Camille Turner, Lisa Myers, Carmen Papalia, Jaime Koebel and Pamila Matharu—these artists, who we focused on last month in an article called “Step by Step,” are leading the way in creating innovative, powerful and politically resistant walking-based art.

But what structures and scaffolds actually exist to highlight or support the work of walking-based artists, or walking-based art?

Given that walking is a highly mobile activity, pinning it down in traditional exhibitions, or collecting it into standard museums, can prove a challenge.

There have been successful efforts on this front, like the exhibition “Artists’ Walks,” organized by Toronto-based curator Earl Miller for Dorsky Gallery in New York in fall 2013 and for the Art Gallery of Peterborough in winter 2014.

But it is also worth considering some more recent attempts (in Canada and elsewhere) to create scaffolds and structures for investigating walking-related art and artists. Here are four worth contemplating.

The Museum of Walking helps program walks of various kinds, as well as exhibitions, talks and an archive. Photo: Facebook.

The Museum of Walking helps program walks of various kinds, as well as exhibitions, talks and an archive. Photo: Facebook.

The Museum of Walking

On a hot, sunny Saturday morning in March of this year, some 500 people met up at Rio Salado—an old landfill turned nature preserve in industrial South Phoenix, Arizona. As hummingbirds sucked nectar from orange-coloured blossoms, groups of 10 to 20 people set off on a long walk in timed “waves.”

All of the assembled were all there to participate in a “large-scale contemplative walk” organized by the Museum of Walking, a multifaceted project co-founded by Phoenix artists Angela Ellsworth and Steven J. Yazzie.

The Museum of Walking exists in part as “a small-but-mighty archive and library” on art and walking housed in Ellsworth’s office at Arizona State University. (“We made an agreement that whatever we collected [for the archive] we have to be able to carry on our person for at least five blocks,” Ellsworth says. “So that it’s easily movable.”) The office has a glass door, so that any related installations or book stacks can be viewed anytime. Small exhibitions of artists doing walking-related art are also part of the roster, and talks, too.

The museum also exists within semi-regular programs of group walks. In May 2016 was “Walk the Indian School” with Patty Talahongva—an alumnus’ tour of one of the now-defunct but longest-running “Indian Schools” in the USA, which Talahongva hopes can be turned into an Indigenous cultural centre. In November 2015, “Desire Lines: Women Walking as Making” journeyed to and around Jody Pinto’s 1992 land-art piece Papago Park City Boundary Project while offering an in-motion time and space to discuss other women artists who have used walking in their work, such as Mona Hatoum, Eve Mosher and Janine Antoni. And in October 2015, a walk was organized along the route of Postcommodity’s two-mile-long land-art piece Repellent Eye, which stretched across the US-Mexico border in Southern Arizona (the full course of this planned walk was obstructed by the US-Mexico border fence).

These varied programs add up to an approach that pursues both the political and the poetic—and the intersecting paths between.

“There is this long lineage of white men walking on land [in art and in North America],” says Ellsworth, who also acknowledges the colonial dimensions of her Mormon settler ancestry and its relations to narratives of journeying and walking. “So I think that the Museum of Walking is to consider always the first people of the land.”

Contemplation—in the form of no-cellphone-use policies on many walks—is one mode that Ellsworth tries to encourage.

“Saying no cellphones was kind of a huge risk,” Ellsworth says. “But I was just like, let it go. In this day and age, that is tough to ask of people. And it also tough for people to not be talking, to just listen. It’s not about taking voice away—it’s about listening, and listening in a deeper, wider sense.”

Certainly, the silence, and the lack of electronic distractions, amplified many walkers’ experience of the local soundscapes during that massive March walk in Rio Salado—from the engines roaring over a busy overpass to a gentle breeze lifting white poplar seeds off a river-side tree. Ellsworth and the March walk team also accentuated listening opportunities by incorporating intimate performances by various musicians along the walk route.

Ellsworth finds that, especially in recent months, she’s seen a greater community need for these types of contemplative walk experiences.

“The biggest walk we ever did [before March] was a full-moon silent walk in the desert, right after the last US election,” Ellsworth says. Typically, before that, 25 to 30 people would RSVP for a walk. But on that second weekend of November 2016, the reservations were double that—60 to 75 people, with more who just showed up on site.

“Because the moon was so bright, no one was using flashlights,” Ellsworth said. “There was just this group of 75-plus people moving up the mountain.”

On April 1 near Hamilton, Walking Lab held an event called Stone Walk on the Bruce Trail: Queering the Trail, which troubled colonial experiences of walking with presentations by a geologist, various artists and Indigenous scholars. Artist Mary Tremonte made these pennants for the walkers to hold. Photo: Twitter.

On April 1 near Hamilton, Walking Lab held an event called Stone Walk on the Bruce Trail: Queering the Trail, which troubled colonial experiences of walking with presentations by a geologist, various artists and Indigenous scholars. Artist Mary Tremonte made these pennants for the walkers to hold. Photo: Twitter.

Walking Lab

In the morning I walk an improvised route through the city,

in the afternoon I walk exactly the same route again.

This proposition, titled An Improvised Route 1&2, by Dutch artist Frans Van Lent, is one of 20 suggestions in The Propositional Walking Project, an online and offline framework organized by Walking Lab—itself an active laboratory for research and development on walking methodologies based in Toronto.

On its website, the Walking Lab offers documentation and links to dozens of projects, residencies and events it has programmed in its several years of existence: from a walking pinhole camera project (to slow the tendency for walkers and others in motion to speed up journeys with a GoPro camera) to an upcoming research-creation project in Iceland’s northern fjords looking at “rocks as queer archives.”

Stephanie Springgay, principal investigator in the Walking Lab project, and also an associate professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, seeks to look at walking as research-creation, and also through a critical lens.

For example, Walking Lab’s recent Stone Walk on the Bruce Trail: Queering the Trail event, which took place in April in Hamilton, Ontario, “sought to disrupt the heteronormative, settler colonial ways in which walking is conventionally understood through three heteronormative tropes—the flâneur, the dérive and the romantic colonial long walk,” Springgay says.

To enable this disruption of norms in Queering the Trail, Springgay and other Walking Lab members organized presentations by geologist Katherine Wallace along the route—emphasizing a millions-of-years slowness that counteracts the speedy use of landscape by cyclists and runners along the trail. The team also brought in presentations by Algonquin/Mohawk social work professor Bonnie Freedman, whose research has focused on Haudenosaunee youth-led journeys traveling on foot through ancestral lands.

“A critique of the concept of place in walking is that we tend to walk on a lot of land, but we rarely take into consideration what that means in terms of colonization,” Springgay explains. “Predominantly, walking studies and mobility studies have come out of a European discourse.”

This summer, Public Studio will be walking all 900 kilometres of the Bruce Trail as part of its ongoing project The New Field, and Walking Lab will be joining them for a section of that hike with a related event titled “Cripping the Trail.”

The initial impetus for Walking Lab, Springgay says, “was less about increasing visibility” of walking and more about bringing together work that was already happening “inside and outside of the arts” in North America, the UK, Australia and beyond—as well as asking questions about that work, and its predominant emphasis on the cult of the individual.

“Walking Lab often uses the term ‘walking with,’” says Springgay. “Even if you do a walk with one other person, what does that mean? How do we put habits and thoughts and bodies in this frictional tension with each other? How do we tend to these different concepts up against or through walking?”

Halifax’s Narratives in Space and Time Society invited community members to “Downhill from Here,” a program of movement and actions on the slopes of Citadel Hill, in September 2016. The event was commissioned by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia with help from Future Roots. Photo: James Maclean via Facebook.

Halifax’s Narratives in Space and Time Society invited community members to “Downhill from Here,” a program of movement and actions on the slopes of Citadel Hill, in September 2016. The event was commissioned by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia with help from Future Roots. Photo: James Maclean via Facebook.

Narratives in Space and Time

Halifax artist Barbara Lounder started as a sculptor. But of late she has found that walking is one of the main practices she is engaged in creatively—both for herself, and for her community.

“I think it [my interest in art and walking] developed pretty naturally out of an interest in spatial practices,” Lounder says. “My expanded field [of sculpture] moved completely outside of the domains of sculpture and installation and the gallery and the studio as well—it came as a natural development of that trajectory in my work.”

Besides doing her own individual projects—creating and using walking sticks that have mark-making devices on the bottom—Lounder has co-created a scaffold for a wider walking practice in the form of Narratives in Space and Time, “an interdisciplinary creative research group working on projects involving mobile media and walking.”

Among Narratives in Space and Time’s projects is Downhill from Here, a series of group movements actions and performances on slopes of Citadel Hill in September 2016.

But the group’s primary focus right now is Walking the Debris Field, a multi-year project that is “using walking as a means of exploring the areas affected by the Halifax Explosion, but also engaging a very diverse public in these creative investigations,” says Lounder.

As an example of one activity in Walking the Debris Field, Mi’kmaq filmmaker Catherine Martin described to a public walking group the manner in which the Halifax Explosion obliterated the Mi’kmaq village of Turtle Grove—a tale which is often overshadowed in the predominant Halifax Explosion narrative of a British colonial city lost.

“As our existence becomes more critical in the world, everything from politics to the environment and engagement with everyday life is more necessary for a lot of artists,” Lounder says. “There is this desire to have a more meaningful relationship with audiences, but also with experiences and environments outside of the art world…and I think of walking as a pretty basic kind of practice that is almost sort of like the baseline for that kind of thinking.”

There is timeliness to the current Narratives in Space and Time project. This year, 2017, is the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion, which was the largest man-made explosion in history prior to the development of nuclear weapons, and which destroyed much of Halifax in addition to killing some 2,000 residents.

“It’s work that brings research and creation together in a together in a very new way for me,” says Lounder. “It is mostly a form of working that is taking place in neighbourhoods, and with groups of people that can range from a handful to up to 100 people. For me, it has been a very exciting way to experience the space of the city differently and also to connect with people who would never find themselves in a gallery, or even a museum, but who are very committed to ideas about space and community and creativity.”

Collaborators for Narratives in Space and Time are various, from storytellers, choir members and arborists to teenagers from a local housing project who work as safety marshals at all the walking events. And their work will be featured an exhibition this fall at the Dalhousie Art Gallery, which presents other issues about resolving mobile work with a static space.

Questions of how to remember a historical event one never experienced directly are also very present in the Walking the Debris Field project. As part of each of their community walks for this project, Narratives in Space and Time commissions an architectural model of a building that was destroyed in the Halifax explosion. They then burn each of these models at some point during a given walk.

“There is always a thoughtful reflection that happens at that time,” says Lounder—a reflection that will be revived when her collective mounts an exhibition at the Nova Scotia Archives in December, the same month the Halifax Explosion happened. At the archives, they will have both photographs of the models, aflame, and reconstructions of each model.

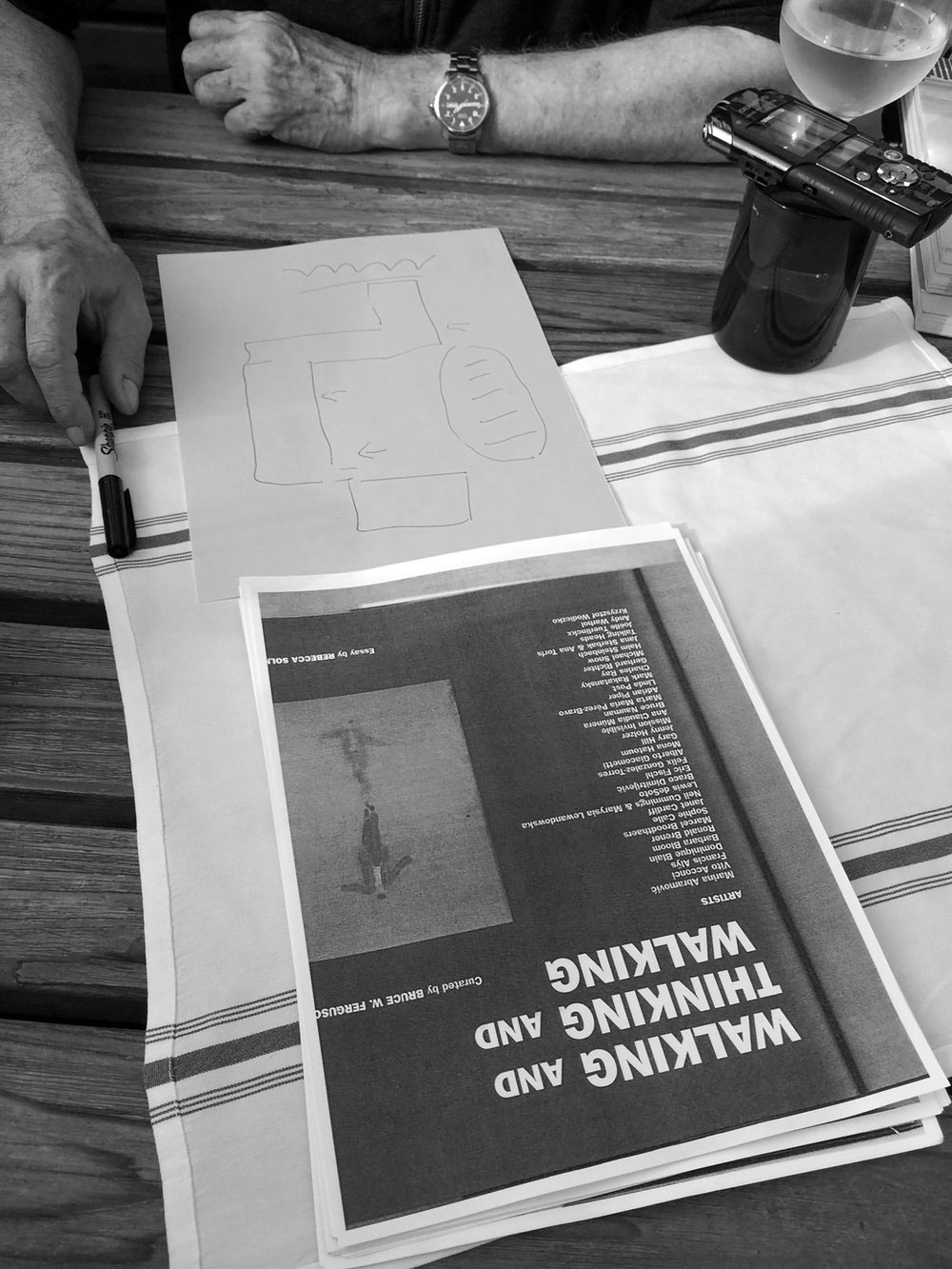

Bruce Ferguson revisits his landmark 1996 exhibition catalogue for “Walking and Thinking and Walking” in mimeographed form for a re-examination of that project that took place in 2017.

Bruce Ferguson revisits his landmark 1996 exhibition catalogue for “Walking and Thinking and Walking” in mimeographed form for a re-examination of that project that took place in 2017.

“Walking and Thinking and Walking” Revisited

Well before he became a world-renowned curator and art-school leader, Bruce Ferguson was a boy walking through dry-grassed Southern Alberta coulees, following curving earthen surfaces carved by Pleistocene glaciers and prairie rivers.

“I remember that landscape so well—walking in the prairies, walking in the mountains, walking in rivers, the works,” Ferguson says over the phone from Los Angeles, where he is now president of the Otis College of Art and Design.

In 1996, far from that Alberta landscape where he wandered as a youth, Ferguson curated one of the breakthrough survey exhibitions to link art and walking: “Walking and Thinking and Walking” at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark.

Not only did “Walking and Thinking and Walking” put walking clearly on the art-world map as a form of practice—it also helped launch what would become some renowned practices this realm, like Janet Cardiff’s audio walks (the first one she ever did was commissioned especially for “Walking and Thinking and Walking”) and Rebecca Solnit’s writings on art and walking collected in the now-classic 2000 tome Wanderlust (Solnit wrote an essay for the “Walking and Thinking and Walking” catalogue, and also installed quotations about walking on the windows of the museum during the exhibition).

Interestingly, the influence of Ferguson’s “Walking and Thinking and Walking”—and of the artworks he brought together there—were recently given a retread in a “mimeographed” version of the show created by some graduate students at the Arizona State University Project Space in Phoenix.

While the “mimeographed” version of the show seemed depleted in many ways (stick-pinned versions of photocopied exhibition-catalogue pages and artist-bio printouts predominated) the students added a musical component to their small, redux version of “Walking and Thinking and Walking”—one that Ferguson says he wished he had included in the original show.

“The thing I probably would have done differently [for the 1996 show] is look for songs with the word ‘walk’ in the title,” Ferguson, who knew of and supported the new version, says. “I probably would have worked with somebody who knew more about music than I did, and done a soundtrack for it…. I think it would have added to the textural dimension of it [the show] and made it even more discursive than it was.”

On that playlist in Phoenix: “Walking After Midnight,” “Walking in LA,” “I Walk the Line” and many more. A copy of some dance steps were installed on the Arizona project-space floor in homage to Andy Warhol’s piece in the original 1996 show, while photocopies of install shots of Canadian Dominque Blain’s Missa—a sculpture comprised of 100 pairs of army boots seemingly marching in formation—were tacked to a wall. Some quotations on walking were also installed on the windows, as in the original show—but these quoted Solnit herself, rather than other thinkers, as Solnit had originally done in ’96.

The contrasting environments for the original “Walking and Thinking and Walking” in 1996, and its “mimeographed” version in 2017, also highlight a motif that served as seed for Ferguson’s original influential exhibition: that is, thinking about bodies in space, and the structures which direct, and redirect, them.

“It became clear to me [in developing the original show] that there was a very particular kind of Modernist architectural space [at the Louisiana Museum] which has lots of glass” Ferguson says. “When you are inside, you are constantly looking outside at the sculpture gardens, and when you are outside, you are constantly looking inside.”

So the show was, first, “spurred by the idea that as you were walking you were being choreographed by the architecture, by the landscaped space,” and second, by the idea that there were two spaces, “each of them frustrating the other, to a degree…you always felt like you were on the wrong side of the glass.”

For Ferguson, the theme of art and walking, reworked, still has relevance—particularly when thinking about bodies in space, dealing with technologies and constraints of various kinds.

“Dancing is still this very difficult thing to do with our bodies, despite the fact that it seems ubiquitous,” Ferguson says of the Warhol piece, by example. “It’s not actually easy. It’s a process in which the body is trying to control itself, but there is still something primal about it. It’s not ‘either/or,’ it’s ‘both and none.’”

When asked about how walking in art might be refracted in light of mass protests and mass migrations in recent years, he notes this is something Rebecca Solnit was writing and thinking about in the 1990s.

“When does walking become marching? When does walking become dancing?” he asks. “There are ways in which movements of bodies and feet do different kinds of things. Huge numbers of people walking can be different from an individual doing the same thing.”

Leah Sandals is the managing editor, online, of Canadian Art.

This story was corrected on July 16, 2017. The original suggested that Public Studio’s Bruce Trail hike was part of the Walking Lab. In fact, that hike is part of an independent and ongoing Public Studio project titled The New Field, and Walking Lab will be joining that hike for a section, with related event called “Cripping the Trail.”

What scaffolds, structures or supports exist for walking-based art and artists? Walking Lab is one; it organized Dylan Miner’s To the Landless: Visiting with Lucy and Emma in spring 2017. As part of this event, participants walked to anarchist Emma Goldman's old house on Spadina Avenue in Toronto. Photo: Twitter.

What scaffolds, structures or supports exist for walking-based art and artists? Walking Lab is one; it organized Dylan Miner’s To the Landless: Visiting with Lucy and Emma in spring 2017. As part of this event, participants walked to anarchist Emma Goldman's old house on Spadina Avenue in Toronto. Photo: Twitter.