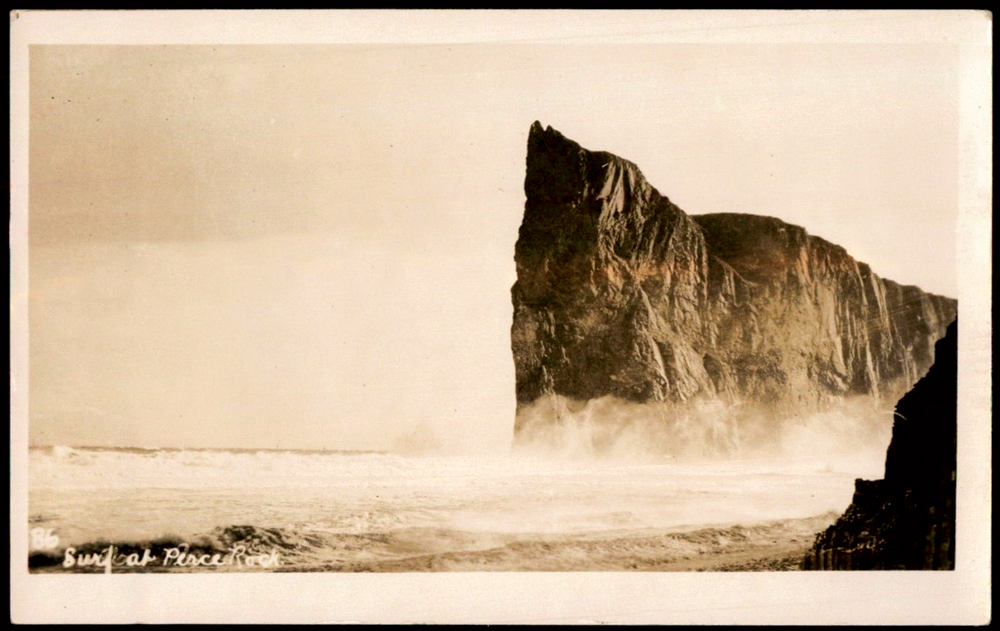

“Surf at Percé Rock” postcard, n.d. H.V. Henderson, West Bathurst, New Brunswick.

“Surf at Percé Rock” postcard, n.d. H.V. Henderson, West Bathurst, New Brunswick.

Percé Rock, the massive limestone formation off the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, has existed for 375 million years, and in 15,000 years it will have completely collapsed into the sea. Water that accumulates in the crevices of the rock freezes each winter, causing hundreds of tonnes of stone to detach annually, and the rhythmic lash of the tides is a constant source of erosion. The impermanence of something so imposing is unnerving. Its existence has spanned countless lifetimes, and yet its longevity is not limitless.

It was this destructive process that inspired French Surrealist André Breton to write Arcanum 17, his meditation on love, war and resurrection, during a journey to Gaspé in 1944. Breton, his wife and their daughter left France in 1941 due to the Nazi occupation, and moved to New York for the duration of the Second World War. Although Breton had escaped the atrocities of Europe, he was personally devastated when his wife subsequently left him and took their only child.

Several years later, while still in the United States, Breton fell in love again, with a woman who had also a suffered terrible personal loss after her only daughter had died from drowning. In their burgeoning relationship, each of them found the optimism to rebuild their shattered lives.

It was the flourish of love born out of terrible loss that Breton projected upon the shifting political landscape of France. “One must go to the depths of human sorrow, discover its strange capacities,” he wrote in Arcanum 17, “in order to salute the similarly limitless gift that makes life worth living.” Just as he had been renewed by love, Breton believed the occupation of France by the Germans would energize the Resistance Movement to regain France’s liberty. In a world fighting off the dark burden of war, he believed that rebellion could be attained through poetry, liberty and love.

While in Gaspé during the fall of 1944, Breton poetically viewed the slow-motion crumbling of Percé Rock as the physical representation of hope in those dark times. It became a powerful symbol of the constant changes he observed in nature, and of metamorphosis itself. “All things, must, on the outside, die, but a power that is not at all supernatural makes death itself the basis for renewal,” he wrote. In the flap of a butterfly’s wings, in the bloom of the rose after winter, Breton found evidence of resurrection. In Arcanum 17, Breton describes nature’s limitless ability to transform, and accounts of Percé Rock are interwoven with folk tales, mythology and the occult.

There is the tale of Melusina, the French spirit who would appear as a woman, but was cursed to transform each week into a figure that was half-woman, half–water serpent. And the story of Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead, who was resurrected by his wife, Isis. And of course the Tarot: the book’s title, Arcanum 17, takes its name from the 17th card of the Tarot’s Major Arcana, also known as The Star. Traditionally, this card depicts a female figure kneeling by a small pool of water with two urns, the contents of which she pours into the water and onto the land to nourish the earth and continue the cycle of life. It is one of the most positive cards in the Tarot deck, and is a symbol of faith in the future.

For Breton, the stories of Melusina, Isis and The Star represented the keys to transforming the world. These female figures demonstrated that, in the darkest of times, there is always a light, and that this light is unquestionably feminine. It was clear to him that only a feminine worldview could remedy the destructive, masculine powers that had brought Earth to a place of such darkness.

“The time has come to value the ideas of woman at the expense of those of man, whose bankruptcy is coming to pass fairly tumultuously today. It is artists, in particular, who must take the responsibility, if only to protest against this scandalous state of affairs, to maximize the importance of everything that stands out in the feminine world view in contrast to the masculine, to build only on woman’s resources,” Breton wrote in Arcanum 17. “Those of us in the arts must pronounce ourselves unequivocally against man and for woman, bring man down from a position of power which, it has been sufficiently demonstrated, he has misused, restore this power to the hands of woman.”

Writing this while on the Gaspé Peninsula (a name that was likely derived from the Mi’kmaq word meaning “land’s end”), Breton, one could imagine, was burdened by the aggressive history of the place itself. It was here in 1534 that Jacques Cartier first planted a cross to claim the land for the king of France, despite the presence of the Indigenous peoples already on it—a moment that marked the beginning of European violence in the region.

This troubling history and the destruction wrought during the Second World War caused Breton to proclaim that artists had an obligation to assist in the transfer of power of men to women. This call was radical: not a declaration for the equal rights of women, but rather an assertion of the superiority of woman over man. Breton believed that women were closer to nature, and therefore feminine values provided the natural forces that were necessary to bring peace and harmony to the planet.

Breton’s coupling of femininity with nature would be challenged 30 years later by Sherry Ortner who wrote, “Woman is not ‘in reality’ any closer to (or further from) nature than man—both have consciousness, both are mortal.”

So perhaps our hope lies not in the divergence of masculine and feminine, but rather in the expansion of our collective consciousness. “Humanity’s aspirations for liberty must always be given the power to recreate themselves endlessly,” Breton wrote. “That’s why it must be thought of not as a state but as a living force bringing about continual progress.”

Jonah Samson lives on Cape Breton Island. His photographic artworks have been exhibited widely and he has produced several artist books, including Yes, Yes, We’re Musicians.

This post is adapted from an article of the same title in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art.