Sarah Cale, Idle Ecstasy, 2016. Painting fragments and oil on panel. Private collection.

Sarah Cale, Idle Ecstasy, 2016. Painting fragments and oil on panel. Private collection.

The Vancouver Art Gallery has taken a curiously divided approach to exhibiting paintings over the course of 2017.

“Ambivalent Pleasures,” displayed in the first half of the year, was staked as the first in what will be an ongoing series of triennials (dubbed “Vancouver Special”) designed to showcase the breadth of art production in the city.

Surprisingly, the triennial’s curators Daina Augaitis and Jesse McKee elected to challenge Vancouver’s anti-material art canon by foregrounding painting, among other practices.

This emphasis did not come without some self-flagellation on the curators’ part, however. Both in their choice of title and at public events, they implied that there was a certain irresponsibility in the pursuit of aestheticism during a time of unprecedented geopolitical turbulence—particularly in Vancouver, where art is part-and-parcel of the real estate industry’s erasure of low-income populations. And yet, the exhibition was staged all the same.

Sandra Meigs, pile by furnace from The Basement Pile series , 2013. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery.

Sandra Meigs, pile by furnace from The Basement Pile series , 2013. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery.

By contrast, “Entangled: Two Views on Contemporary Canadian Painting,” the gallery’s principal fall exhibition, on until January 1, takes a considerably more sympathetic approach. In it, curators David MacWilliam and Bruce Grenville have attempted to provide an outline of two trends within Canadian painting: “Art as Idea as Painting” and “Performative Painting.”

In the process, the curators of “Entangled” engage with many prominent painters who have been isolated by regionalist trends and tastes—and such an effort bespeaks a gradually warming attitude toward painting in a city where painterly practice has otherwise been little championed in art education or artist-run centres over the past half-century.

Further, the exhibition of non-local Canadian painters in “Entangled” is significant in a nation where artists have often been more likely to seek inspiration from across the border than from their own compatriots.

“Art as Idea as Painting” focuses primarily on established conceptual painters, such as Garry Neill Kennedy, Francine Savard and Ron Terada, while “Performative Painting” embraces the process-based practices of artists like Rebecca Brewer, Marvin Luvualu Antonio and Nathalie Thibault.

In all, 31 artists are represented. Small assortments of each artist’s work, along with selections from the gallery’s permanent collection, create a framework which is less dialogic and more demonstrative. Here are the artists: this is what they make.

Jeremy Hof, Fluorescent Ring on Purple, 2014. Acrylic on panel. Collection of Keith Ebert. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Jeremy Hof, Fluorescent Ring on Purple, 2014. Acrylic on panel. Collection of Keith Ebert. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

As an avowed painter myself, I have spent years seized by the paroxysms of woe that come with the thought of reconciling my practice with critical circles, and the itinerant tone of distaste with which such groups treat material objects.

It is relieving, then, to see the Vancouver Art Gallery recognize the reality that painting is a preferred mode of production for many contemporary artists and has been so for the past several decades—regardless of what some vocal critics may declare.

Furthermore, the exhibition avoids the arch notes of moralizing with which painters are frequently presented to the public.

Rather than regurgitating cliches about painting’s heroic adaptability in spite of the “adversity” it faces—and in the process of doing so, reinforcing the presumption that painters are effete reactionaries—or, possibly worse, indulging trite notions about painting’s “timelessness” and “life,” MacWilliam and Grenville instead take a more particular, light-handed approach. They convey the specific social and historical contexts from which these artists have emerged via simple presentation. A short didactic offsets the entrance to the show; everywhere else, summary texts are highly limited, if they are present at all.

Blissfully, for this viewer, the curators have provided every artist with the choice of speaking for themselves, through the use of an app; visitors may listen to the artist discuss their process, and learn about the literature that inspires them. Copies of their chosen texts are available for visitors to peruse.

Providing artists with the agency to speak for themselves countervails the drive toward “relevancy” that curation cannot help but introduce to an artist’s work, and it opens up other avenues of interpretation. For Canadian painters in particular, such a gesture allows the work to return into the world of the individual artist, thereby mitigating the threat of overt historicization.

Jeanie Riddle, Category → 1979 (detail, from the installation In A Time of Deep Nostalgia), 2017. Metal, wood, adhesive, latex paint, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Jeanie Riddle, Category → 1979 (detail, from the installation In A Time of Deep Nostalgia), 2017. Metal, wood, adhesive, latex paint, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

There are some obvious criticisms of “Entangled” that will not be explored in further depth in this review, but are worth noting: namely, that some of the artists could easily be placed in either of the two categories on offer; that almost every artist in the show works with non-objective painting methods, though neither of the two categories is eminently defined by these methods; and that the vast majority of the artists in the show are white.

But if a more nuanced criticism may be made of the exhibition’s two themes, it is that they aren’t only different views on painting; they are predicated on entirely different ways of understanding painting.

One might say, for instance, that painting as concept has little to do with painting itself (i.e., if painting is the vehicle via which an idea is realized, why insist on looking at it only as a painting?).

Meanwhile, painting as performance has less to do with performance and more to do with the properties of paint itself (i.e., all painting is a performance in some way, insofar as painters cannot help but be influenced by the gaze of their unseen audiences).

So: In art as idea as painting, painting is a relatively small part of the formula, and in performative painting, painting is a very large part of the formula. Thus, the exhibition is divided in the extent to which the very pretext of painting informs the way in which a work is both realized and interpreted.

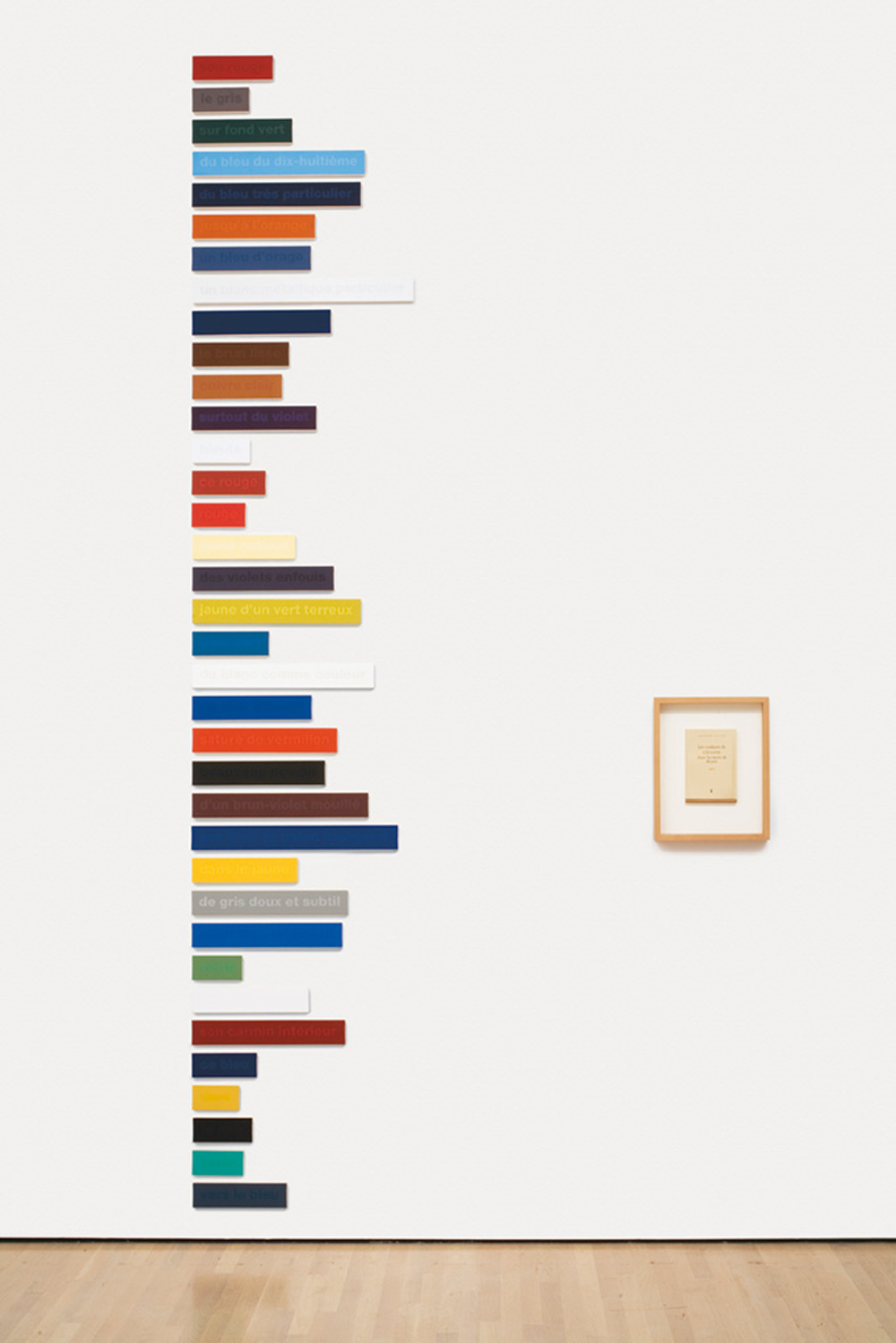

Francine Savard, Les Couleurs de Cézanne dans les mots de Rilke 36/100 – Essai, 1998. Vinylic and acrylic paints on canvas, mounted on high density fibreboard and framed book. Collection Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Francine Savard, Les Couleurs de Cézanne dans les mots de Rilke 36/100 – Essai, 1998. Vinylic and acrylic paints on canvas, mounted on high density fibreboard and framed book. Collection Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

These categories are not intrinsically futile ways of interpreting painting. At the risk of generalizing, it may be said that the artists in one of these categories perceive painting to be purely instrumental toward a determinate outcome, while the artists in the other do not have a determinate outcome in mind at all.

But I struggle to determine if and how these strategies connect, because they do not speak to each other—their only connection is the medium. And perhaps that is the point. To unite these differing approaches under one roof is to suggest that they do cohere in some way—and coherency could be the vector through which disparate data achieve painting’s great bugaboo, “relevance.” (Due to painting’s historical baggage, it is nigh-on impossible for curators to attempt to conceive of it without deferring to the movement model, which attempts to make sense of painting within a social context—regardless of how disinterested a painter may actually be in these movements.)

Indeed, the suggestion of coherency where there is truly none is a distinct facet of Canadian identity. It makes perfect sense that Canadian contemporary painting would be examined through a semi-notional coherency.

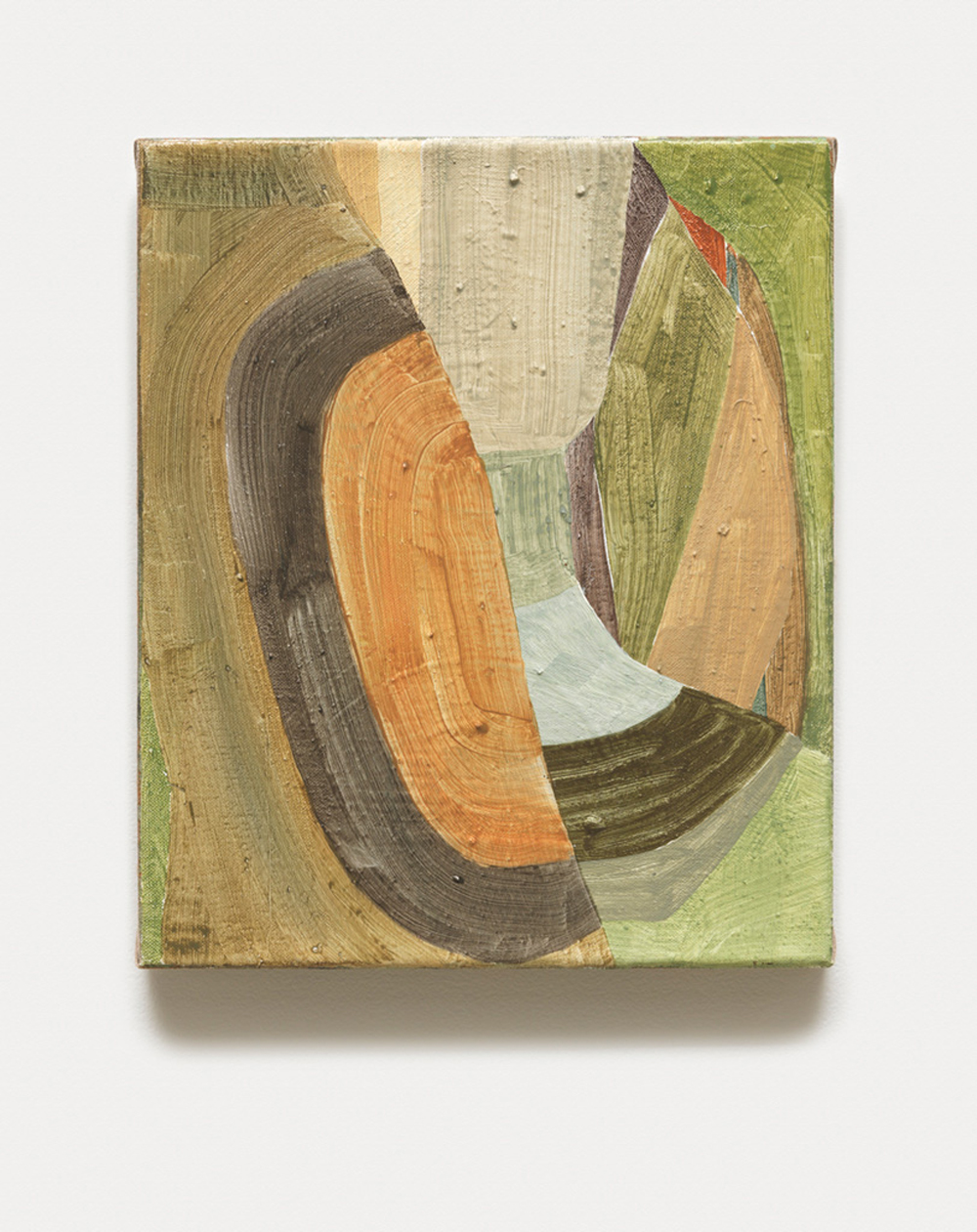

Stephanie Aitken, Calypso, 2012. Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

Stephanie Aitken, Calypso, 2012. Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

It is prudent to mention that “Entangled” at least partly originates in a symposium conceived of by MacWilliam and a cohort of other mature painters active throughout Vancouver, all of whom have taught at local art schools, and who visit with each other to discuss painting frequently.

The symposium, entitled A Crimp in the Fabric: Situating Painting Today, accompanied the opening of the exhibition, and it brought together many of the painters in “Entangled” along with other local artists who incorporate painting into their practices.

Yet these voices were somewhat flattened by the keynote lecture delivered by neo-Marxist critic Isabelle Graw, whose antagonism (as I see it) towards painting set the tone for the rest of the symposium—as well as, in some ways, the rest of the exhibition.

In her keynote (versions of which she has previously delivered elsewhere in recent years), Graw systematically argued that the “value” of painting today results only from its unusual status as a fetish commodity. She also argues that the various discourses which surround painting, critical or otherwise, serve merely to obscure the injustice that they some way participate in.

Guy Pellerin, No. 447 – Maine, Mardi 2 Juin 2015, 18h 02, 2015. Acrylic and graphite on cotton canvas and linden frame. Courtesy of TD Bank Group.

Guy Pellerin, No. 447 – Maine, Mardi 2 Juin 2015, 18h 02, 2015. Acrylic and graphite on cotton canvas and linden frame. Courtesy of TD Bank Group.

I cannot help but think about Graw’s comments when I try to think about “Entangled.”

This is not because of Graw’s argument in and of itself—her views have been widely articulated by other critics—but because “Entangled”’s organizers voluntarily chose Graw to keynote a symposium which was presumably intended to complement the exhibition (even if it was intended to “complement” by critiquing, it need not have included outright malice).

Paradoxically, such a decision echoes the same ethos found in “Ambivalent Pleasures”: that painting in some way ought to be reconciled with the impositions of critics; or, in other words, that painting ought to cohere with some kind of criterion.

Yet “Entangled”’s final selection and display of paintings is decidedly more agnostic on the question of relevance; individual works on the ideational side of the exhibition, such as Tammi Campbell’s wrapped paintings, refer to social networks or systems of production, but they do not collectively propose any single argument—meanwhile, artworks on the process side eschew didacticism altogether.

John Kissick, burning the houses of cool man, yeah No.5 (hang the DJ), 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Katzman Contemporary.

John Kissick, burning the houses of cool man, yeah No.5 (hang the DJ), 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Katzman Contemporary.

As such, the exhibition “Entangled” embraces a kind of proactive ambivalence unto itself. In both the discursive world at large and in contemporary painting exhibitions in particular, the pressure to remonstrate, reconcile, apologize or classify is inescapable; and the compulsion to make marks on surfaces, whether in the service of realizing an idea or for its own sake, abides regardless.

A series of statuesque, weighted abstractions by Montreal-based artist John Heward are suspended and draped across the floors of this exhibition at its halfway point, where its two themes meet. Via “Entangled”’s accompanying app, Heward responds tersely to the query of what inspires him in a seven-second-long clip, citing the last line of W.H. Auden’s poem “The Cave of Making”:

“Here, silence is turned into objects.”

Rhys Edwards is an artist, curator and critic based in Vancouver. His works explore anti-representation through classical painting techniques.