I think it’s important to start this story with a warning. As a resident of Canada, I feel like I’m on the outside of the Indigenous art scene in the United States, where cultural producers aren’t having the same conversations we are. We can wax poetic about being borderless nations, but it doesn’t change the differing canon, experiences and challenges of American Indigenous art scenes. My friend and colleague, writer and cultural historian Lou Cornum tells me that the Indigenous “scenes” in the US are different than in Canada. There, Indigenous communities still struggle to have conversations about recognition with American institutions, if they are recognized at all. The American nationalist ethos functions to erase diverse, adaptive and enlivened Indigenous life in the present, even more so than in Canada. I’m not bolstering projects of reconciliation in Canada, but I think it’s important to be honest rather than to exude performative politics in this retelling of what happened at the the 2019 Whitney Biennial opening on May 15, 2019. All this is to say that this review is influenced by my particular location and experience as an Indigenous person immersed primarily in Canadian art scenes. Already, through social media, through the NDN gossip highway, there are fractures in the story I’m about to tell.

I just couldn’t have imagined how real the militarization of American art industries would become for me and my kin that night.

I attended the Whitney opening with artist Kite, artist Dayna Danger, curator and art historian Adrienne Huard and artist and poet Arielle Twist, some of whom came to the Biennial on the invitation of artist and filmmaker Thirza Cuthand, who wanted to ensure that there was a Two-Spirit presence at the opening. My kin and I showed up dressed to the nines, as good Natives do, in leather, beads, pelts, faux fur, suede and regalia. This is how NDNs come into a space like the Whitney: with future-present fashion that honours ourselves, the space and all creation—and as if Creator was playing Snotty Nose Rez Kids’ “Boujee Natives” as our own personal soundtrack as we entered the venue. Because of the calls from community members for Warren Kanders to step down from his role as vice chair of the Whitney board, I anticipated at least a few enemies. I slathered my face in layers of war paint, bronzed and highlighted for cheekbones made in Creator’s image. Kanders is the owner and CEO of Safariland, a company that produces weapons and tear gas used at the US-Mexico border. Some might say that my use of the term “enemies” here is extreme. I don’t know what else to call someone who profits from the continued displacement and murder of Indigenous peoples.

Kite had the idea to bring blankets with us to honour the Indigenous artists in the Biennial—Nicholas Galanin, Laura Ortman, Thirza Cuthand, Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil, Jackson Polys, Jeffrey Gibson and Caroline Monnet—a shared custom between many of our communities. Kite stitched the names of the participating Indigenous artists into the blankets, which we purchased from a shop owned by a family we know in Kahnawake. We walked through the opening, each of us holding a blanket to be given to one of the Indigenous Whitney artists. As we moved through the space, we started giving them away, first to Monnet and Cuthand. We hugged, laughed and took pictures with each of the artists. And we felt like a war party of carefree NDNs on the run. Laughing, drinking, being silly, causing a ruckus and looking good all the while, just as our ancestors died for.

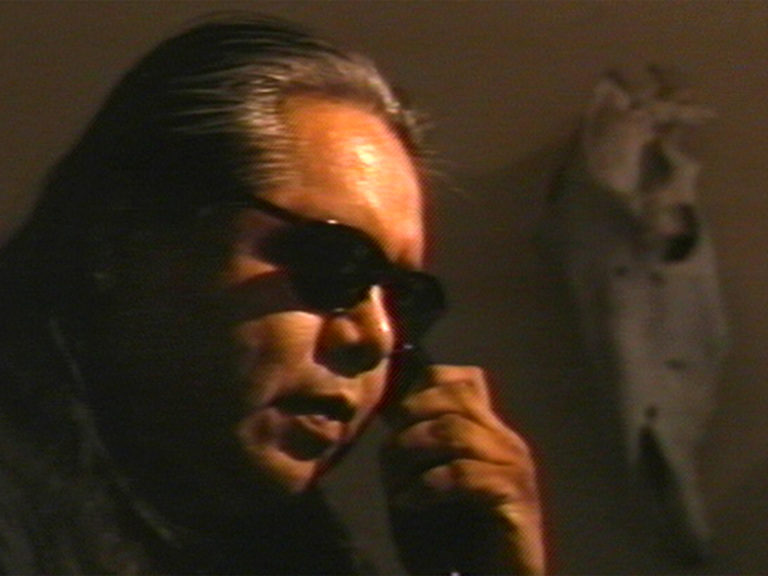

James Luna, The History of the Luiseño People (still), 1993. Video (colour, sound) 27 min 47 sec. Courtesy Video Data Bank at School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

James Luna, The History of the Luiseño People (still), 1993. Video (colour, sound) 27 min 47 sec. Courtesy Video Data Bank at School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The mood quickly changed when Danger and Kite laid down a sweetgrass braid for the recently deceased James Luna, in front of didactics bearing his name. Almost immediately the pair was surrounded by security guards who interrupted Danger whenever they attempted to explain what the sweetgrass was. He frantically spoke into his walkie-talkie for backup, as if we five Native femmes were the scariest security risk he had encountered in all his years on the job. We scuttled away, fearful of being kicked out and unsure of what had happened to the sweetgrass we had laid down for Luna. Suddenly the mood in the exhibition changed towards us. It seemed like whenever we moved into another room, without fail, two to five security guards would follow us and casually surround us on all sides. They seemed to have forgotten that Indigenous peoples have had their communities non-consensually militarized as a result of extractive legacies on their lands, and know well the subtlety of policing techniques. This was the first physical manifestation of militarization I felt at the Whitney that night. Of course, based on Kanders’s relationship to the Whitney, I knew I was entering a space that condones militarization, but I couldn’t have imagined just how real the militarization of American art industries would become for me and my kin that night.

The Whitney opening was so crowded I had a hard time looking at the art. Classic. I walked past a room full of people, and over the heads of the crowd I saw walls of clocks—a piece I now know is Agustina Woodgate’s National Times (2016, 2019). Woodgate installs the clocks in a “master-slave” configuration to show how the relationship between the “master” clocks and the “slave” clocks fall out of synch over time. In criticism I read about the Biennal, Woodgate is praised for exposing relationships between time, enslavement and labour. It’s true: the material analogy is spot on. But there’s also something vapid about the relationships depicted. Woodgate had thoughtfully arranged objects as stand-ins for real relationships and intimacies created by the transatlantic slave trade. I wondered where the actual people were that these objects referenced, so many of whom had been relegated to the position of “object,” to be bought, owned and sold during enslavement. Viewing National Times in the context of the Whitney Biennial confirmed for me that art functions in a world of ideas, as opposed to being an agent of measurable change and action. American audiences want artistic metaphors that are vaguely politicized. But who is overturning the violent cultures of the spaces and industries that house this apparently political art?

Thirza Cuthand, Reclamation, 2018. High-definition video (colour, sound), 13 min 11 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Thirza Cuthand, Reclamation, 2018. High-definition video (colour, sound), 13 min 11 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Why, in the era of #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and Standing Rock, are social calls and critiques still so stymied in the arts? For an industry that portrays itself as progressive in its proximity to radical ideas, why is art so unresponsive to the dynamics of power that define it, except in gestures of representation, gestures of representation and vague ideas of identity politics? Is it because we know Art can never truly be radicalized? Is it because the boards of art organizations are populated with capitalists who rely on ideas over people to ensure their profits? Certainly, there was a radical call in my early drive to seek out Indigenous art resistance. I came up in the streets, giving speeches at rallies and having my name grace CSIS files before I was even out of my youth. I came to art because I believe in its revolutionary, world-making power. However naive it sounds, I’m still matriculating through all these art world politics and ego trips. But this capital “A” art is something else altogether—this is an industry and a machine. A machine that, however uncomfortably, leads to the question of whether or not Indigenous Art, in the context of these industries, can ever truly be radical.

I think it’s important for us institutional NDNs to be honest. Is there ever ethical interaction with a space like the Whitney and a spectacle like the Whitney Biennial—within an industry such as Art? These are the kinds of conversations you have when confronting a machine like the Whitney and an institution and industry like American art. It’s the same kind of conversation I had with my kin when I realized that I spent more on an outfit for the Biennal than I ever had on a single outfit in my entire life, and when I reckoned that, perhaps, I began moving out of a space of precarity-driven activism to a secure footing within this complex industry that so loves to tokenize and decimate Indigenous life. That is my responsibility to acknowledge. Otherwise, even if Indigenous, am I not uncritically a part of this machine that tear gasses children at the border; am I not subtly condoning colonial violence?

Maria Hupfield and Regan de Loggans, two members of the Indigenous Womxn’s Collective, at Whitney Biennial 2019. Photo: Paul Walde.

Maria Hupfield and Regan de Loggans, two members of the Indigenous Womxn’s Collective, at Whitney Biennial 2019. Photo: Paul Walde.

As if anticipating my jaded line of questioning, curator Regan de Loggans and artist Maria Hupfield of the Indigenous Womxn’s Collective planned an action for the Whitney opening. When we arrived at the opening and met with Hupfield and de Loggans, they told us that their action would happen under Jeffrey Gibson’s hanging textile works. Fitting. Gibson’s works are a campy and chaotic, yet perfectly harmonious, marriage of materials: shimmering fabric is made sacred alongside colourful tassels, Indigenous weaving, quilting and protest banners that read “STAND YOUR GROUND” and “PEOPLE LIKE US.” The work commands a presence, towering in the air over the audience in huge dimensions. At the Whitney Biennial, much of the Indigenous artwork appeared hidden—many of the works only to be seen in a fall screening curated by Sky Hopinka. As one of the few Indigenous artworks actually present at the opening, Gibson’s sculpture brought complex Indigenous life, urban Indigenous life and myriad spiritual influences–from queer pop-culture to hip hop–into the Whitney that night.

The action began when de Loggans and Hupfield, who was wrapped in a banner, began blowing whistles and beating a drum loudly while circling one another. After a moment, de Loggans started unfurling the banner from around Hupfield’s body. The pair opened the banner, which read, “DEMILITARIZE OUR ART / PEOPLE OVER PROFIT.” Onlookers cheered and warrior called as de Loggans and Hupfield shook the banner. Security guards began to congregate, frantically communicating over their walkie-talkies and menacingly watching the action. De Loggans began beating the drum again and chanting with Hupfield, “disrupt, deconstruct colonial spaces,” as they continued circling one another. Eventually, Hupfield wrapped de Loggans in the banner as if it were blanket, and together they read a statement:

We, as Indigenous womxn and femme nonbinary people, are making a stand against the continued violence and oppression of brown bodies and communities. By not removing Warren Kanders from his position on the museum’s board, the Whitney is in allyship with white supremacy and genocidal settler colonialism. We are in opposition as Native artists, curators, and community members to the continued profit over people mentality. Indigenous peoples and other people of colour are violently under attack by Warren Kanders manufactured weapons of terrorism. You, the Whitney, is harboring a terrorist who profits from violence against brown bodies. You want our art, but not our people.

Hupfield and de Loggans had taken a great risk, and they continued chanting as they were swiftly asked to leave to premises. The effect of their intervention remained in the space after they had left, and the security’s actions toward my procession went from policing to menacing. We found ourselves menaced by audiences too, by reporters who crowded us for comments without divulging that they were reporters, and by so, so many random white women attempting to take our photo without consent. We were hounded for the rest of the evening by an art industry that wanted a piece of consumable Native resistance. Afterward, images of Indigenous activists, artists and community members at the opening proliferated across social media and art news sites.

My procession and I continued to mull about the gallery. Again I noticed the hidden aspect of the Indigenous art that night. For instance, Caroline Monnet’s video Mobilize (2015) was presented on rotation with a series of works by other artists, which took more than an hour to cycle through. Mobilize (2015) is an affecting video to watch, with an audio track that matches the intensity in tone and speed of a Tanya Tagaq song, and the intensity of the northern wild (and the city wild too). I was perplexed to see such a potent artistic vision relegated to a dark room in the far corner of the exhibition.

Laura Ortman, My Soul Remainer(still), 2017. HD video (colour, sound), 5 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Jeffrey Gibson, Stand By Me, 2018. Polyester organza, glass and plastic beads, printed chiffon, nylon ribbon, canvas, acrylic paint, repurposed artist’s paintings, PVC, artificial sinew, garment, (78 1/4 × 98 × 2 1/2 in.), Tipi poles (10 ft.). Courtesy Jeffrey Gibson Studio. Photo: Pete Mauney.

Caroline Monnet, Mobilize (still), 2015. 16mm film transferred to HD video (colour, sound), 3 min. Courtesy the artist.

Eventually we found Laura Ortman in front of her artwork. Ortman’s six-minute-long video of her playing the violin in the woods in New Mexico, sometimes with a cigarette in her mouth and at times accompanied by a dancer, was breathtaking. We gave Ortman her blanket and took more photos as security guards continued to crowd us—a reminder that we always find solace in one another when colonial institutions refuse us tenderness and police our very existence. We were now unable to move through the gallery without several security guards surrounding us. We began taking the security guards’ pictures, partially out of fear. We hadn’t even been a part of the action, but I guess being dressed in regalia is enough to criminalize you at the Whitney.

Where there seemed to be an invisibility to the Indigenous art at the Whitney that night, I also noticed a significant and recognizable Black presence. This is likely the result of differing cultures in the United States, where there has long been a pronounced history of Black resistance and presence in the face of white-supremacy. This is not to say that there exists no lineage of Indigenous intervention in the United States and Black activism in Canada (quite the opposite: these legacies are often rendered invisible). But I’ve noticed that the US suffers from an extreme marginalization of Indigenous communities that intentionally disappears said communities. To see us in our regalia that night was, for some spectators, like seeing the living dead. We looked good, but our Black colleagues and peers put us to shame. Dressed up in futurist queer fashion or cloths that referenced various cultural lineages, Black life flourished at the Whitney that night.

John Edmonds, Young man wearing a maternity bust (from the Makonde tribe), 2019. Digital silver gelatin photograph, 40 x 40 in. Courtesy the artist and Company, New York.

John Edmonds, Young man wearing a maternity bust (from the Makonde tribe), 2019. Digital silver gelatin photograph, 40 x 40 in. Courtesy the artist and Company, New York.

Agustina Woodgate, National Times(detail) , 2016/2019. Clocks, hardware, and sanding twigs, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Spinello Projects, Miami. Photo: Jesus Petroccini.

Agustina Woodgate, National Times(detail) , 2016/2019. Clocks, hardware, and sanding twigs, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Spinello Projects, Miami. Photo: Jesus Petroccini.

There was a significant inclusion of Black art at the Biennial, as well. And it seemed important to the artists that they contend with the anti-Black cultures of the institutions that housed them that night. Modernism and the power structures of the gallery were subtly but potently the punchline. Simone Leigh’s sculptures were concerned with the material representation of Black femininity through the use of non-European visual and material cultures representing African diasporic feminine spaces, communities and aesthetics in America. Stick is particularly jarring, made of ceramics to emulate a dress bodice boned in iron chains. Leigh is not here to let art industries forget the communities whose enslavement their ancestors, and thereby all institutions in the US, benefit from. John Edmonds’s photographs also caught my eye. From Picasso to Mapplethorpe, many a white boy has had a fetishistic and voyeuristic fascination with Black communities and called it fine art. This fascination is often tied up in an extractive love for “artifacts” such as African masks. The individuals Edmonds photographed defy the white-boy gaze. They activate masks and maternity busts, bringing them into a cyclical connection between past and present that disrupts the deadening voyeuristic gaze of white spectatorship, and avoids a fetishized representation of themselves and their cultural lineages.

At the opening night of the Whitney Biennial, I was coming to know this consumptive white spectatorship quite intimately, as another aspect of the militarized nature of American Art. Certainly, the actual policing was hard to bear. But there was also something intense about the majority-white audience present. Several times that I had to stop people from taking photos of me and my friends. It seems we unintentionally became some kind of spectacle for being dressed in regalia. White women would crowd us, holding their phones in front of them like some sort of barrier that is also an assertion of power, as if we were objects to be consumed—as if we were the art. We were, without a doubt, other. There was also the usual horde of white men in thousand-dollar suits who harassed my friends—the same security guards who had been following us around all night were then nowhere to be seen.

My kin and I left the Whitney dazed. Reflecting on the industries we had just witnessed, Arielle Twist asked me, thinking about the community-based, anti-institutional Indigenous art we know, we grew up on, and that we call home, “When does Indigenous art stop being weird?” I paused only for a moment and replied, “Probably when it gets to the Whitney.”

Nicholas Galanin, White Noise, American Prayer Rug, 2018. Wool and cotton, 84 x 120 in. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Craig Smith.

Nicholas Galanin, White Noise, American Prayer Rug, 2018. Wool and cotton, 84 x 120 in. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Craig Smith.