Closeness is a conditional invitation in art, where most gallery works come with warnings not to touch and security guards side-eyeing from nearby corners. In the absence of guardianship, anyone raised in the company of other humans knows that art is, unless otherwise stated, eyes-only and from a suitable distance.

In August 2016, Instagram introduced a zoom feature that promised users the ability to “dive into an adorable puppy’s smile,” which no one burdened with a soul has ever prized a zoom for. We want to get closer to things not meant to be seen, or that feel encrypted from a slight distance. In Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, a photographer emerges from his darkroom with evidence of a murder. Instagram offers an opportunity to pinch closer on things that in life would be tactless or salacious to look at. A body part or an unmade bed; a prescription in the deep background, camouflaged by perfume bottles. We’re not looking for murder. We’re looking for vulnerability.

Long before the in-app zoom, artists and personas on Instagram were trying for that kind of closeness themselves—tableaux vivant with flash; faces fraught with anxiety, depression, grief, petulance or sometimes just trails of wet mascara.

On May 10, 2016, artist @audreywollen (25.4K followers) posted an image to her Instagram account: an iPhone next to a white lily, Wollen’s lovely face gazing straight up, slicks of water on the screen standing in for tears. Wollen is best known as the diviner of Sad Girl Theory, one that takes a recognizable archetype and undermines it in execution. The Sad Girl’s forebears can be seen in the likes of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, Manet’s Olympia or Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, which Wollen reprised in her image, only to have it lifted by artist and Instagram thief Richard Prince. Wollen condemned Prince’s use with a screenshot of his post and the caption “portrait of @richardprince4 and his predatory appropriation of naked young girls.”

Pale, sullen sylphs figure heavily throughout Western art history. What differs about the Sad Girl, said Wollen in a 2015 interview with Dazed, is her use of the selfie. “Mediated by tech and the Internet rather than a man with a paintbrush, it still serves a similar function.” By being her own languid muse, gazing into a self-directed lens rather than at the man behind it, Wollen argued, reinterpreting Audre Lorde, that “we can use the products of the patriarchy as tools to dismantle it: the objectification of girls can be re-staged and read differently.”

A photo posted by tragic queen (@audreywollen) on Dec 12, 2014 at 4:47pm PST

Wollen’s images contest, among other things, the anxiety of being a woman in thrall to a male artist, to any male at all, with a measure of aestheticized defensiveness. One post features a broken plate on a piece of paper with the words NO GODS / NO MASTERS struck-through, NO DADS / NO BOYFRIENDS etched below, both a correction and an addition. In her revised Velázquez tableau, Wollen lies nude on an unmade bed with her back to the viewer, watching a tiny glowing version of herself on a nearby laptop. But unlike Velázquez’s Venus, Wollen’s face does not look back at us. That privilege is hers alone.

Being an artist on Instagram is like performing before a two-way mirror: inherently palliative to anxious artists and their anxious audience—shot and viewed alone, engaging through tones and tropes we all become fluent in. I think of Nastassja Kinski’s peepshow booths in Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas—a luminous window into fantasy from the viewer’s side, fibreglass insulation framing a mirror on the other. Flesh in grainy light. A direct, unsmiling countenance. On Instagram, conditions that were previously solitary are now fit to be content. Sadness can be framed as luxury, inaudibly scored by Lana Del Rey. But anxiety shows itself without pleasure, recoiling from what might destroy all that has been carefully built, like the Sad Girl herself. Anxiety deletes its account.

Underneath Wollen’s second-last shot, she wrote an exit speech befitting her role as Tragic Queen: “i’ve grown increasingly unsettled and at times deeply hurt by the climate of online feminism and my own position w/in it. i worry my ideas are eclipsed by my identity as an ‘instagram girl’…‘sad girl theory’ is often understood at its most reductive, instead of as a proposal to open up more spacious discussions abt what activism could look like.” Wollen’s theory (as she imagined it) disappeared after being fed on by the audience she courted. She had no choice but to vacate this iteration of her throne, arguably out of anxiety over what she had created.

“The first known representations of anxiety are found in cave paintings from the Paleolithic era,” writes Allan V. Horwitz in Anxiety: A Short History. “They vividly depict sources of fear—usually dangerous predators such as lions, wolves, and bears—among our primeval ancestors.” For as long as we’ve had feelings—especially the bad ones—we’ve wanted to make art about them, whether that’s on the walls of caves or in lush 17th-century vanitas paintings—skulls and grapes and books poised mid-leaf—a goth Tumblr teen’s feed wrought in oil. As Wollen discovered, it’s not in the Internet’s nature to make art about bad feelings more complex, but it does sometimes write back.

Molly Soda, Phone Zone 2016 Video 13 min 11 sec . Courtesy Annka Kultys Gallery, London.

Molly Soda, Phone Zone 2016 Video 13 min 11 sec . Courtesy Annka Kultys Gallery, London.

In September 2016, Instagram user @scariest_bug_ever (59.8K followers) posted a picture of Natalie Portman, pink-faced and bawling, with the header “when you’re an upper middle class 16–26 year old white woman making selfie art about your hot pale skinny body and someone dares to suggest that what you’re doing might not be the most groundbreaking and earth shattering feminist masterpiece of all time.” While Wollen embodies this meme most precisely, she’s not alone. Instagram is filled with other “girls”—artists and actors and models and writers who have found that a distilled Instagram persona can be good for business. Petra Collins (397K followers), a Canadian photographer who started out capturing lo-fi frames of grimy, pastel babes (including herself) is now shooting Kim Kardashian for the cover of Wonderland Magazine. Frequent Collins muse India Salvor Menuez (46.4K followers), a writer and actor (Transparent; I Love Dick), painter and sculptor Chloe Wise, digital media and video artist Petra Cortright, Molly Soda, Alexandra Marzella and Sybil Prentice (who, like Wollen, also had one of her selfies stolen by Prince) are a selection of other women who fortify their art practices with images from life. It might seem like exotic misdirection, but bio lines often include links to representation—a reminder that for all the intimacy that a bedroom selfie brings, these “Instagram girls” are, first and foremost, professionals.

A photo posted by Amalia’s Instagram (@amaliaulman) on May 31, 2014 at 7:43pm PDT

They’re not all white and skinny, but the trickledown does seem to skew that way, as Argentinian-born artist Amalia Ulman’s durational Instagram performance Excellences & Perfections (2014) implied. Over five months, Ulman produced a long-form, mostly selfie-based narrative of a woman (played by the artist) as she sculpted herself into an ideal Hollywood ingénue. Ulman amassed nearly 90,000 followers over that period, even as, she told the Telegraph, “People started hating me.” Excellences & Perfections spotlighted how deftly false identities can be curated via social media, while throwing into relief the discomfort and hostility that surround women who self-identify not just as sexual or emotional, but as artists.

Scariest Bug Ever, also known as Binny Debbie, is only one of numerous satirical foils to the sad Internet girls that languish in Wollen’s wake, along with Montreal’s @gothshakira (36.3K followers), who filters endless bon mots through her own zodiac-extolling, Latinx identity. Goth Shakira (who goes by Dre in interviews) makes work that pushes against the typically male-focalized domain of memes to spotlight women of colour, and endow them with her own feminist sensibility. Like the Sad Girl ethos, Scariest Bug Ever and Goth Shakira empower through commiseration, but their posts are largely comedic, embedded with their own skepticism of what’s being accomplished.

Theories have a longer shelf life when placed high, something that a platform like Instagram prohibits. There are no guards, no warnings, no scheduled hours for entry. Wollen’s Sad Girl was too accessible, as sad girls usually are. For Wollen, that meant exiling herself from the site, which, in its seemingly uncurated way, is not unlike Ulman’s mapped exit in Excellences & Perfections. The ability to zoom may allow us to get as close to the surface as we want, but what we see there might not satisfy, and certainly won’t resolve until we lift our fingers from the screen.

Naomi Skwarna is a Toronto-based writer and actor. Her work has appeared in the Believer, the Globe and Mail, the Hairpin, Hazlitt, the National Post, Toronto Life, Real Life and elsewhere.

This post is adapted from an article in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Art.

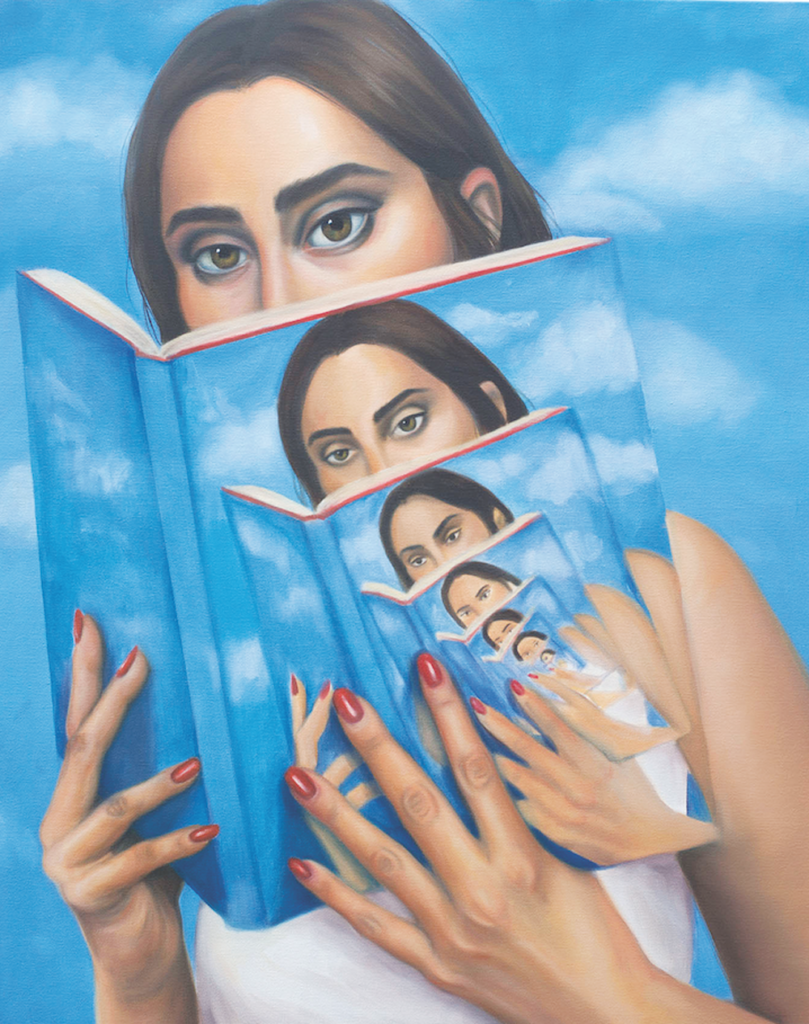

Chloe Wise, A Treachery, 2016. Oil on canvas 76.2 x 61 cm. Courtesy Division Gallery, Montreal

Chloe Wise, A Treachery, 2016. Oil on canvas 76.2 x 61 cm. Courtesy Division Gallery, Montreal