The New York fairs are a focus for many in the art world this week, and the brash, yet formally inventive, GIF artworks of Toronto artist Lorna Mills are gaining steam there and beyond. Today, Mills’s newest GIF artworks debut at Transfer Gallery‘s booth at New York’s Moving Image fair, where they are pegged as a highlight by Rhizome.org program director Zoe Salditch. Here, Mills answers some questions via email about the origins of her practice, her favourite new-media artists and more.

Leah Sandals: How and when did you start making GIFs?

Lorna Mills: Probably around 2005. I had been making digital animations since 1994, but at that time the delivery options were floppy discs and CD-ROMs. The GIF file format didn’t appeal to me until I started looking at Sally McKay‘s GIFs and saw the potential for photo-based GIF work. I was aware of a lot of artists using the file format, but at the time, the emphasis and attention was on graphic tools, and I didn’t really enjoy using them.

LS: Though some of your more recent GIFs tend to abstraction, they often draw upon pop-culture based material that seems to be from YouTube and like sources. How do you find this material, how do you choose and harvest it for use (given that there are so many options available), and how do you go about developing ideas or compositions?

LM: I spend at least an hour a day looking at GIFs through Reddit, Google+, Porn Fail and a bunch of Russian sites. I am drawn to gratuitous Internet filth, interspecies romance, masturbating penguins and people wanking with plastic dolphins. I’m more interested in subcultures than I am in pop culture. Pop culture references are almost always about success (that’s why they’re popular). I’m more interested in marginalized peculiarity. And really, there’s a good reason why some activities are marginalized but I can’t help my feelings of affection for those willing to perform inane activities in front of a video camera.

LS: Some of your work also has an absurd or in-your-face quality. Do you think other contemporary artists often play it too safe? Why or why not?

LM: That absurd quality is one of the conditions of my Internet, basically because I spend so much time looking at GIFs created by people who don’t position themselves as artists but still revel in the recorded muck of not-so-popular culture. Most of my contemporaries making art that’s distributed online are not playing it safe, and that is generally not a criticism I’d make towards artists working in other mediums. The safe-playing generally happens at a different level of the art industry. But in all fairness, the art-world machine still supports my visual excesses far more than corporate social media does. Google+ and Facebook have removed various art pieces over the years, and I have had work banned on Live Leak as well. (“Permanent Ban on Live Leak” will go on my gravestone.)

LS: Some of your press material has mentioned that your work comes out of a tradition of “obsessive” making in analog mediums such as Ilfochrome, painting and Super 8 film. This prompted me to wonder whether Internet-based art (or Internet-based making in general) is particularly suited to obsessive tendencies. Certainly things like Google Alerts, push notifications and social-media software encourage (and often immediately reward) a kind of obsessive checking. Am I out on a limb here, or is the Internet uniquely suited to serve artists who tend to an obsessive practice or tendency?

LM: Absolutely! Though paradoxically, almost every net artist I know has the attention span of a flea when we are away from the keyboard, actually talking to each other.

LS: This week, your work is at Transfer Gallery‘s booth at the Moving Image fair in New York and in January, you showed your work at Unpainted, a new new-media art fair in Munich. Some think that it is difficult to format GIF art for sale. What are your views on this situation? What ways have you or your dealers tried to format GIF art for the marketplace?

LM: New media collectors don’t have a problem purchasing a GIF delivered on a USB drive. However, many other collectors would be mystified by this. For art fairs, like Unpainted in Munich and the Moving Image fair in New York, Transfer is selling them playing on dedicated tablets. (One GIF per tablet.)

LS: You recently showed a lenticular print based on a GIF as part of the Art F City Roast at Postmasters Gallery in New York. It only very recently occurred to me that lenticular prints are analog GIFs. (I’m slow that way.) Do you want to do more lenticular prints of your GIFs? Why or why not?

LM: I’m madly in love with lenticulars, I’ve been collecting them for years. Most lenticulars that you see are made up of 2 or 3 images at the most. The artist Anthony Antonellis exhibited a gorgeous series of lenticular prints several years ago, and more recently, Rafaël Rozendaal has been mining that territory as well. I didn’t see it working for me until a company called GifPop opened in Brooklyn with the technology to print 10-frame lenticulars, allowing me to confidently bring my very specific lack of taste and appalling aesthetic judgment to the fine-art table.

LS: What three GIF artists or artworks do you really enjoy right now and why?

LM: I could name more than three, but number one pick would be Francoise Gamma, a very enigmatic Spanish artist, who’s figurative GIF work is tortured, frenzied, sexy and ultimately so very graceful. Number two is Hyo Myoung Kim from the UK, who is constantly surprising with new forms of digitally induced movement. Last but not least is Rollin Leonard, who I have collaborated with in the past and will again in the future. We share an interest in photo-based animations that most civilized people would find rather lamentable.

LS: In your non-art life (if such a thing exists!) you work as a game programmer and Internet video producer. Do you ever get sick of working digitally? If so, what do you to art-wise or otherwise when that happens?

LM: No, I haven’t got sick of working digitally, but I do get sick from sitting in front of my computer for 14 hours a day when I have a lot of art and non-art deadlines. I’ve always thought about technology, and complex or simple tools, no matter what medium I’ve worked in, so I can’t imagine anything else. I am a total failure as a human on the rare occasions when the power goes out. To paraphrase the artist Andrew Harwood, I am one blown fuse away from irrelevance.

LS: What is your hope for the coming year in terms of your art practice, GIF or non-GIF?

LM: No power outages this summer. I’m curating a large, collaborative, four-episode video project that involves art about art about television about the Internet. It will ultimately include about 120 digital artists, both Canadian and international, by the time I’m finished. The first episode, involving 30 artists, is currently being produced at the invitation of the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. My big hope is to get the other three episodes done by the end of this year.

LS: Is there anything else you wish people would consider when looking at your art in particular, or GIF art in general?

LM: Probably that I’m much more ravingly formal and precise than one would expect considering the source animations that I use.

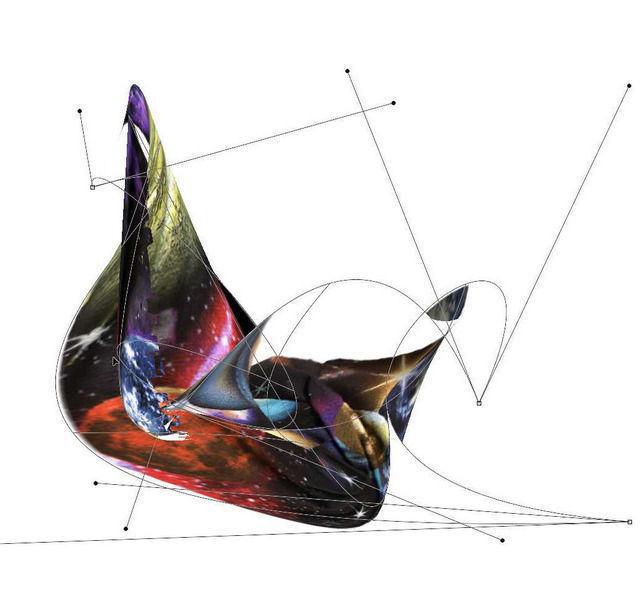

Lorna Mills, Scrap: Rayon, 2014. Animated GIF. Courtesy the artist and Transfer Gallery.

Lorna Mills, Scrap: Rayon, 2014. Animated GIF. Courtesy the artist and Transfer Gallery.