The MacKenzie Art Gallery debuts “Reflecting Dis-ease: eh ateh pahinihk ahkosiwin—Rethinking pandemics through an Indigenous lens,” an exhibition featuring works from its permanent collection, curated by Felicia Gay, Mitacs Curatorial Fellow, and Timothy Long, Head Curator.

“The question we have, really, is what sort of society do we want going forward, because COVID’s just a mirror.” This statement by mental health expert Dr. Kwame McKenzie from a recent interview on the CBC Radio program White Coat, Black Art reminds us that disease does more than just attack a person’s health; it represents a challenge to the way we live together as a society. Disease is also dis-ease, in that it encompasses not just sick bodies, but damaged psyches, relationships, and livelihoods. While the COVID-19 pandemic has stirred reflection about our societal ills in ways that seem unprecedented, this is not the first time that disease has changed the course of history. The four Indigenous artists in this exhibition, Ruth Cuthand, Robert Houle, Norval Morrisseau, and Edward Poitras, show how the pandemics that followed European contact decimated the peoples of North and South America and permanently changed the shape of life on Turtle Island.

eh ateh pahinihk ahkosiwin is a Swampy Cree term loosely interpreted as “sickness that is spreading to many.” The pattern and agency of transmittable diseases in Indigenous communities changed drastically after European contact, with Indigenous people having no immunity to newly introduced viruses and bacteria such as measles, typhoid fever, whooping cough, and, most devastating of all, smallpox. The colonial history connected with this last disease is the subject of Norval Morrisseau’s painting White Man’s Curse, Edward Poitras’ print Blanket and Robert Houle’s installation Palisade I. These pathogens made consistent appearances throughout the fur trade era and subsequent periods of economic expansion connected with land settlement and resource extraction. In Canada, many children died from disease as a result of the intolerable conditions at residential schools, where forced labour was a common practice, as well as during the Sixties Scoop.

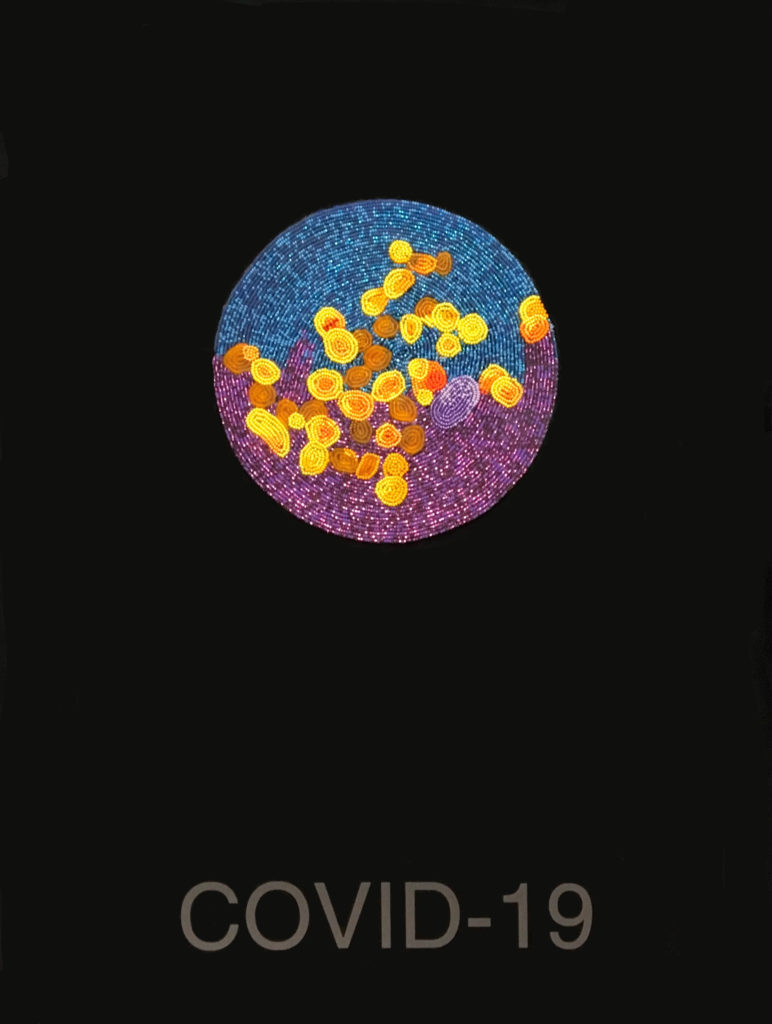

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, backing and thread, vinyl lettering on glass. Collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery.

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, backing and thread, vinyl lettering on glass. Collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery.