When American-born painter Grafton Tyler Brown opened his exhibition in Victoria in the summer of 1883, the local paper, the Daily British Colonist, recognized the magnitude of the event. “This being the first true art exhibit ever opened here representing the province, the artist should not be allowed to leave disappointed,” declared the publication in early July.

There were 22 landscape paintings on view in the exhibition, held in the Colonist’s new building on Government Street, and most were based on a geological expedition that Brown had taken the year prior that toured the interiors of Southern British Columbia. “Viewed in light of artistic productions they are excellent, but when inspected by those with whom the scenes represented were familiar, their fidelity elicited an extra meed of praise,” wrote a reviewer.

The Colonist allotted Brown the kind of coverage that would turn contemporary publicists green with envy. Nowhere in these inches of publicity, though, does the paper mention Brown’s race.

The omission matters. The artist himself left no personal papers, so an understanding of Brown and his life has been gleaned through elision and second-hand sources. If the Colonist glossed over his race, the publication most likely considered him white. At the time, there was a small but established Black community living in Victoria, but an underlying sense of British (read: white) superiority remained prevalent.

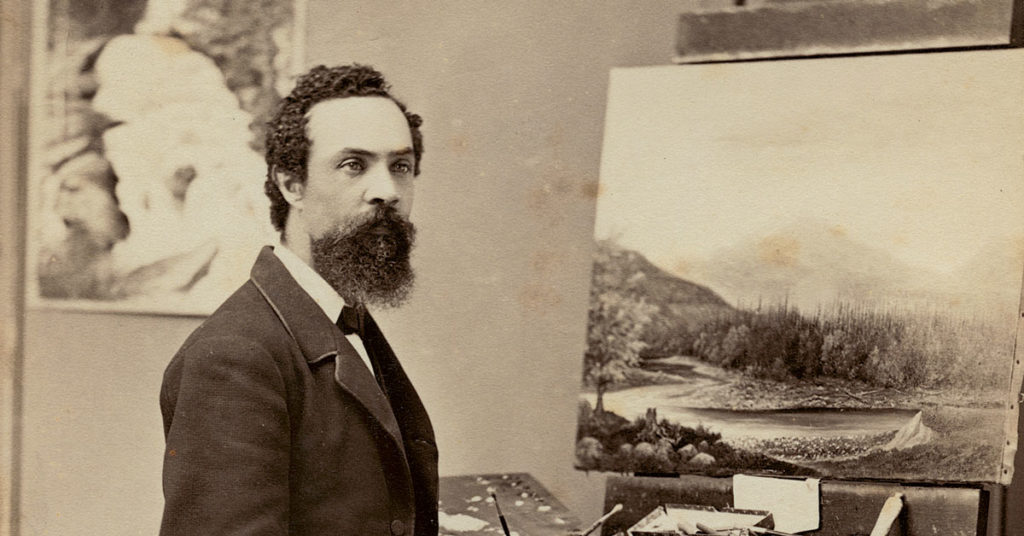

The assumption made about Brown’s whiteness was not exclusive to the paper. Over the course of Brown’s life, his race gradually changed in official documentation. He was listed as Black in early census reports, but on his 1918 death certificate he was identified as white. Brown, the first artist to hold a professional exhibition in British Columbia, was likely only able to do so by passing.

Brown arrived in Victoria in 1882 from San Francisco, where he had gathered uncommon success during the two decades prior, building a reputation for himself as the city’s “coloured printer.” But Brown was always ambitious. Born to free parents in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1841, Brown began his career not as an understudy or an apprentice, but as an employee at the St. George Hotel, in Sacramento, California.

Even before Brown launched a professional art career, he was a successful promoter. “We noticed last evening some very excellent painting done by Grafton T. Brown,” noted the local Sacramento paper in 1859, and the artist was able to parlay this well-received amateur hobby into work as an artist for a printer in San Francisco, eventually working his way up to owning the studio itself.

Grafton Tyler Brown, Giants Castle Mountain, 1883. Oil on canvas, 40.6 x 66 cm. Courtesy Uno Langmann Gallery.

Grafton Tyler Brown, Giants Castle Mountain, 1883. Oil on canvas, 40.6 x 66 cm. Courtesy Uno Langmann Gallery.

While Brown, one of the better-known painters of the American West, accrued impressive press during his lifetime, his two-year sojourn in Canada was virtually unknown until about seven years ago, when John Lutz, a professor at the University of Victoria whose research focuses mostly on First Nations–settler relations and race relations in BC, stumbled across a reproduction of Brown’s sketch of a farm in Saanich, the region where the University of Victoria is now located.

“I was astonished,” Lutz said. “I had no idea there were artists here at that time doing that kind of photorealistic work.” Lutz has since been piecing together details of Brown’s time in the province, tracking down his missing paintings and filling in the biographical blanks.

Perhaps it was the brevity of his stay in Canada that wiped Brown from the historical record. But, with the exception of San Francisco, Brown didn’t stay anywhere for long. Port Townsend, Tacoma, Portland and Helena, where he was joined by Albertine Espey, a white woman originally from France, whom he later married—a union that would be controversial, even dangerous, in many states at the time.

All of Brown’s stops after San Francisco were short until he and Espey reached Saint Paul, Minnesota, and Brown retired from painting. He left no descendants, and took on no apprentices.

But it would be unfair to say that Brown had no influence beyond his own personal success. After all, when Brown was introducing the professional exhibition to Victoria, Emily Carr was 11 years old and living mere minutes away on the same street.

Brown was professionally radical. His paintings of BC, by contrast, are largely conventional. There are landscapes with carefully rendered inlets and bodies of water framed by pine trees, or mountain ranges unfolding across horizons. Brown has created useful historical documentation, but he worked to please a small market, and made commissions for farmers and landowners—his focus during his time in Victoria was to make a living.

Most of the scenes Brown selects are unpopulated, but occasionally, a settlement will appear—given the time in which he worked, these were often the first few buildings in their respective area. In each picturesque work, there is a taste of Manifest Destiny; a sense that the landscapes Brown captures are ripe for settlement and extraction.

When the Colonist refers to him as “the pioneer artist of this intellectual and refined art,” it registers not only in the sense of Brown’s professional accomplishments, but also his sensibility. Brown, who spent his life defying imperial categorization, made a career out of creating imagery that justified a colonial ethos.

The history of passing, like the history of slavery, is often mistakenly considered an exclusively American phenomenon. But any close look at Canada reveals the flaw in this thinking. Brown’s two-year stopover in British Columbia not only provides a vital record of the province during that moment, and of artistic success during that era. It underscores that histories do not stop at borders.

This post is adapted from an article of the same title in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art.

Detail of Grafton Tyler Brown in his Victoria studio, 1883. Image courtesy Royal BC Archives (Image A-08775).

Detail of Grafton Tyler Brown in his Victoria studio, 1883. Image courtesy Royal BC Archives (Image A-08775).