As I climb up the stairs, a grid of 35 black-and-white photographs appears on an ochre-coloured wall. The photographs, some more recognizable than others, show a First Nations man on the shore, who removes his business suit and walks into the water wearing a bear-claw necklace. He sheds tears throughout the ritual, the meaning of which becomes clearer through his poetic testimony as a residential-school survivor, which is written on a scroll accompanying the pictures. His name is James Nicholas, and he created this work, Taking Off Skins (1994), in collaboration with his wife and photographic artist Sandra Semchuk.

Overwhelmed by the visceral experience of suffering, grief and awakening, I turn around. There, on the far side of the gallery space, against a white wall, I see Rodney Graham’s Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour (2012–13), a triptych of massive chromogenic prints in light boxes stretched from floor to ceiling.

The dramatic contrast of these two works has caught me off guard at the entrance of “Pictures From Here,” which currently occupies the entire second floor of the Vancouver Art Gallery. I expected to be surrounded by lustrous, immersive pictures like Graham’s, not stark and fragmented ones like Taking Off Skins, at this exhibition, which claims to show the “pictures” representative of Vancouver.

Marian Penner Bancroft, spiritland/Octopus Books, Fourth Avenue, 1987. Silver gelatin print. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Marian Penner Bancroft, spiritland/Octopus Books, Fourth Avenue, 1987. Silver gelatin print. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

After all, Vancouver’s reputation as an epicentre of contemporary art owes greatly to local artists like Jeff Wall, who rekindled the interest in representation by introducing “light-box photoconceptualism” and monumental “tableaux” photographs. One of the most broadly recognized aspects of Wall’s artistic style is arguably the sheer sizes and sumptuous outlooks of his photographic prints, which are evocative of history painting or cinema.

The pivotal traits of photoconceptualism converge on the art-historically informed understanding of the photographic surface as a representational space on a par with the pictorial and the cinematic. Thus, the compound word “photoconceptualism” is misleading in its connotation of Conceptual art, which treated photographs as archivable data, rather than the subject of aesthetic experience. Wall himself has publicly expressed his preference for the more inclusive term “pictures” to the vague and outdated nomenclature of photoconceptualism.

Beginning in the late 1970s onwards, the trans-medium approach to photography was shared with other leading figures of the so-called Vancouver School, including Ian Wallace, Christos Dikeakos, Roy Arden, Stan Douglas and Rodney Graham. It is not an overstatement that their work substantially contributed to the international vogue for enlargement and beautification in contemporary art photography, which troubled many critics who saw in it the return of high art that photography had fought against so hard since the 1960s.

Jeff Wall, Monologue, 2013. Chromogenic print. Collection of Andrea and Brian Hill.

Jeff Wall, Monologue, 2013. Chromogenic print. Collection of Andrea and Brian Hill.

The exhibition’s curator, Grant Arnold, butts against the naturalized connection between big, pretty pictures and Vancouver with a sophisticated selection of photographic and video work by 20 artists and artist duos strategically arranged throughout “Pictures From Here.” The show widens the category “pictures” by stretching its chronological and technical boundaries beyond postmodernism and art photography.

This widening is most apparent with the vernacular colour snapshots of Vancouver’s various neighbourhoods taken by Fred Herzog as early (in this show) as 1958. Adhering to the documentary tradition of photography, Herzog’s pictures read in 2017 as the guileless records of a bygone era and its forgotten reality.

Cornelia Wyngaarden and Andrea Fatona’s documentary film Hogan’s Alley (1994) also testifies to a bygone era in a kindred manner. The lo-fi video consists of the interviews with three women who lived and worked in the eponymous community heavily populated by black families and businesses before it was demolished in 1970. With Herzog’s photographs and Hogan’s Alley, viewers engage in the act of witnessing and commemoration with a strong sense of nostalgia.

Fred Herzog, Family on Lawn, 1959. Inkjet print. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Fred Herzog, Family on Lawn, 1959. Inkjet print. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery.

This remembrance is an experience completely dissimilar to viewing a ramshackle house in one of Arden’s large-format chromogenic photographs or the reimagined interior of a 1950s dormitory in Douglas’s two-channel projection Win, Place or Show (1998), shot in luscious, saturated colours. Arden and Douglas, although their works undeniably touch on the history and economy of Vancouver’s Strathcona neighborhood, invite the viewers ultimately to contemplate the pictures themselves, their phenomenological functions and the intellectual rationales behind their scale and beauty.

“Pictures From Here” also attempts to dilute the ingrained preconception about the local artists homogeneously remembered by the mythic attribution to the Vancouver School. To this end, the exhibition pairs the established names with their fairly unknown works either recently acquired by the museum or borrowed from private collectors or the artists. For example, Dikeakos is showcased with 26 Street Scan Photographs (1969–96), his early sequence of 26 black-and-white photographs taken while driving along the south of False Creek, rather than his iconic colour panoramas. Wallace’s large photo-paintings are balanced with a small, black-and-white photograph Disaster (June 17, 1958) (1985), which was originally shot when he was 14 and shows the collapsed spans of the original Second Narrows Bridge. In the same imagistic vein, two large yet rather somber photographs by Wall are on view: a silver gelatin print War Game (2007) and a chromogenic print titled Monologue (2013), the latter of which has never put on display in Vancouver before.

Stan Douglas, Win, Place or Show, 1998–99. Two-channel video projection with four-channel soundtrack. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Stan Douglas, Win, Place or Show, 1998–99. Two-channel video projection with four-channel soundtrack. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Wall’s larger works do not explicitly quote Vancouver—it was a risk to include them, especially given Wall’s numerous famed light boxes featuring local surroundings. Although the show presents the light-box display as an important component of Vancouver’s lens-based art, it does so by including less canonical examples: the modest-sized landscapes of industrial sites by N.E. Thing Co. and the humorous seasonal scenes, each interrupted by a flying frozen salmon, of Barrie Jones.

The light-box works by N.E. Thing Co. and Jones are notably different from the well-groomed, theatrical scenes orchestrated in the cinematic photographs by Wall or Graham. In the latter, the immense light boxes are often discussed in relation to Minimalist sculpture and narrative painting. By contrast, N.E. Thing Co. and Jones tend to reference the moments and places arrested in the photographs—the photograph of elevated business signs taken by N.E. Thing Co. at Boundary Road and Grandview Highway, in particular, is a reminder of the commercial provenance of the light-box apparatus, creating an ironic tension in the rarefied gallery setting.

Throughout, the exhibition portrays Vancouver’s artistic community as an archipelago that harbours many different views. “Pictures From Here” pays attention to the spirit of experimentalism that has existed in the region since the 1970s among artists outside the herd of photoconceptualists. Marian Penner Bancroft’s gritty black-and-white pictures exemplify her enduring interests in the emotional labour and tactility involved in the production and experience of photography. Her pictures, always fragmented, juxtaposed and overlapped, offer an effective counterargument against the seamlessly glistening surface of the tableau photographs included in the show.

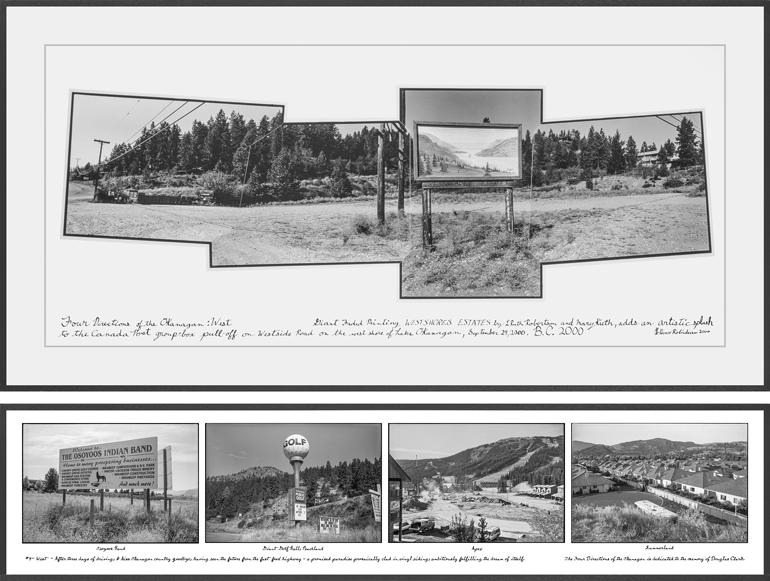

Henri Robideau, Four Directions of the Okanagan: West, 2000. Silver gelatin prints, ink. Collection of the artist.

Henri Robideau, Four Directions of the Okanagan: West, 2000. Silver gelatin prints, ink. Collection of the artist.

Patchworks and fractures are also crucial to Henri Robideau, who stitches discrete photographs together manually or digitally and scribbles his comments around them. Arni Haraldsson uses affiliated tactics in Nothing Will Have Taken Place But the Place (1986), which surveys two different buildings—the artist’s dwelling and the museum—through paired photographs.

Significantly, the exhibition makes sure that these variegated perspectives address Vancouver’s multifarious and contested identity, be it political, economic, cultural or historical. Bancroft’s spiritland/Octopus Books, Fourth Avenue (1987) and Robideau’s Oppenheimer Park Homeless Summer 2014 (2015) or Giant Sparrows & Olympic Village (2015) offer cautionary tales about the gentrification of the city and its unaffordable housing market. Bancroft and Robideau also address the threatened knowledge about the Indigenous presence in the province in Xa:ytem, formerly HOLDING (property) (1991) and the Four Directions of the Okanagan series (2000), respectively.

These issues around gentrification, Indigeneity and contested civic identity resonate more loudly than ever before in Vancouver. One work that drives this home is Paul Wong’s single-channel video Vigil 5.4 (2010), a non-linear documentation of Rebecca Belmore’s work Vigil, which was performed in a back alley in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver in 2002. The powerful performance commemorates the murdered and missing Indigenous women from the city’s streets, particularly those killed by Robert Pickton. Their names are written on Belmore’s arms and cried out loud one by one as she destroys long-stemmed roses with her teeth. Belmore hammers nails, each one representing a victim, into her red dress, leaving it hanging on a telephone pole like blood-soaked skin.

Ian Wallace, At the Crosswalk VII, 2011. Chromogenic print, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Ian Wallace, At the Crosswalk VII, 2011. Chromogenic print, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

On my way out of “Pictures From Here,” I return to the spot where Nicholas and Semchuk’s Taking Off Skins confronts Graham’s Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour, and I notice another discrepancy. Whereas Nicholas tries to remove the mask of a false identity forced upon him by colonialism, Graham wears the fictional character of a resting paddler. The artists’ divergent understandings of identity and masquerade undoubtedly resulted in the drastic formal contrast between their works: the fractured and muddy photographs taken by Semchuk without looking into the viewfinder and Graham’s smoothly sutured tableau brimming with vibrant details.

The skin exposed by Nicholas, Semchuk and Belmore couldn’t be further from the glossy pellicle of grand photographic prints in the works like Graham’s. And yet all of the artworks in “Pictures From Here” respond, either consciously or unwittingly, to the premise that pictures function as the second skin through which a person encounters reality. Whether one aims to lacerate or embellish that membrane, pictures remain the primary visual interface of our image-saturated life. “Pictures From Here” highlights the wild variety of that interface, which moulds the beholder’s experience into heterogeneous conceptions of Vancouver.

Anton Lee is a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia. “Pictures From Here” continues at the Vancouver Art Gallery until September 4, 2017.