Before “David Milne: Modern Painting” opened in Vancouver earlier this summer, the show’s iteration at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery was met, at times, with aggressive criticism. Most notably, Jonathan Jones writing in the Guardian was loudly displeased: “One of Canada’s greatest painters? Come off it!” The Vancouver Sun’s Kevin Griffin agreed, and proclaimed it the kind of exhibition that “gives painting a bad name.” Despite this reception, Milne is often the subject of national praise here in Canada, regarded (in hindsight) as a worthy contemporary of the Group of Seven. Judgements of value, especially when looking at art by a canonical figure like Milne, often come down to some supposedly objective quality of “good” or “bad.” But with Milne this tendency arguably misses the point, though the polarized responses from critics are fitting: the through-line of the exhibition is embodied in the presence of a constant tension—on the canvas, in the subject matter, and in the show’s reception.

One of the most interesting aspects of Milne’s work is the evidence of international influence. In Drift on the Stump (1921), Milne carried out experiments of light and time, following Claude Monet’s Haystacks series (1890). Borrowing from the Impressionists, Milne abandoned local colour in service of a more subjective form of perception, as in his Interior with Paintings (1914). Like Henri Matisse, he embraced colour over line and, in 1913, five of Milne’s paintings were included in the Armory Show, which also included Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911). After that exhibition, Milne’s work continued to develop in lockstep with his artistic contemporaries, celebrating an increasingly fractured, frenetic style of painting that wasn’t bothered by mainstream conventions of a work’s beauty.

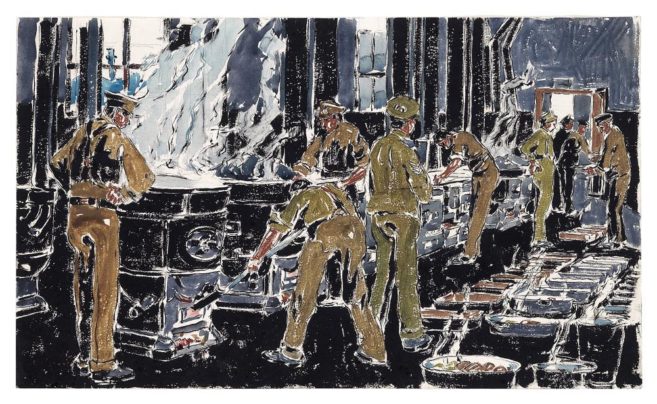

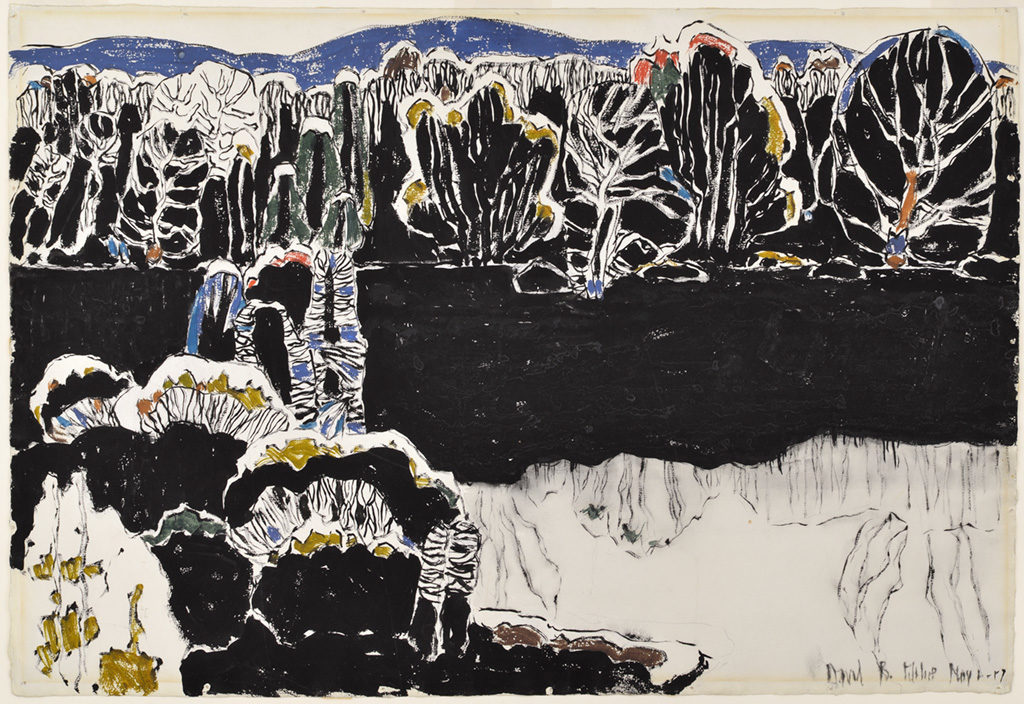

A decade before the Armory Show, Milne had moved to New York to study and work as an illustrator and graphic designer, only to become disillusioned and jaded by the commercially driven city. By 1916, he was convinced that he could survive only in the countryside. After leaving New York, Milne travelled as a war artist to the battlefields of the First World War, but missed the war itself, capturing instead the disastrous after-effects of mines, bombs and artillery on fields in France and Belgium. He returned to Boston Corners, New York, and then in 1929 moved to Temagami, in northern Ontario, where he chose to live and work in poverty and isolation. Both overseas and in Ontario, he painted his surroundings. “David Milne: Modern Painting” juxtaposes these points, capturing the vastness of Milne’s shift as an artist. His visual idiom progressively underwent processes of reduction and abstraction through experimentation, until nothing beyond the necessary was present in his canvases, as in The Twins Crater, Vimy Ridge (1919). Notably, the war paintings he created, ahead of his time spent on the actual battlefields, were formally similar to his colourful, vibrant paintings of New York.

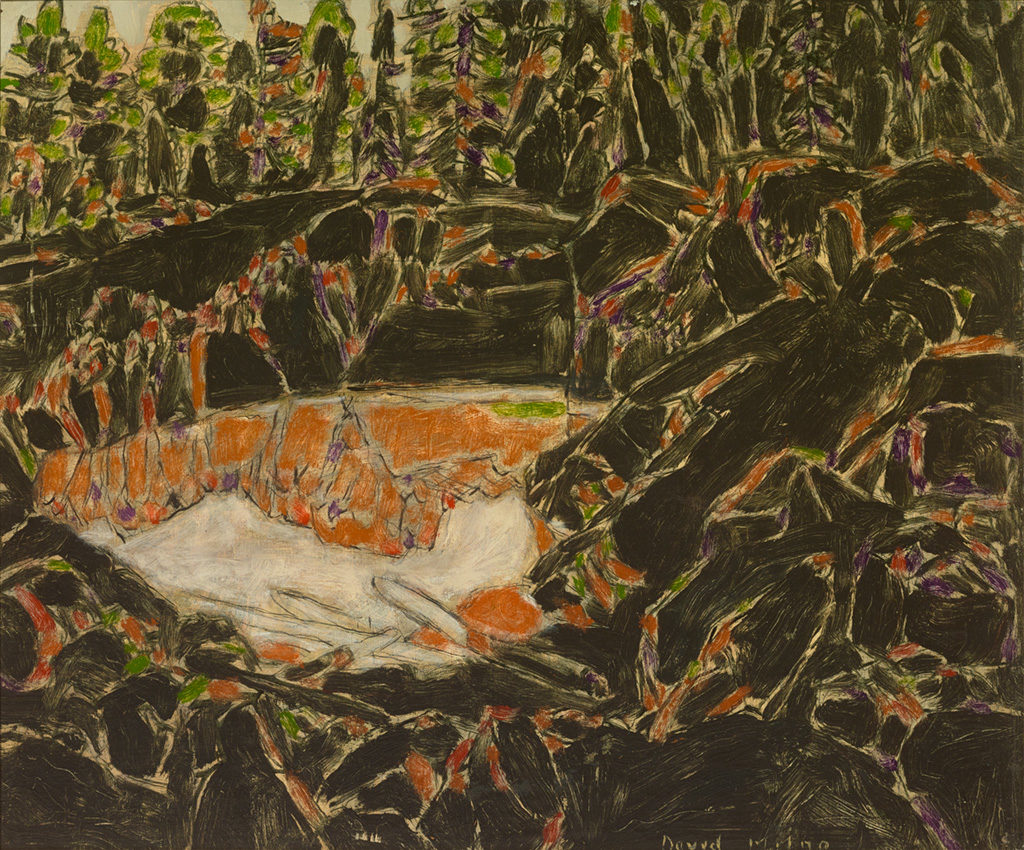

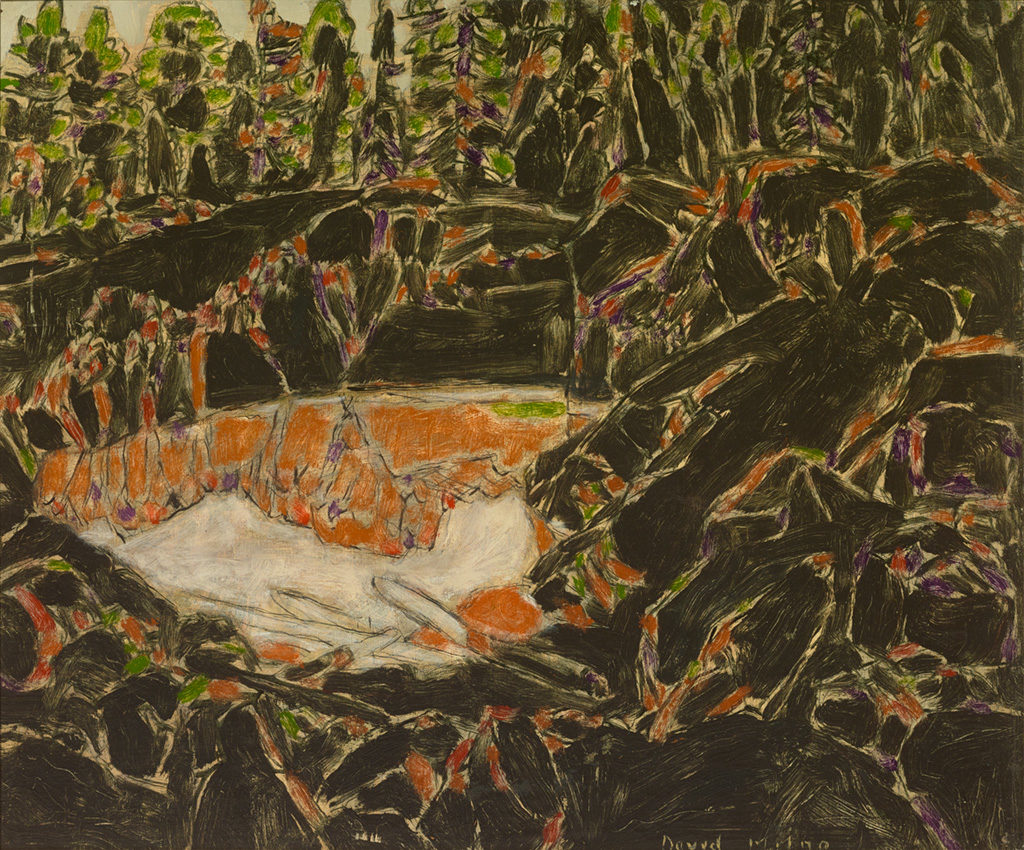

The paintings he produced after returning to Canada feel grim. He worked mostly in muddied blacks and browns, preoccupied with soil and mine runoff, and he created elaborate abstractions of the backcountry: white waterfalls, collapsed mine pits, dark reflective lakes. In all these tensions—between time spent in Canada and England, between war and peace, between life in New York and Temagami, between light and dark, colour and line—his oeuvre creates a portrait of the artist himself. His was a mind through which international visual idioms and Eastern Canadian wilderness coalesced into a Canadian modernism, important for its uniqueness and its innovation. As the exhibition’s co-curator, Sarah Milroy, noted at the opening, Milne, more than any other modern painter, taught her to appreciate the Eastern Canadian landscape—not by looking out over the horizon, but by looking straight down at muddied forest floors.

David Milne, Red Pool Temagami, 1929, oil on canvas. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery. Private Collection, Toronto. Photo Michael Cullen

David Milne, Painting Place III , 1930, oil on canvas. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery. Collection National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

David Milne, Reflected Forms, 1917, watercolour on paper. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery. Collection Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Women's Committee Cultural Fund

David Milne, Reflected Forms, 1917, watercolour on paper. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery. Collection Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Women's Committee Cultural Fund