In 1967, Canada began seriously acquiring photography for its national gallery. Considering that critics date the birth of photography to the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, it is astonishing that it took well over 100 years for art professionals to take the medium seriously. In order to account for this loss, “The Extended Moment: Photographs from the National Gallery of Canada,” now showing at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, takes a longue durée approach to the history of photography. The exhibition comes to the Morgan from the National Gallery in Ottawa, where it was on view last year. The first part of the title refers to the exhibition’s organizing principle of historical juxtaposition. Curated by Ann Thomas, “The Extended Moment” pairs older work with more recent images, attempting to link the narrative of photography, from 1839 to the present, as one “extended moment.”

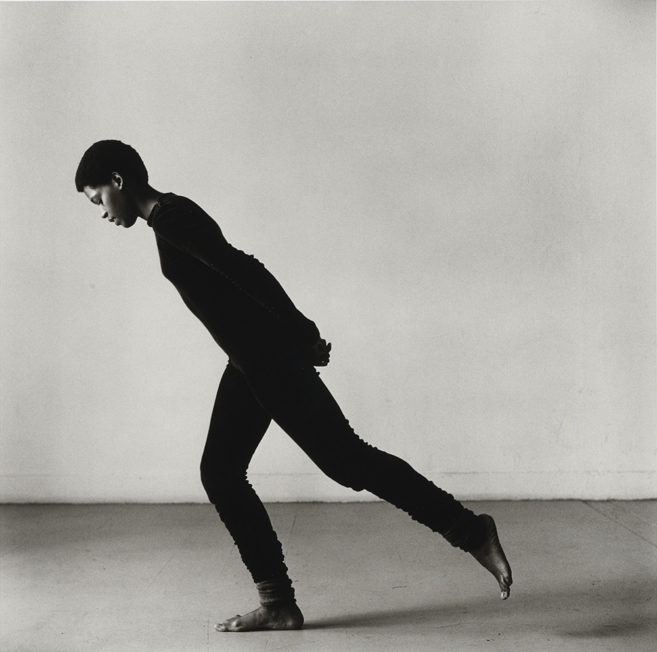

The photographs are selected from the National Gallery’s collection of over 200,000 works. The exhibition was thus overwhelmingly wide-ranging and included such disparate items as: 19th-century daguerreotypes; Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, which famously depicted the Great Depression; a Zanele Muholi self-portrait with her partner Valérie; a couple in their living room, from Diane Arbus’s nudist series; Alison Rossiter’s camera-less image created by developing expired photographic papers; and James Van Der Zee’s influential 1932 capture of a Black couple in raccoon-fur coats standing next to a Cadillac. On their own, each of these images carries a life-world—in the long strokes of a golf drive in the work of Harold Eugene Edgerton or Gordon Parks’s play with the metaphors of light and dark in Emerging Man—but presented together they become mere examples–artifacts in a taxonomy of photography as a discipline, cold objects or a representation of a problem.

The motivation behind these temporal juxtapositions (past is hung next to present)—however effortful the link by theme, shape or subject—is not as apparent as the curator might have hoped. The museum experience feels algorithmic, like scrolling through an online feed. Sure, some thematic connections are made accessible through the wall text, but they are not at all emotional—the sensuality and intimacy of photography’s direct capture is evacuated in such arrangements. Still, we all know, deeply, that some things are more urgent when felt.

Harold Eugene Edgerton, Golf Drive by Densmore, 1938, printed 1977. Gelatin silver print. Collection National Gallery of Canada. © Harold Edgerton/MIT, courtesy Palm Press, Inc.

Unidentified photographer, Portrait of an Unidentified Woman, c. 1850. Daguerreotype with applied colour. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Walker Evans, Church of Nazarene, Tennessee, 1936, printed later. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Phyllis Lambert, Montreal, 1982. Collection National Gallery of Canada. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gordon Parks, Emerging Man, 1952, printed later. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Lynne Cohen, Untitled (easel), 2007. Chromogenic print. Collection National Gallery of Canada. Estate of Lynne Cohen.

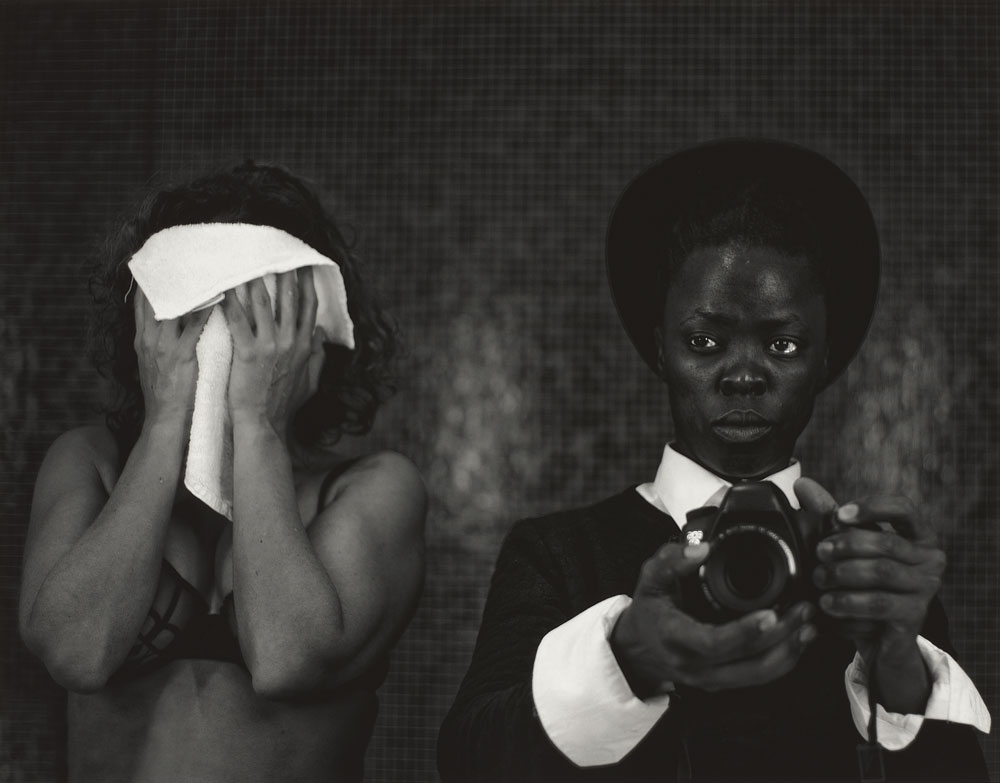

Zanele Muholi, ZaVa, Amsterdam, 2014. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist, Yancey Richardson, New York, and Stevenson Cape Town / Johannesburg. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Zanele Muholi, ZaVa, Amsterdam, 2014. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist, Yancey Richardson, New York, and Stevenson Cape Town / Johannesburg. Collection National Gallery of Canada.