this all finally pivot around to the questions I began this essay with? I suspect it is obvious by now that, for my book on contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, I will be using an expansive definition of the subject, focusing on the discourse in its entirety and everyone involved in it, whatever their ethnicity. I will also be interested in those artists who wanted to push the boundaries of the category into engagement (or even continuousness) with the wider art world. And I will treat the phenomenon and its various categories as an act of cultural production, rather than as the revelation or return of a repressed essence.

This will allow an opportunity to re-examine one of the pivotal issues of this period—cultural appropriation—and also to look at the work of non-Indigenous allies: artists who made or facilitated work on Indigenous issues, as well as curators and administrators who created opportunities in institutions and also added their own important insights through their practices as writers and curators. In the stories we have been telling ourselves about this period, we have focused a lot on the heroic activities of Indigenous artist-activist-curators to win access to institutional spaces. These are all true, but they do not tell the whole story. Spending time looking closely at our recent history, it is clear that there is another large cast of characters, non-Indigenous artists, writers and curators, who (inevitably, given our initial exclusion) had to open institutional doors in various ways. Some did so reluctantly or paternalistically, perhaps, but others out of a deeply felt commitment that it was the right thing to do. Many learned a lot along the way and taught us things as well.

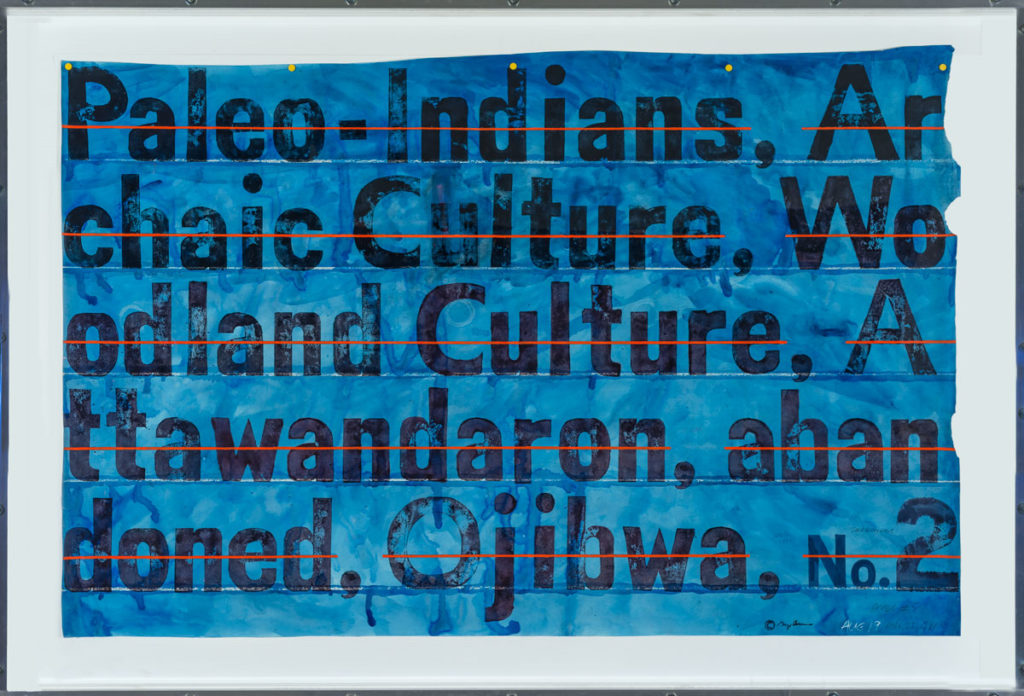

My version of contemporary Indigenous art will therefore include projects like artist Greg Curnoe’s Deeds/Abstracts and Deeds/Nations bookworks (which are so much more than just books). For these, Curnoe researched and documented the history of the land on which his London, Ontario, home and studio were built, and he compiled a list of every Indigenous leader he could find who were signatories to the treaties in the London area. Legal scholars and historians have told me that Curnoe’s compulsive thoroughness meant that they use the latter regularly as a resource. What a marvellous project; how could it not be part of my story?

With all this in mind, I would like to conclude by expressing my respect for one writer and curator in particular, my former PhD supervisor Jean Fisher, who died very recently. Jean was a British writer and academic who lived in New York in the mid 1980s. There, she brought all of her considerable intelligence to the task of helping to create a politicized, critical understanding of contemporary Indigenous art and institutional spaces in the art world it could occupy. In the mid 1980s the discourse desperately needed just those things.

Jean approached Indigenous art with humility about what she did not know, but also genuine curiosity and a fierce sense of justice. She treated the ideas she encountered in Indigenous art and culture as real ideas—ideas robust and lively enough to grapple and contend with, ideas that could change how you understand the world. This, to me, was a sign of the greatest respect; much more so than the mandatory deference so often demanded of white writers now.

The Indigenous art world and the art world in general would have been a considerably lesser place without Jean Fisher. Let’s not forget that.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. If you have advice, information, documents or anything else that might help him with his research on Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, he would be grateful to hear from you: richardhill@ecuad.ca. Thanks to the many people who have already been in touch.

Greg Curnoe,

Deeds #5, August 19-22, 1991, 1991. Stamp pad ink, poster paint, graphite, watercolour on paper, 110 x 168 cm. Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, acquired with funds from the Volunteer Committee to the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the Winnipeg Art Gallery Foundation Inc. Photo: Ernest Mayer.

Greg Curnoe,

Deeds #5, August 19-22, 1991, 1991. Stamp pad ink, poster paint, graphite, watercolour on paper, 110 x 168 cm. Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, acquired with funds from the Volunteer Committee to the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the Winnipeg Art Gallery Foundation Inc. Photo: Ernest Mayer.