In Halifax, we are currently seeing many artists changing and shifting their roles when it comes to presenting and making work, and encouraging more public participation.

Granted, public engagement in art is not a new thing, nor are the artists currently enacting it in Halifax claiming to be inventing it. However, in an art world that many can experience as claustrophobic and rigid, public engagement can shift conversations of elitism, classism, ableism and race.

This shift, this push, this change, is what we see happening (or about to happen) in Halifax with artists such as Carrie Allison, Willow Cioppa, Maria Hupfield, Raven Davis, Ursula Johnson and Amy Malbeuf.

Carrie Allison, a NSCAD MFA student of Cree/Métis and settler descent, has begun, through her work, a process of reclamation; in it, she activates ancestral history lost through the Canadian colonial system. “My maternal family hails from High Prairie, Alberta,” states Allison. “For the past year, I have been incorporating beading into my artistic practice as a way to become more familiar and comfortable with my maternal ancestry.”

For Allison’s thesis project, she has started to bead the patterns of two rivers she feels connected to: the Heart River in Alberta and the Fraser River in BC. “These rivers are important to me and to my ancestors,” Allison says. “I look at the history and practice of beading as an act of respect and honouring; by beading these rivers, I am honouring the ancestors’ gifts to us.”

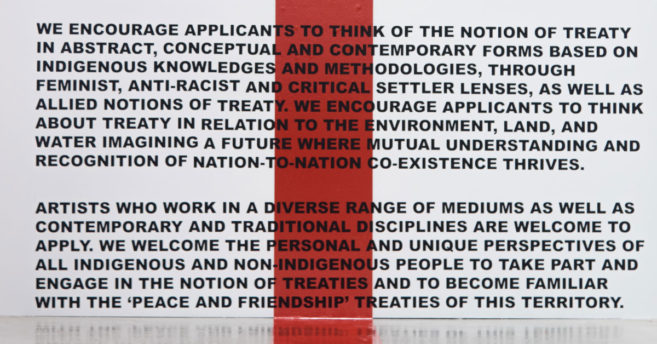

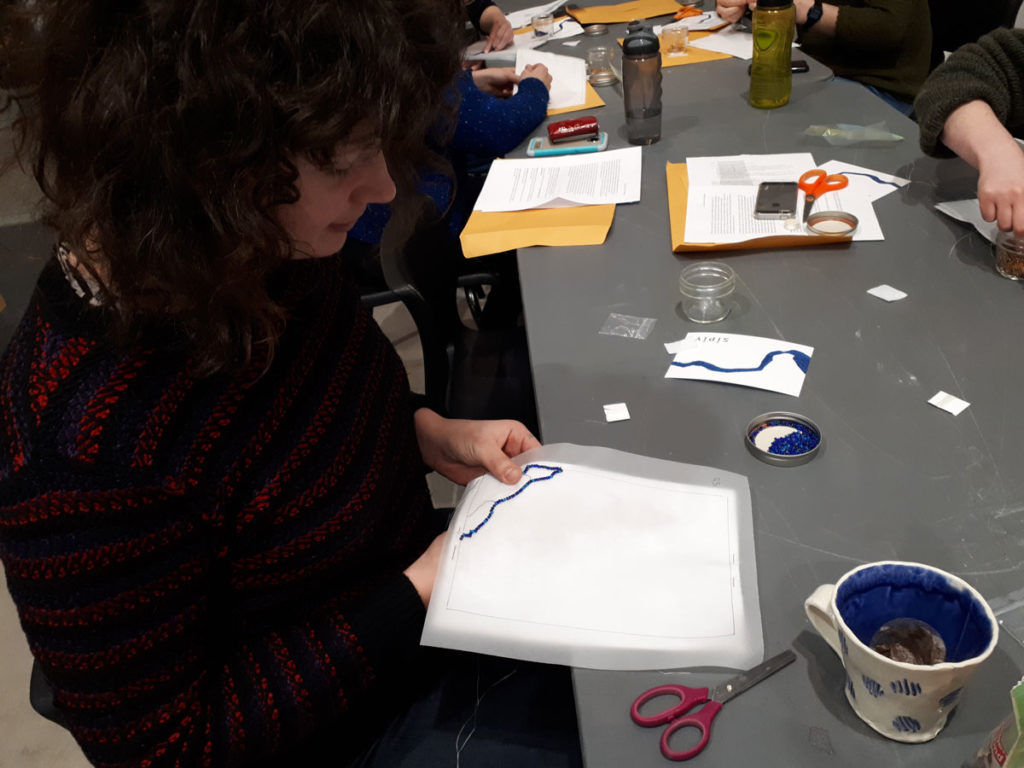

Carrie Allison’s Beading Shubenacadie River workshops at Treaty Space Gallery in Halifax involve collaborative work on mapping an important Mi’kma’ki waterway. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Carrie Allison’s Beading Shubenacadie River workshops at Treaty Space Gallery in Halifax involve collaborative work on mapping an important Mi’kma’ki waterway. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Allison, with members of the public, is also currently beading one of the most important waterways here in Mi’kma’ki—the Shubenacadie River—to honour the space she has called home for the past seven years. Beading the Shubenacadie River is also politically important for Allison and her collaborators, as the river has been under threat; Alton Gas has proposed to create two salt caverns in order to store natural gas, resulting in huge quantities of salt brine to entering the river. With this much salt brine, there is a risk of destroying the natural ecosystem of the river and everything that relies upon it.

Allison’s Shubenacadie River workshops invite locals (of all skill levels) to take part in beading different patterns of the river with assistance and materials provided by the artist. “This project is meant to honour the river with many hands,” says Allison.

One such beading circle/workshop recently took place on March 6 at Treaty Space Gallery at NSCAD’s port campus, with another slated March 13 from 6 to 9 p.m. There were other events in February, and there is also a possibility of more dates being added later. “These sessions give anyone an opportunity to ask questions about the project, receive a beading kit and learn to bead if they are a beginner,” says Allison. “These events are meant to be sharing circles; people can come together and share beading skills, as well as stories and thoughts around the history and plight of the Shubenacadie River.”

Willow Cioppa, a Zimbabwean-Italian artist based in Montreal, did a residency at the Khyber in Halifax based in care and actively engaged publics.

Willow Cioppa, a Zimbabwean-Italian artist based in Montreal, did a residency at the Khyber in Halifax based in care and actively engaged publics.

Willow Cioppa, a Zimbabwean-Italian artist based in Montreal, finished their residency with the Khyber Center for the Arts on February 24, with their residency exploring intersections of queerness, sexuality, poverty, blackness and femininity. During their time with the Khyber, Cioppa hosted two events: the first was An Intimate Evening of Poetry with Willow Cioppa and the second was A Workshop on Collective Care among Marginalized Communities.

“My residency focuses on the investigation of care among marginalized populations, visualized through a poetry comic book,” Cioppa writes in their artist statement. “Through this residency, my aim is to articulate how different intersections of oppression force individuals to not only nurture themselves, but to nurture those around them in a profound and engaging way as a radical form of protest.”

Cioppa’s inviting of the public into their workspace and their emphasizing of actively engaged publics for both their events is powerful—these gestures rewrite the script on care and creation of work and art. Cioppa’s work needs community participation, as healing for marginalized groups must come both from within and from without. To that end, the events led by Cioppa allowed for community members to share, listen and care for themselves and the group. Community-based work often relies on those involved to allow for vulnerability, which is where the aspect of care and nurturance that Cioppa stresses in their artist statement comes in.

By inviting communal engagement into their residency, Cioppa enacted what their artist statement states: a focus on care. Sharing in semi-public spaces like the Khyber can be a vulnerable experience, but Cioppa ensured that care was the focal point for the community brought in. One is always taken care of when sharing Cioppa’s space, and the investigations of identity and related discussion are done, as well, through care. In this way, the public become members of the residency, acting in part as artist and art as they assisted in Cioppa’s workshops as well as in achieving the residency’s purpose.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,“ 2017. Installation view at the Power Plant. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,“ 2017. Installation view at the Power Plant. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Opening on March 17 at the Mount Saint Vincent Art Gallery, Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield’s “The One Who Keeps on Giving” revives the artist’s relationship with her immediate family, emphasizing the notion of kinship and connection. Beyond that theme, audiences are welcomed to actively bear witness, to actively listen and see and hold space.

The project’s installation—which debuted at the Power Plant in Toronto in 2017 and has toured elsewhere, too—will display two filmed performances by Hupfield and her siblings, along with a painting by the artist’s mother of Georgian Bay. Additional pieces of handmade felt objects such as boots, mittens and a canoe will be displayed accompanied by videos animating the objects in performance. The opening of the exhibition will happen alongside a performance within the gallery space by Hupfield as well as Anishinaabe artist Raven Davis, Mi’kmaq artist Ursula Johnson and Métis artist Amy Malbeuf. The performance will call upon trust and support between Hupfield and the other artists, with all performers sharing the space and activating selected works of Hupfield’s from within the installation.

This performance will ask audience members to bear witness to the artists as they move throughout the gallery, interacting with each other and the gallery itself. Bearing witness can also be understood as another form of communal engagement, asking audience members to be actively participating in listening and viewing the work in front of them in a way that is more intimate and connected than just watching a work “begin” and “end.” And this act of bearing witness also challenges the colonial gallery space and the rules of such, activating those watching the performance as not just “audience” but as members in what is happening; the witnesses and their witnessing feeds the performers as they all share the space together.

Gallery-goers in Halifax have an increasing ability to engage with artists and their works in more personal ways, sharing the role of maker or having the ability to bear witness to performances. These roles should not be taken lightly; sharing in the work requires vulnerability and intimacy, and labours both physical and emotional. I look forward to more Halifax art appreciators taking part in community-engaged work—changing the role of artist and pushing back against the rigidity of who, exactly, gets to claim that title.

Emma Steen is currently finishing a degree in art history with a focus on Indigenous art histories and visual culture at NSCAD University.