Ruth Cuthand’s travelling retrospective, “BACK TALK (works 1983–2009),” is dense. This extensive show, featuring eight distinct yet overlapping bodies of work, raises questions about “white liberals,” residential schools, academia, religious leaders and other institutions and individuals who might deny that Canada has a history of colonialism. Curator Jen Budney offers this: “For more than 30 years, Ruth Cuthand has been challenging mainstream perspectives on colonialism and the relationships between ‘settlers’ and Natives in a practice marked by political invective, humour, and a deliberate crudeness of style.”

“BACK TALK” filled several of the Mendel Art Gallery’s spaces, but the series Misuse is Abuse (1990) stood out. The title is taken from the governmental stamp on school supplies “magnanimously” distributed to residential-school students; that genteel veneer is dispelled by the words and actions of the so-called educators in Cuthand’s drawings. Several have long nails and maws that suggest the children are to be eaten, not just assimilated. One figure admonishes an Indian doll in a dunce cap with: “Bad bad Indian, Commandment No. 1: Never disappoint a white liberal.” Many of the large, crudely rendered pencil drawings incorporate vulgar clichés; “All they need is discipline” and “Nobody likes an Uppity Indian” are brutal. In response to complaints about her work, Cuthand borrowed titles from the Group of Seven. The “uppity Indian” has a new, supposedly inoffensive title: “January Thaw, Edge of Town.” (Saskatoon has a notorious history of dumping “uppity Indians” at the “edge of town” in winter.)

Cardston, Alberta (1959–1967) (2005–06), like Misuse is Abuse, is biographical in origin, but its language, lifted from the Book of Mormon, is more poetic. The happy family scenes are less visually abrasive, which only emphasizes the outsider status of any who “might not be enticing unto my people, [as] the Lord God did cause a skin of blackness to come upon them” (2 Nephi 5:21). This overlaid golden text contrasts with the image and references racial attitudes from Cuthand’s childhood in a Mormon Alberta community.

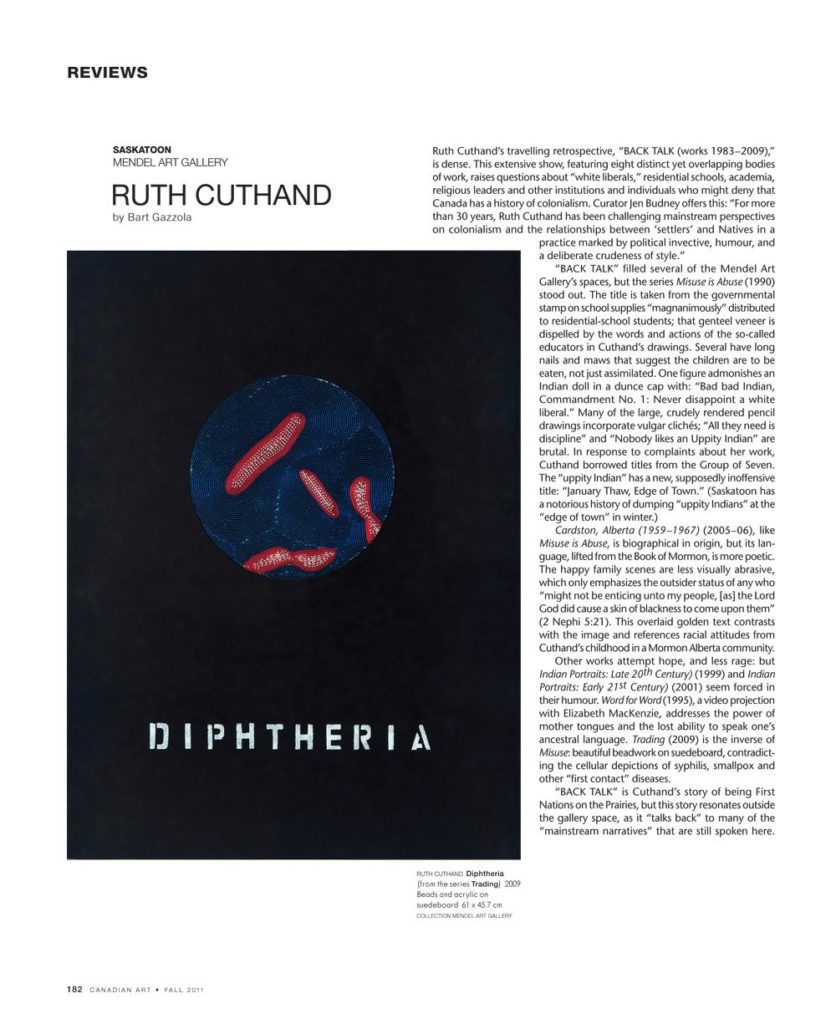

Other works attempt hope, and less rage: but Indian Portraits: Late 20th Century) (1999) and Indian Portraits: Early 21st Century) (2001) seem forced in their humour. Word for Word (1995), a video projection with Elizabeth MacKenzie, addresses the power of mother tongues and the lost ability to speak one’s ancestral language. Trading (2009) is the inverse of Misuse: beautiful beadwork on suedeboard, contradicting the cellular depictions of syphilis, smallpox and other “first contact” diseases.

“BACK TALK” is Cuthand’s story of being First Nations on the Prairies, but this story resonates outside the gallery space, as it “talks back” to many of the “mainstream narratives” that are still spoken here.

This is an article from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.