Meghan Price

Geological time weaves through, moulds into and engulfs human timescales. Rather than the prevailing association of stone with solidity and stasis, Toronto artist Meghan Price emphasizes this “liveliness and fluidity of the geologic” through intricate textile works, drawings, prints and videos. Geological formations are infinitely in flux and hold knowledge of how the earth changes over time. In Hutton’s Unconformity (2018), Price embeds and translates macroscopic processes of deep time into fine strata of handwoven cotton, wool and plastic yarns made from waste. Colourful dots and streams of red, blue and yellow enmesh with the softened stoicism of handmade black-and-white layers of earth. This translation is defined by structure and the weaver’s time; as the weaver inserts lines of thread horizontally, layers accrue vertically, thus also “recording the time of the body.” Price explains that she often employs handwork to “physically and intellectually process earth’s timescale through acts of making, or otherwise act as mediator/calibrator.” Hutton’s Unconformity references an illustration from 18th-century geologist James Hutton that shows an “unconformity,” in which two rock formations created in different historical periods become adjoined. Price’s “unconformity” of plastic marks the environmental consequences of our current time. She champions the unknowable as a way to afford agency to the natural world.

Anna Binta Diallo, Wanderings, 2019. Collages printed on Photo-Tex removable adhesive fabric and mount ed on walls, aluminum composite and PVC board, dimensions variable.

Anna Binta Diallo, Wanderings, 2019. Collages printed on Photo-Tex removable adhesive fabric and mount ed on walls, aluminum composite and PVC board, dimensions variable.

Anna Binta Diallo

Images make and spread the worldviews and cultural myths that often become reality. By remixing material from the visual culture of magazines, archives, science, literature and autobiographical sources, Anna Binta Diallo’s collages display the adaptability of images and refuse fixed ideas of collective and self-identity. “Erasing, rewriting and recreating are always in my head and drive my practice,” says the Montreal artist. The figures in her wall-sized collages appear like global and galactic travellers built from the textures, debris and remnants of various cultural inheritances. In Wanderings (2019), composite figures and animals scatter across the spaces they inhabit; they appear floating without horizon lines, in their own private stories, yet interacting with each other across opened space and time. For these narrative pockets, Diallo collects materials and stories, including folktales from around the world and her own Senegalese, French Canadian and Métis heritage. She finds common elements between stories, some passed entirely through memory, to explore the transcultural aesthetics of fragmented identities. Even images with heavy histories are relieved from their original contexts, literally cut apart to create new origins and purposes for their existence. The faces of Diallo’s figures are gently shaped pieces of star systems, skies or close views of landforms. They wear the rich patterns of forests, black-and-white ethnographic drawings and vibrant purple fabric—infinitely alterable assemblages of what was and what is to come.

Catherine Telford Keogh, X Supplement Aggregate Simulator X (Agatha knew that she was the kind of being that could survive at the bottom of the ocean in below zero temperatures for months or on a deserted planet in space. She had that kind of unbroken restraint and will.), 2019. Glass, Plexiglas®, Brite White Matte Formica®, Pigmented FlexFoam-iT! ® III, Dial® Omega Moisture Glycerin Soap with Sea Berries, Lasercut Deconstructed Plexiglas® Logos, Nature’s Path® Qi’a® Superfood Apple Cinnamon Chia Buckwheat and Hemp Cereal, Extra® Sugar Free Gum, etc., 35.5 cm x 1.1 6 m x 1.16 m. Photo: Laura Findlay.

Catherine Telford Keogh, X Supplement Aggregate Simulator X (Agatha knew that she was the kind of being that could survive at the bottom of the ocean in below zero temperatures for months or on a deserted planet in space. She had that kind of unbroken restraint and will.), 2019. Glass, Plexiglas®, Brite White Matte Formica®, Pigmented FlexFoam-iT! ® III, Dial® Omega Moisture Glycerin Soap with Sea Berries, Lasercut Deconstructed Plexiglas® Logos, Nature’s Path® Qi’a® Superfood Apple Cinnamon Chia Buckwheat and Hemp Cereal, Extra® Sugar Free Gum, etc., 35.5 cm x 1.1 6 m x 1.16 m. Photo: Laura Findlay.

Catherine Telford Keogh

Based on the properties of decaying food, consumer objects, cellular matter, colours, smells and sculptural forms, Toronto artist Catherine Telford Keogh’s practice is at once attuned to the specifics of matter and the instability of material as it transforms or disappears. “I’m really interested in assemblage, and the way in which the body is an assemblage of a multitude of materials that are both organic and inorganic,” Telford Keogh explains. As she thinks about how certain objects operate in the world—it could be the particular scent of branded dish soap, dog food, petroleum or pepperoni sticks—she complicates their typical contexts beyond easy distinction and recognition, often with class, capital and ecological dimensions. Inside her circular floor sculptures that resemble petri dishes or ashtrays, detritus and food are submerged in resin and pinned under glass to create a kind of petrified form—a compressed visual shorthand for complex narratives of life and consumption. Her recent work X LOWLIFE X (flows of power. greasy wide beak merganser duck. petroleum) (2019), for example, recalls a dish of crude oil, a black hole, in which fossilization is misleading: the Bick’s dill pickles, maraschino cherries, Oreo cookies, cereal and other foods encased inside continuously break down. Telford Keogh has a way of adjusting to scale that connects the molecular to the everyday, defining matter’s innate porousness. In a current collaboration with scientist Andrew Pelling, she is growing a cancerous cell line with jellyfish protein on sculptural scaffolds, navigating the social meanings of material permutation.

Eve Tagny, We weight on the land - Legacy, 2019. Alocasia, concrete block, flowers, soil, stones, gold leaf, polytarp, unfired clay pot and video projection, dimensions variable. Courtesy Cooper Cole.

Eve Tagny, We weight on the land - Legacy, 2019. Alocasia, concrete block, flowers, soil, stones, gold leaf, polytarp, unfired clay pot and video projection, dimensions variable. Courtesy Cooper Cole.

Eve Tagny

If grief and loss are ruptures in time, Eve Tagny believes in restoring them into the natural cycles that are a part of renewal processes. The Montreal artist embeds still and moving images into organic materials, which continue to change form over the course of an exhibition. Soil, clay, rocks, leaves and wildflowers are rendered as witnesses, healing elements and containers for memory that become inseparable from the images they envelop. Tagny cultivates the gallery site as a garden, influenced by her hand but recognizing the life cycles outside its white walls. Her string of solo and group exhibitions over the past year traces a narrative continuum that feels out the material embodiment of love and bereavement. In “Lost Love – Saisons futures” this past fall at Gallery 44, the intensity of love began in summertime in South Africa, unravelled with a sudden death in autumn and was followed by the grieving period of winter and a new landscape in spring. On a mound of concrete rubble, a small projected video of two lovers’ interwoven hands became the physical shape of ruin. For Tagny, the material of translucent plastic is also potent as an artificial barrier between life and death in forensics and as a protective cloak over trees and soil mounds. In “Lost Love,” a hanging plastic partition, through which light and shapes blur, marked a passage into autumn, and eventually renewal. Tagny affirms the tension between the preservation of memory and natural forces that are always “finding space for life.”

Xuan Ye, ERROAR!#4 The Oral Logic I (detail), 2019 Single-channel HD video, interactive software, laser-engraved mirror, 3D prints and generative poetry on paper scroll, dimensions variable. Courtesy Pari Nadimi.

Xuan Ye, ERROAR!#4 The Oral Logic I (detail), 2019 Single-channel HD video, interactive software, laser-engraved mirror, 3D prints and generative poetry on paper scroll, dimensions variable. Courtesy Pari Nadimi.

Xuan Ye

Toronto artist Xuan Ye creates multifarious installations and interactive digital works that treat language as code as speech—interdependent systems that construct human subjectivity through the ever-muddled boundaries between them. Ye says while “language is not pure sign,” it nonetheless forms the material world. Language gathers a separate body, too, in the physical coding behind the applications so many of us interface with. Through written algorithms, sound, image and text, Ye probes our symbiotic relationship to technology, stripped apart to reveal and destruct the most energy-sucking parts of this relation (such as intimacy with capital). In ERROAR!#4 The Oral Logic I (2019), a tablet screen recounts the true story of an early 2000s computer simulation in which two AI agents (Adam and Eve) ate a third AI agent because they mistook him for food. This uncanny case of virtual cannibalism becomes a metaphor for how screens and code reconfigure (or eat) us as we interact with them, and vice versa. Here, a dissonant sound piece plays over a seemingly endless scroll of generative and non-aestheticized poetry, coded by the artist. For Ye, who is informed by media theory as well as a rich personal history—being a musician, performer and learning to code for a livelihood—interfacing with code is strongly tied to material survival, although it can also alienate one from their body. Following EveryLetterCyborg V1.2 (2017–18), a bot programmed to tweet restructured passages from Donna Haraway’s 1985 “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Ye is working on a chatbot that communicates through sound.

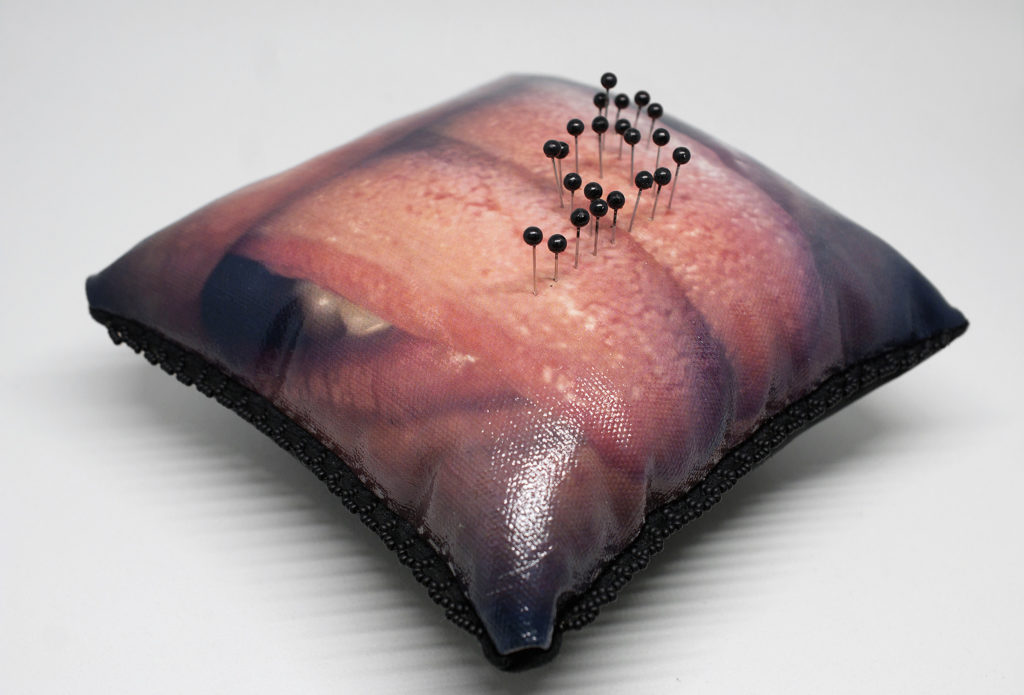

Catherine Blackburn, ee leh, 2017. Seed beads, pins, velvet and gel photo transfer on cotton, 15.2 x 15.2 x 10.1 cm.

Catherine Blackburn, ee leh, 2017. Seed beads, pins, velvet and gel photo transfer on cotton, 15.2 x 15.2 x 10.1 cm.

Catherine Blackburn

Survivance, deep resistance and kinship love abound in multidisciplinary artist and jeweller Catherine Blackburn’s gestures of marking and making. For the artist, the way her hands bear knowledge carries ancestral connections and suggests how Indigenous bodies hold power and resurgence. Blackburn, a member of English River Dene First Nation and currently based in Leask, Saskatchewan, explores these threads through beadwork, “a living resistance” that allows her to connect to personal history as well as challenge how contemporary Indigenous existence is understood. Our Mother(s) Tongue (2017) displays a drive for reclamation that’s born from the immense loss caused by Canada’s residential school system. Blackburn renders a series of pincushions viscerally violent by printing close-up photos of her family members’ tongues on the fabric and then piercing the images with pins. Where pins were used to punish Indigenous children for speaking their languages (their tongues were pierced with them), Blackburn’s pins form Dene syllabics, to memorialize language that endures beyond. In an accompanying set of five framed images, the artist beaded Dene language and floral motifs onto photos of the tongues, facilitated by a healing exchange with her mother who helped translate Dene words into phonetics. Lost language is physically reinscribed: “Through redirecting notions of grief I can reclaim, Indigenize and reinforce Indigenous strength,” says Blackburn. Her recent garment series, New Age Warriors (2018–19), embodies just this vision with beaded and structural armour protecting those who will fight colonialism—champions of an imagined future (and present reality).

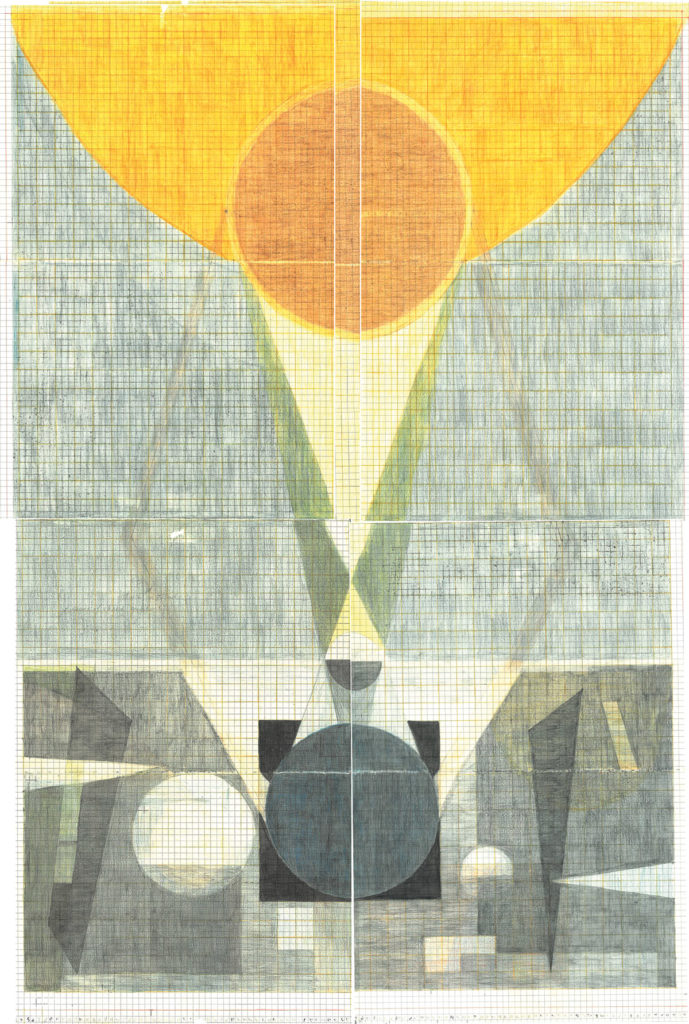

Mehrnaz Rohbakhsh, May 1919 Study for an Eclipse (Syzygy: An Absurdist Opera), 2017. Coloured pencil on paper, 1.52 m x 55.9 cm.

Mehrnaz Rohbakhsh, May 1919 Study for an Eclipse (Syzygy: An Absurdist Opera), 2017. Coloured pencil on paper, 1.52 m x 55.9 cm.

Mehrnaz Rohbakhsh

Driven by an intense curiosity of myriad reference points, Toronto artist Mehrnaz Rohbakhsh feels out knowledge and realistic rebellions through drawing, cosmological sound, light, dance and offerings. She has thrown opera into the streets in free, BYOB style to unbind it from hierarchy in Syzygy: An Absurdist Opera (2016) and organized an audio-kinetic performance in front of David Dunlap Observatory in An Expanded Universe (Homage to Page) (2018), with both works drawing from theories of relativity. It would be easy to listen for ages to Rohbakhsh make connections, from Vera Rubin, a pioneering astronomer on the evidence for dark matter, to Michio Kaku, who connects string theory and music, to Iannis Xenakis, a composer who created intricate aural graphs. “Both music and astronomy are directed by time,” she notes, which makes translation simpler than you might think but still incredibly subjective. Rohbakhsh explains that on a physics graph where the x axis is time and y is space, music swaps the y axis for pitch. Her Mapping Time: Harmonic Studies for Vera Rubin (2017) begins at and expands from Rubin’s studies of dark matter. Through large renditions of Rubin’s diagrams, sensitively drawn with pencil on plots of graph paper, their notations transposed into accompanying audio works, Rohbakhsh finds the poetry in a “dissertation on nothing, on the void…pages graphing out emptiness.”

Andrea Roberts, CRISIS CANON, 2019. Sandblasted text on concrete, sound score, performance, 2.9 x 3.1 x 6 m. Photo: Robert Szkolnicki.

Andrea Roberts, CRISIS CANON, 2019. Sandblasted text on concrete, sound score, performance, 2.9 x 3.1 x 6 m. Photo: Robert Szkolnicki.

Andrea Roberts

For the 2019 STAGES biennial, Winnipeg artist Andrea Roberts created CRISIS CANON on the site of a never-built British-American cement plant in Rosser, Manitoba. Drawing from sound, technology and performance, Roberts’s installations emphasize critical connections between material, history and labour. CRISIS CANON is the largest and most permanent work to date for the artist, who has also performed in DIY punk and noise bands and is wary of what it means to “leave a legacy” in the long arc of history. To them, the failed development in Rosser represents an assumption of inevitable industrialization and expansion. “What drew me to the site is that it’s an unbuilt ruin,” they explain, “a speculative insertion of these things into the land…weird portals into imagining another history.” Circular groupings of concrete pillars—the evidence of preliminary cement strength tests—eerily convey forgotten intentions, which Roberts multiplied with other lost contexts: On an existing massive cement block, they sandblasted a mistranslation of Cicero’s “lorem ipsum” text, often used as a placeholder in graphic design. Vocalists and noise musicians performed a five-piece score composed by Roberts, partly including arrangements of the labour anthem The Internationale and a song from a Coca-Cola commercial. Both anthems claim different ways of uniting the world, a striking contrast of the desires and failures of leftist and capitalist ideologies. As Roberts says, “I’m under no illusion…I feel invested in creating alternative networks of distribution, exhibition and conversations, but I don’t feel like I can exist apart from anything.”

Julia Dahee Hong, Serving Suggestions, 2019. PVC vinyl and unique S-hooks, dimensions variable. Photo: Felix Rapp.

Julia Dahee Hong, Serving Suggestions, 2019. PVC vinyl and unique S-hooks, dimensions variable. Photo: Felix Rapp.

Julia Dahee Hong

“I had this strong urge to materialize,” Julia Dahee Hong says of her initial writing and photography practice. Expanding into installation, sculpture and performance, Hong plays with visual cues from advertising and commercial aesthetics to estrange them from their usual ideologies. For two years, the Vancouver-born artist lived and worked in Antwerp, where she recently finished her MFA, and is now based in Brussels. For her 2018 exhibition in Copenhagen, titled “Sky’s The Limit,” she presented photos of white people with glowing skin and muscled physiques, gulping down colourful sports drinks with chins tilted toward a bright blue sky. In these absurd images of willpower and fitness, as elsewhere in her practice, Hong is fascinated with “what you have to believe for it to work, or not work.” The “it” is often middle-class aspirations under capitalism, as well as broader ideas of service, ability and consumption. Her installations Something You Cannot See, Smell, Touch or Taste and Serving Suggestions (both 2019) alter familiar templates from service industries to look at intangible belief systems that have material consequence. Silver platters are etched with service industry slogans, catering tables become sombre sculptures, Spam scanned through a sandwich bag provokes fleshy feelings. Hong introduces a kind of placebo effect behind what some of us value or uphold, a reminder that even alienating systems need you to buy into them.

Liam Johnstone, A long day’s journey caught by night, 2019. Teardrop tea, ink-jet print, dried yew leaves and neon, 30.5 x 61 x 76.2 cm.

Liam Johnstone, A long day’s journey caught by night, 2019. Teardrop tea, ink-jet print, dried yew leaves and neon, 30.5 x 61 x 76.2 cm.

Liam Johnstone

How do ideas of value vary according to different worldviews, idiosyncratic and shared? In an experimental exchange, Liam Johnstone’s performative installation Back-Alley Bargains & Dancing Waters (2019) left the determination of value up to visitors. Held in a shop set up in his former Vancouver studio as part of the artist-run gallery Duplex, Johnstone asked the public to bring something to exchange for a jar of homemade “fire cider,” a super-elixir of apple cider vinegar fermented with flowers and an assortment of herbs and vegetables. Many brought specific objects they had made, and some offerings stood out: two half-remembered songs sung by a friend, one handmade ceramic unicorn (an edition of 1,000) given by a stranger—and someone even brought nothing. During these “shop” exchanges, a sound piece played that was modelled after sonic healing frequencies (contributing to the elixir’s “dancing waters”). Johnstone wished for visitors to imbue their jar of elixir with their own intentions, whether they saw it as food, art or otherwise. To him, the exchange goes beyond the pure material swap and reflects his alchemical idea of communication being a driving force of the universe: “Everything has the potential to be a form of communication” and to transform. Previously working in sculpture, sound and light, Johnstone has recently begun to plan more performance-based projects around the concepts of shop and shopkeeper, possibly mounting guerrilla installations in the future.

Meghan Price, Hutton’s Unconformity (detail), 2018. Handwoven cotton, wool and plastic waste, 123 x 51 in.

Meghan Price, Hutton’s Unconformity (detail), 2018. Handwoven cotton, wool and plastic waste, 123 x 51 in.