On June 14, 2017, the Vancouver Art Gallery announced the appointment of Vancouver-based writer and curator Tarah Hogue as “the Gallery’s first Senior Curatorial Fellow, focusing on Indigenous Art.” As is often the case, the news was already in circulation, and had been met first with declarations (“About time the VAG hired an Indigenous curator!”), followed by discussion (“Yeah, but what kind of budget will she have?”) and finally, dissection (“I hear it’s a limited term appointment—so let’s not get our hopes up”). Amid this tempered joy were speculations on how Hogue, who is of Métis and Dutch ancestry, might preface her coming program. Thirteen months later, Hogue has given us her overture—a question and a provocation—which might one day be understood as an index of what will follow: how do you carry the land?

Featuring artists Ayumi Goto and Peter Morin, with contributions from fellow travellers Corey Bulpitt, Roxanne Charles, Navarana Igloliorte, Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Haruko Okano and Juliane Okot Bitek, “how do you carry the land?” begins, appropriately enough, with its title—a question that asks what it is to carry that which the carrier walks upon. A riddle for some, a reality for others, the question evokes a range of responses. Most immediately, it offers a recognition that the land is not a static entity upon which to impose arbitrary form, as anthropologist Ralph L. Holloway Jr. famously proposed in his 1969 definition of culture, but rather an active, even pedagogical medium that, as scholars from Jeannette Armstrong to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson remind us, informs through its own life-giving, dialectical force.

Another response to the title came on opening night. Following remarks that included a welcome song by Chief Bill Williams of the Squamish Nation, a land acknowledgement by VAG Director Kathleen Bartels and introductory words from Hogue, Goto and Morin beckoned patrons up the rotunda stairs to the third floor. Once assembled, Morin sang and drummed a Tahltan welcome while VAG staff handed out noisemakers (den-den daiko in honour of Goto’s Japanese ancestry and rattles in honour of Morin, who is Tahltan). In recognition of the building’s history as a former provincial courthouse, Morin asked the crowd “to make enough noise to invite all of the ancestors who have never felt welcome in this building—into this building.” Following a glorious roar (and its encore!), Goto and Morin invited participating artists to stand with them for two voice-and-drum songs by L’Hirondelle, who is of Métis/Cree–non-status/treaty French, German and Polish descent. “Language is really important to me,” she said, “because I think that when you say ‘how do you carry the land?’—we carry it with language.”

The irreducibility—if the not the indivisibility—of land and language is echoed in Haruko Okano’s ceremonial entranceway, which links the rotunda and the exhibition space. Adorned with found objects associated with the sea on one side of the entrance and the shore on the other, two worlds intermingled overhead, where a keystone might fit were this entrance an archway. Looked at another way, the two worlds (sea and shore) could be seen as emerging from a single source, only to distinguish themselves as pillars as they made their way to the floor. Indeed, given that Goto and Morin have discussed the importance of their mothers in relation to their lives and practices (part of the exhibition includes a private tour for their mothers), Okano’s entranceway is as much a place of birth and transformation as it is an adornment of an engineering and architectural necessity.

Structurally, the exhibition is comprised of three spaces. Inside the entrance is an area devoted to Goto and Morin’s close relationship—as friends, as collaborators and as commissioning anthologists. At the centre stands a low platform, which, after the opening night performances, became a resting place for objects/artworks (the den-den daiko and the rattles). Entitled Silheng Kwenkwem [Stand Strong] (2018), the weaving is made of red cedar bark, raffia, wool and synthetic yarns, and took many hands to produce, including those of Hayley Zacks, Will George, Feather Arnouse, Claris Figueira, Aron Jackson and the lead artist, Semiahmoo First Nation member Roxanne Charles. Beyond it: a vermillion-coloured wall that features gifts (and their stories) exchanged between Goto and Morin on one side, and on the other side, a video projection the pair made about the confluence of the Stikine and Tahltan Rivers, accompanied by recordings of their heartbeats. Nearby is a wall poem by Juliane Okot Bitek, composed and installed after the completion of the exhibition’s three performances, along with one of three free-standing masks by Haida artist Corey Bulpitt—this one of Hogue.

Ayumi Goto, Rinrigaku: Collected Responsibility, 2016. Documentation of performance. Courtesy the Artist. Photo: Yuula Benivolski

Peter Morin, Cultural Graffiti in London, 2013. Documentation of performance. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Dylan Robinson

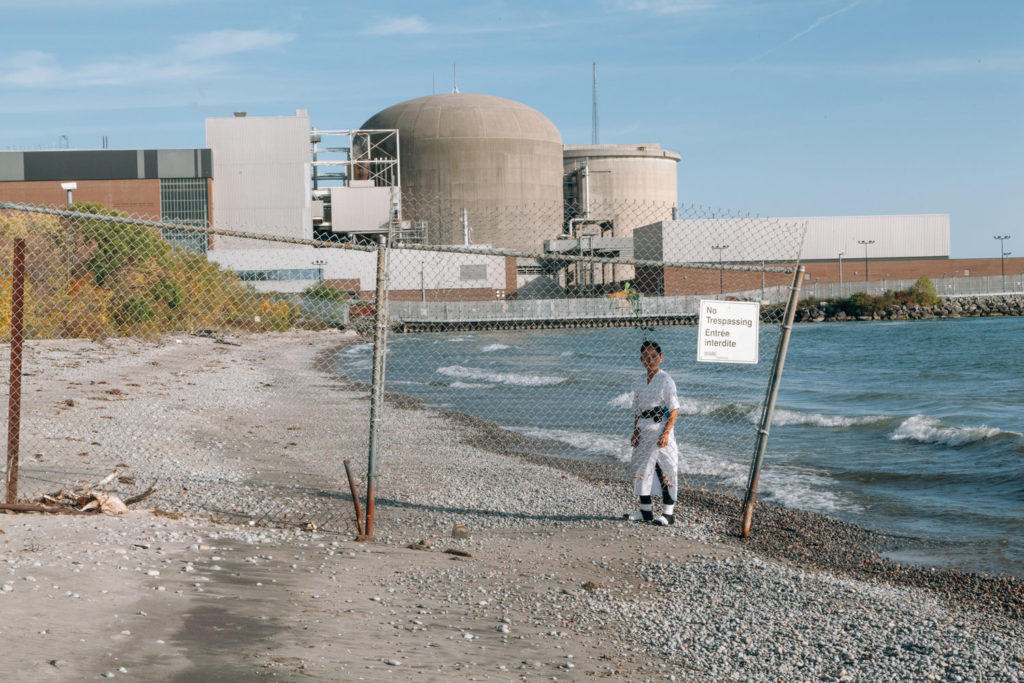

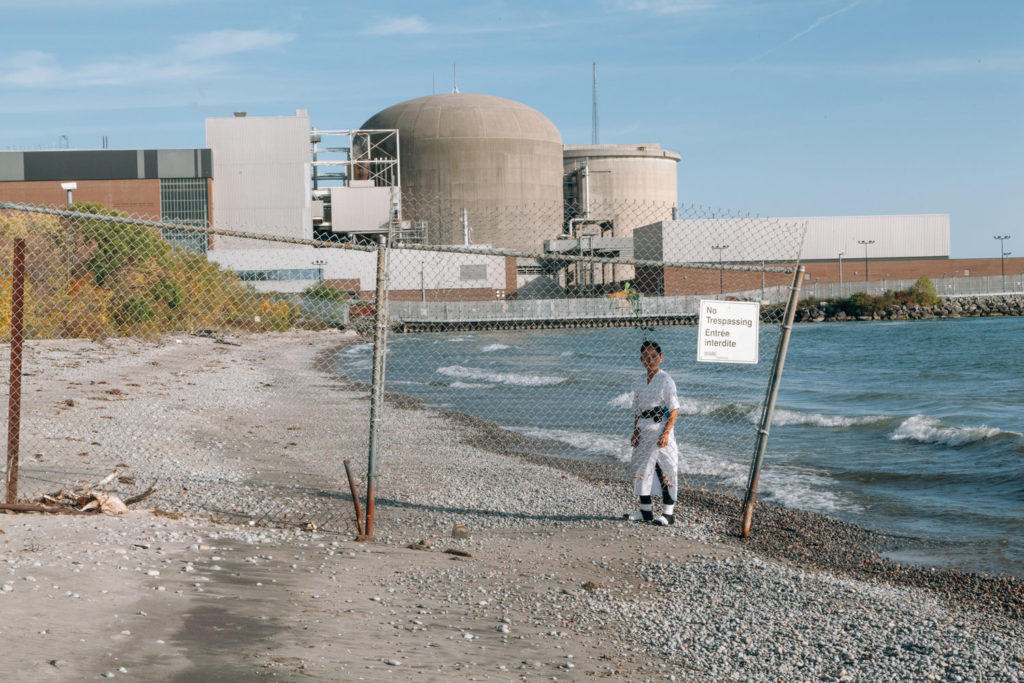

Of the other two masks, Ayumi (2018) stands in a room devoted largely to the work of Morin, to the west, and Peter (2018) in the room devoted largely to the work of Goto, to the east. Although performance documents dominate these breezy, uncluttered rooms (works include Goto’s La Jetée-like trespass at an Ontario nuclear plant and Morin’s impromptu performances at five police-protected landmarks in London, England), both include more self-conscious forms of object production, and both embody travel. In the large-scale, conceptual work in sonorous shadows of Nishiyuu (2013), Goto pays homage to Cree youth who walked from northern Quebec to Parliament Hill in support of the Idle No More movement by running 1,568.5 kilometres in 104 days and producing a watercolour painting and a diary entry after each of those days. In a serial work titled confronting colonial time: evidence of power/covered in the residential school (from the Before There Was Light: Experiments in Time Travel series) (2014–18), Morin gives us a horizontal row of seven boxes, each containing a blackened figurine paired with a found clock.

But it is performance works for which Goto and Morin are best known, and so it is that the highlights of this exhibition came during its attendant performances—the most notable of which (this is not us) took place on July 21. Here, Hogue arranged for VAG conservator Tara Fraser to cut the security cord that attached the masks of herself, Goto and Morin to their armatures, allowing them to be carried on the faces of their namesakes throughout the building and over its grounds. It is difficult to put into words what a gesture like this meant to those gathered. For this viewer, the mere presence of scissors in relation to Goto and Morin’s nearby Hair (2013) recalled the traumatic legacy of Indian residential schools, and by extension, a Vancouver Art Gallery that acknowledged its own colonial legacy when it announced Tarah Hogue as its “first Senior Curatorial Fellow, focusing on Indigenous Art.”

Ayumi Goto, Tarah Hogue and Peter Morin, this is not us, 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

Ayumi Goto, Tarah Hogue and Peter Morin, this is not us, 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

Ayumi Goto, Tarah Hogue and Peter Morin, this is not us, 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

Ayumi Goto, Tarah Hogue and Peter Morin, this is not us, 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery