Iconic Canadian artist Alex Colville passed away yesterday at his home in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Colville was 92, with a career that spanned seven decades. Today, many are reacting to the loss and reflecting on his life and legacy.

The “consistency and intelligence” of Colville’s work, as well as a sense of mystery, was what set him apart, says National Gallery of Canada Canadian art curator Charles Hill. “I think it’s the loss of a great talent,” Hill says, describing him as “part of an Atlantic realist tradition that goes back to Miller Brittain.”

Hill also noted a strong sense of “restrained emotion” as being a defining aspect of Colville’s art. “People are very internalized in his work,” Hill says. “In his works, people exist in themselves, and I think that reflects his own personality.”

Indeed, Colville wasn’t afraid to reject trends and remain true to his own internal vision. When abstraction became the rage in the 1950s, Colville continued to work in representation and figuration. And when painting itself fell out of favour in the 1960s and 1970s, Colville continued to create meticulous canvases, many of which have become “classics of Canadian art,” Hill says.

In this respect, Hill says, Colville can be considered in tandem with late Canadian artists Jean-Paul Lemieux and William Kurelek. “They are all very different types of artists, but they all held to their own views in terms of fashion,” Hill says.

Hill also says a sense of “post-war angst” seems to have had an impact on all three. “Colville was a soldier in the Second World War, and I’m sure that marked him,” Hill says.

Taking Simple Subjects and Making Them Profound

After returning from his tour as a war artist, Colville became a teacher at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, where he taught from 1946 to 1963. There, he influenced Christopher Pratt, Mary Pratt and Tom Forrestall, among other nationally respected realist painters who have continued his legacy.

“What was important to me was the way he lived and his ability to take very simple objects and make them profound,” Mary Pratt says. “What I learned from Alex was that you didn’t have to go all over the place and look for a subject; you could just open your eyes and the world could come to you, and you could find it profound enough and worthy of respect and consideration.”

After graduation, Colville became a mentor to Pratt and others.

“He showed me you could just look at the world in its wonderful simplicity and find in that simplicity lots and lots to think about,” Pratt says.

Today, Colville’s influence remains present on the Mount Allison University campus. Two of his major mural works are there, and students come into the university’s Owens Art Gallery each year to look at Colville’s preparatory drawings for the mural, which are part of the collection, says Owens conservator Jane Tisdale.

“He is legendary here at the university,” she says.

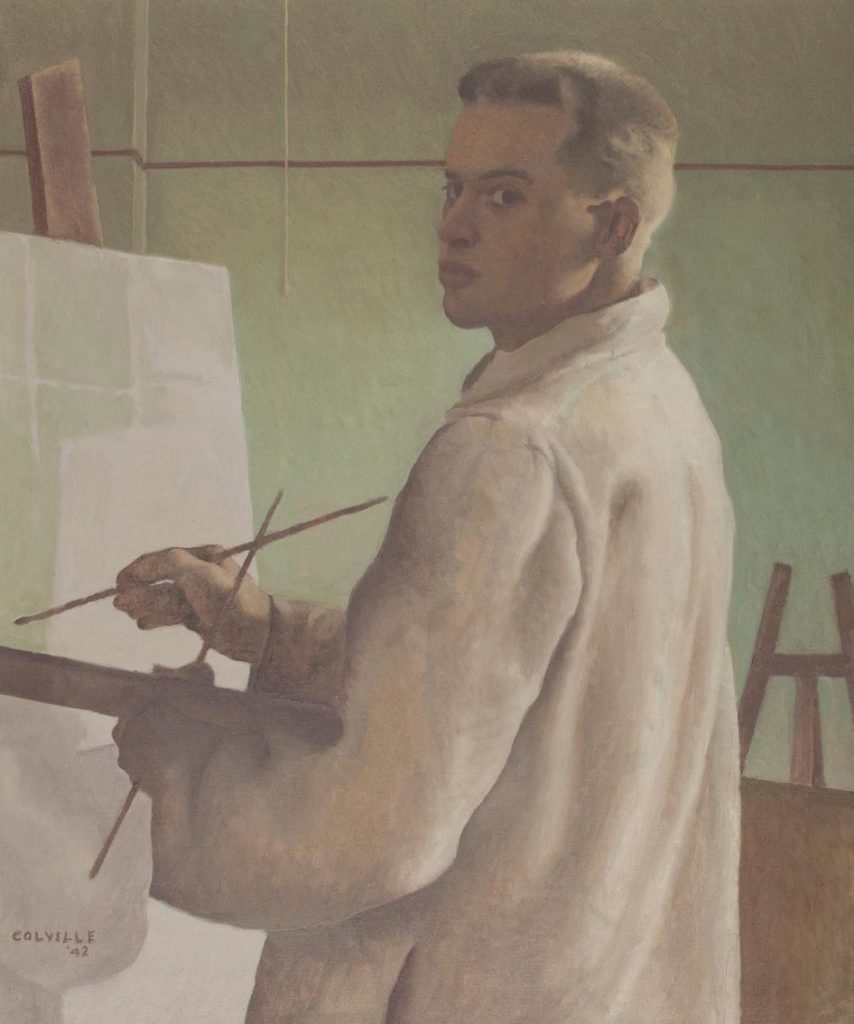

Currently, three of Colville’s works are on view at the Owens, including a student self-portrait that was once thought to have been lost and is not part of his catalogue raisonné.

“He donated [that self-portrait] himself several years ago,” Tisdale says. “As well as the drawings related to his murals… how he put it all together really comes out in those drawings.”

The Owens also operates Colville House, where the artist, his wife Rhoda and their four children lived from 1949 to 1973. It was during these years that the artist produced many of his most important works, including Horse and Train and Nude and Dummy.

“He had quite a bit to do with the renovations of the house,” Tisdale says. “You can imagine: he was so meticulous. He got into the blueprints and made a variety of changes, moving the walls around.”

Atlantic Region Strongly Influenced by Colville

Following his time at Mount Allison, Colville and his family moved to Wolfville, Nova Scotia—his wife’s hometown—where he became a university chancellor from 1981 to 1991 and continued his studio practice.

Acadia University Art Gallery director/curator Laurie Dalton says that the many affectionate anecdotes people have shared about Colville reflect his wide appeal.

“At the opening of our 2009 Colville show, it was amazing to see how much his work affected people of all ages in the community,” Dalton says. “Little kids were coming in with books about him, lining up to get his signature. There were students in high school asking him what tips he had for those who wanted to be an artist. And there were people who had collected his work for 25 years. To me, that shows how his work transcends barriers and speaks to people in multiple different ways.”

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia chief curator Sarah Fillmore says the Atlantic provinces were strongly influenced by his life and work.

“As a sort of mentor and teacher and as an artist who was very present in this region, his loss will be felt. The students that he has had, the kind of visual language that he has helped to create—there’s a strong sense of it.” Fillmore says. “His presence in the community has been very strong, and his role as an educator has been really important. Just about everybody has a story about him and how his work has touched them. It’s pretty extraordinary.”

Paintings Found International Audiences

Gisella Giacalone, director of Mira Godard Gallery, which represented Colville’s work for more than 30 years, says she found it a “pleasure and a privilege” working with Colville.

“I always found him to be a very dignified person with a quiet integrity,” Giacalone says. She says that year in and year out, a new painting would show up from the artist—“that’s the way it worked, nothing to do with age or health. It was always an incredible treat to see the work and show the work and place the work in collections.”

Through his career, Colville’s work wasn’t just placed in regional and national collections, but international ones as well. Exhibitions of his work were held at Marlborough Fine Art in London, the Kunsthalle in Dusseldorf, Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hanover, and Fischer Fine Art in London, among other venues in Hong Kong, Beijing and Tokyo. He also represented Canada at the 1966 Venice Biennale.

Some people, like Owens Art Gallery director/curator Gemey Kelly, hope that in future Colville’s works are exhibited and curated in new ways—and, perhaps, seen with fresh eyes.

“It’s always been a kind of solo-show phenomenon with Alex Colville,” Kelly says. “Even though his work deals with a lot of themes like the body and photography and realism that have been addressed in large group shows, it was never curated into those types of shows. Maybe that will come now.”

Colville’s works are currently on view at the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, the Owens Art Gallery, the Acadia University Art Gallery, and Mira Godard Gallery, among other venues. Colville House is also open to visitors to the end of August.

A self-portrait by Alex Colville, created during his student years at Mount Allison University / image courtesy Owens Art Gallery

A self-portrait by Alex Colville, created during his student years at Mount Allison University / image courtesy Owens Art Gallery