In a letter dated November 2016, Iris Häussler writes to long-deceased painter Sophie La Rosière: “Having entered this room, trembling, I hid myself behind the mirror and looked through the cracked silver. It is this reflecting glass that separates worlds. While I watched you, one hundred years melted away, like a snowflake landing on warm skin.” It is with this intimacy that Häussler reaches back in time, speaking to a character of her own creation, with whom she has conjured a counterfeit archive of life and work.

Häussler is perhaps best-known for elaborate research-centred projects and enigmatic built environments, such as The Sophie La Rosière Project. Viewers acquainted with her work might initially be surprised with this exhibition, finding a spare selection of wall-bound pieces in a traditional white cube setting. Still, “Lost Gazes: Wax Works from the 1990s” explores similar preoccupations with concealment, absence and desire. (And indeed, the exhibition is concurrent with Apartment 5, which reconstructed the studio of La Rosière’s lover, Florence, for the 2019 Armory Show in New York.)

Häussler’s use of wax as a medium offers another through line between the earlier works and The Sophie La Rosière Project. La Rosière coated her paintings with black encaustic, in an act of simultaneous destruction and conservation, and all the works now on view at Daniel Faria are composed of fabric that has been similarly submerged and fixed in milky wax. The tactility of these objects is strange and seductive—the fibrous material is frozen in matter that is warm and soft, the fabric stiffened and suspended in ambiguous depths, the memory of its gentle movement forever preserved.

Another ambiguity in the translation of form: the works from the Lost Gazes series are made with curtains salvaged from abandoned houses and then cast into rectangular slabs corresponding to the windows from which they were taken. The creases and swirls of the tangled lace are entrancing, even more so when one considers the unknown figures who once stared back through the window glass, now turned opaque.

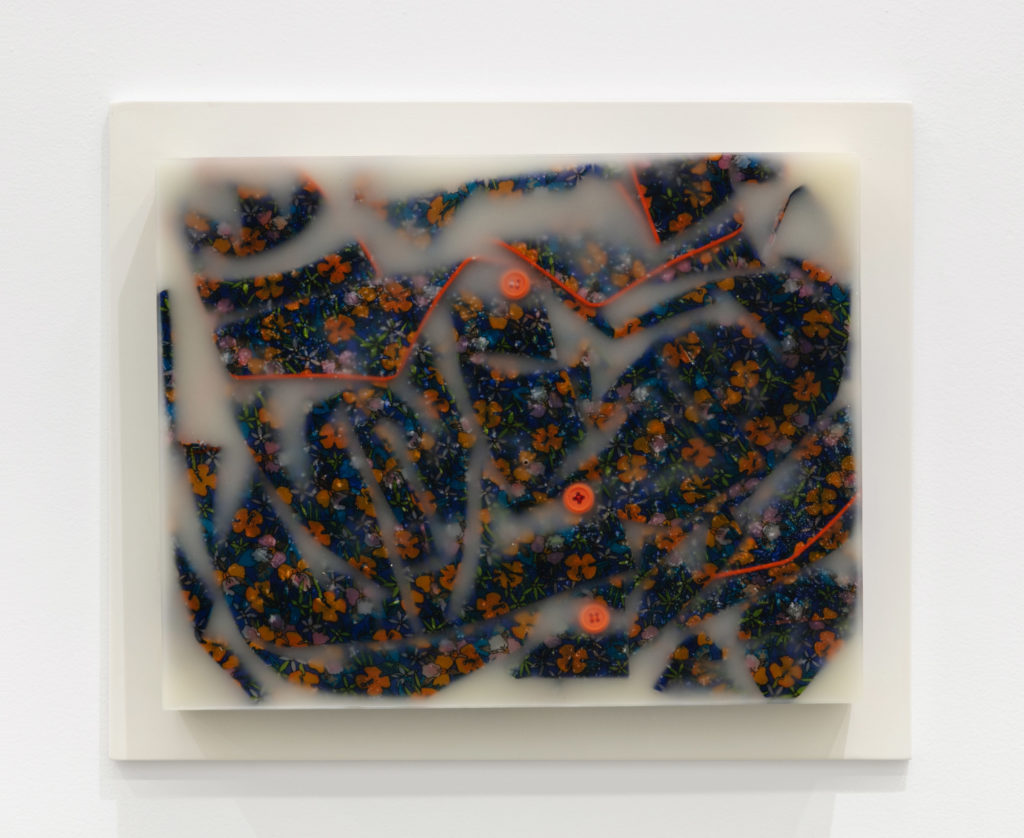

The exhibition also includes works—Schwester (Sister) and Mutter (Mother) among them—made from richly pigmented floral dresses crumpled and subsumed in colourless wax. The process of encasement brings petrified details, such as the stitching of a buttonhole, to the fore, like floral arrangements pressed into a book. Clothing conjures an essence of its absent wearer—both as a reflection of their taste and through its past proximity to their skin. Häussler named the works in this series for people in her family, which calls to mind the myriad complex relationships, both affectionate and discordant, among female kin. By working with the evocative material residue of her relatives, Häussler makes them active partners, rather than simply subjects, of her art-making. As individual objects of contemplation in an austere, minimal setting, Häussler’s wax works offer a beautiful experience: their mysterious tactility, without archive or testimony, invites viewers to linger with them as pure enigma.

Iris Häussler, Mutter (Mother), 1998. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.

Iris Häussler, Cousine des Vaters (Father’s Cousin), no date. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.

Iris Häussler, Verlorene Blicke (Lost Gazes) , 2000. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.

Iris Häussler, Verlorene Blicke (Lost Gazes) (detail), 2001. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.

Installation view of Iris Häussler, "Lost Gazes: Wax Works From the 1990s" at Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery.

Iris Häussler, Gross-tante (Great Aunt), no date. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.

Iris Häussler, Gross-tante (Great Aunt), no date. Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery, Toronto.