“In space, no one can hear you scream.” So says the poster for the first, and most terrifying, of Ridley Scott’s Alien films. The same might be said of the countryside, which can feel as isolated and sinister as another planet. The allure of a cabin, isolation, is the same thing that makes it frightening—and “Cabin Fever,” a current exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, works hard to incorporate the varied and contradictory meanings of the cabin in popular consciousness.

Promising “a historical and cultural survey of the cabin in North America,” “Cabin Fever” gives you architectural models (17 of them), some (barely) historical artifacts, a few installations and quite a lot of writing on the walls. The exhibition follows the evolution of the cabin as if it was an exhibit in a natural history museum, replete with chronological info-decals. The curators do an admirable job of looking at the cabin from nearly every possible angle: as a colonialist outpost, slave quarters, utopian reverie, aspirational status symbol and an isolato’s dream. However, an over-reliance on everyday objects—there are several framed paperback books in the show, not to mention wall-mounted sweatshirts—give much of the exhibition the exact air of consumerist glee it is meant to explore. In one section, images from the influential Tumblr Cabin Porn are projected on a wall near interior photographs of cabin-influenced office design. Surely there is some better way to explore a collective yearning for simplicity than flashing pictures of the interior of Airbnb’s HQ.

Not surprisingly, the most successful aspects of the show are the least educational—Liz Magor’s Messenger (1996–2002) is a slick, eerie re-creation of a survivalist’s cabin, stocked with canned goods. One corner of the gallery is devoted to the grisly potential of the cabin—as a horror-film location or the hideaway of real-life criminals. Here, a montage of cabin-set horror films like The Evil Dead and Anti-Christ play in a darkened replica of a 1970s rec room. It’s very fun, and the sound of screaming teens echoes through the gallery.

In the end, this is a show doomed by the desire to cover all possible ground. Personally, I’m more interested in Lincoln, Montana—the site of Ted Kaczynski’s (a.k.a. the Unabomber) cabin—than I am in a well-preserved set of Lincoln Logs. “Cabin Fever” tries to cater to every taste, and in the end achieves only a gloss. It’s a bit of a miss that way—cabins are a lot of things, we learn, but glossy they are not.

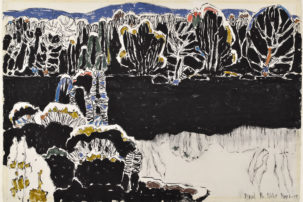

Installation view of "Cabin Fever" at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2018. Photo: Rachel Topham.

Installation view of "Cabin Fever" at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2018. Photo: Rachel Topham.

Installation view of "Cabin Fever" at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2018. Photo: Rachel Topham.

Richard Johnson, Ice Hut #556, Cochrane, Ghost Lake, Alberta, 2011. Courtesy the artist.

Scott & Scott Architects, Whistler Cabin, Whistler, British Columbia, 2016. Courtesy Scott & Scott Architects.

Douglas Cabin, Chewelah, Washington (measured drawing; detail), 1936. Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Cabin in Bracebridge, Ontario, 2016. Photo: Sam Barkwell.

University of Colorado, College of Architecture and Planning, Colorado Building Workshop, Outward Bound Micro Cabins, Leadville, Colorado, 2015. Photo: Jesse Kuroiwa.

Rudolph Schindler, Bennati Cabin, Lake Arrowhead, California (floor plan), 1934–37. R.M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collection, Art, Design and Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara.

Henrik Bull, Flender Residence, Stowe, Vermont, 1953. Henrik Bull Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects, Cliff House, Tomlee Head, Nova Scotia, 2010. Courtesy MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects Limited. Photo: Greg Richardson.

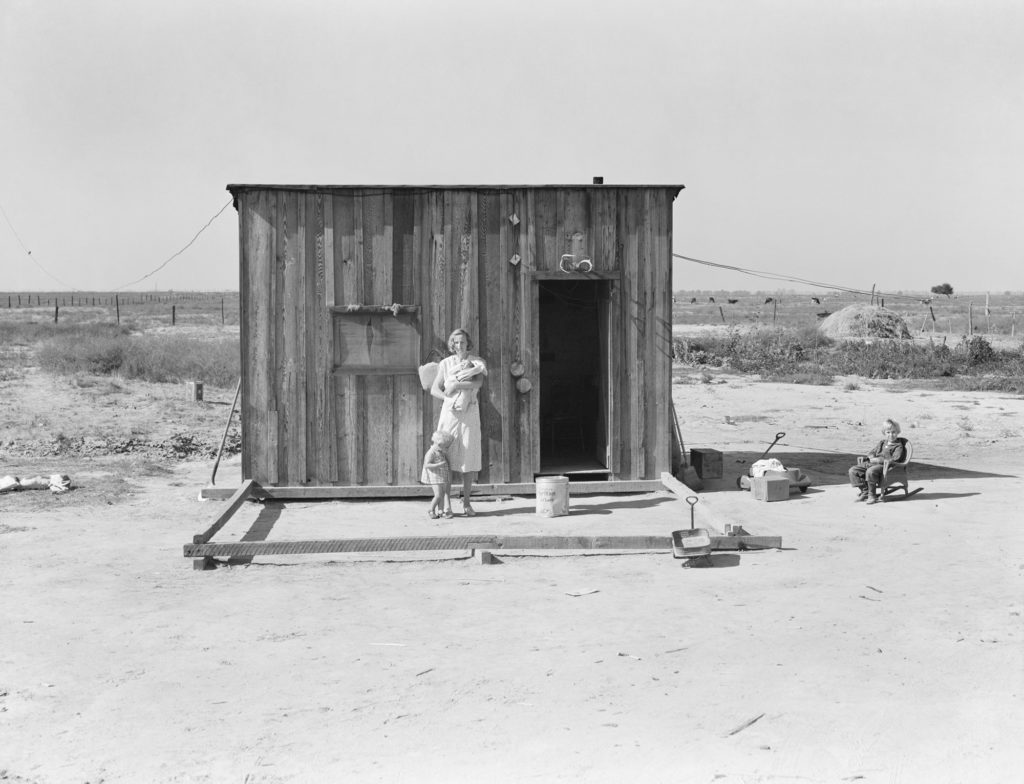

Dorothea Lange, Home of rural rehabilitation client, Tulare County, California, 1936. California Farm Security Administration–Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Dorothea Lange, Home of rural rehabilitation client, Tulare County, California, 1936. California Farm Security Administration–Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.