The Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art is a former train station. In its current configuration, however, it has come to resemble a vast cathedral.

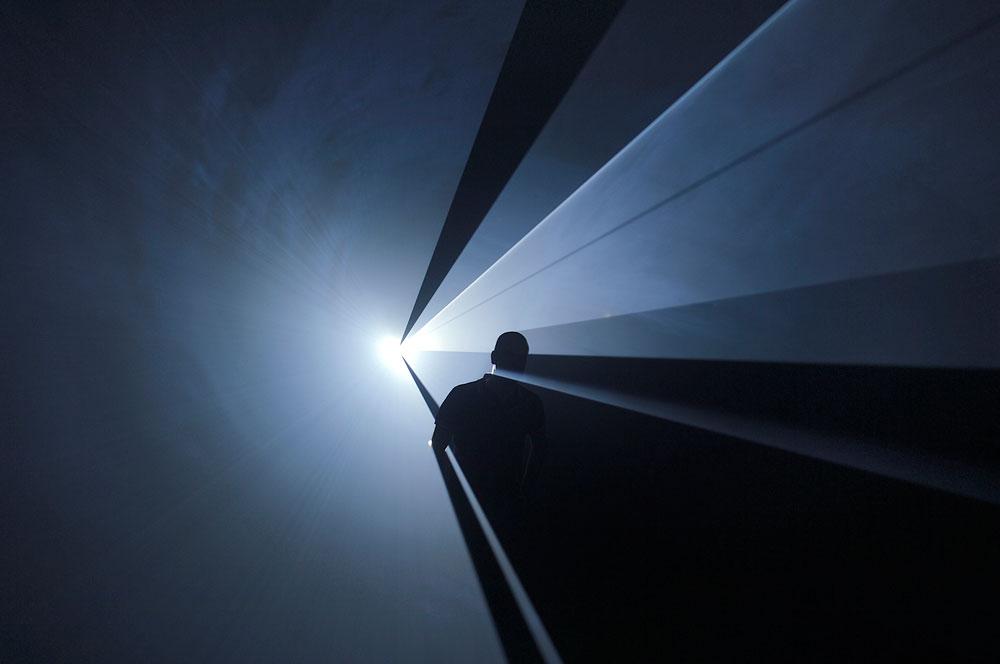

The occasion is an exhibition by New York–based artist Anthony McCall; it focuses on his so-called light sculptures, and its title is appropriately ecstatic: “Five Minutes of Pure Sculpture.” The central hall, a long, wide gallery capped by gothic arches, has been completely walled off from the rest of the museum. The cavernous space is entirely blacked out and filled with a delicate misting of smoke. Out of the hazy, inky blackness emerge vast shafts of light, luminescent conical towers that cast a series of shifting shapes onto the hallway’s floors.

The show’s title is so hubristic, I had difficulty deciding whether or not it’s a joke. For one thing, McCall, who’s been doing this kind of light projection work for some 40 years now (albeit with a 20-year hiatus in the middle), should know well enough that he isn’t creating “pure” sculpture by any stretch of the imagination. These projections are promiscuous hybrids of multiple media, a wild miscegenation of categories.

Furthermore, the idea of any kind of “pure” media, and the desirability of pursuing such a category, hasn’t been in fashion for a long time; it certainly wasn’t in fashion when McCall began doing these light sculptures in the early 1970s. And this lack of material purity is, in fact, a great strength of his work. In a poetically simple gesture, in a single beam of light cutting through a fog of smoke, McCall has collapsed cinema, animation, installation, sculpture and drawing into a single work.

So perhaps this is what the exhibition’s eponymous purity refers to: not the purity of media, nor of material, but the purity of spectacle, the purity of the optical experience. As I wandered through this hallowed hall of the Hamburger Bahnhof, weaving my body in and out of McCall’s walls of light and watching other museum-goers do the same, I briefly entertained the question of what these light sculptures signified—if, in fact, they signified anything beyond themselves. And the deeper I went into the exhibition, the less important that question became. There is so little in art galleries and museums that elicits this kind of visual wonder and delight; the purity of this experience is so rare, and it is, in and of itself, more than enough.