They’re artist-driven, they’re free to visit—and they’re so essential to Canada’s arts ecology that the National Gallery of Canada started a special prize for them last year.

Yet artist-run centres are unevenly put at risk, advocates say, by the COVID-19 crisis.

“The fact that less than half [of the artist-run centres in Canada with visual arts mandates] are core-funded by the Canada Council for the Arts continues to create a sort of inequity between organizations that have been around for a long time with stable core funding, and those that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s,” says Anne Bertrand, director of the Artist-Run Centres and Collectives Conference (ARCA).

Bertrand points to a new ARCA survey showing that “more than one-third” of artist run-centres “indicated having concerns of a financial nature” due to COVID. Some projected losing 10 to 25 per cent of earned revenue and “were concerned about the long-term impacts of the COVID crisis on their organization’s financial stability and their future capacity to access funding,” too. And “organizations without operating (core) support were more likely to anticipate a higher loss of earned revenue.”

The Media Arts Network of Ontario (MANO) represents a number of smaller non-profit artist-centred organizations. It recently issued an open letter to Canada Council director Simon Brault about this problem.

“In the wake of pandemic shutdowns, long-standing social inequities have become more visible than ever, including those in the arts sector,” says MANO director Ben Donoghue in the letter. “While emergency measures rolled out to date have helped to stabilize some arts and culture institutions, high barriers to eligibility for emerging and unincorporated arts organizations have resulted in many groups being left behind.”

That leaves some artist-centred organizations paying artists, but not their own workers: “Relying on project grants, [these organizations] receive support to compensate artists for their labour at industry standard rates, but are not supported to adequately compensate their own staff, whose skills comprise the essential labour of care necessary for the success of any program,” Donoghue writes.

Advocates are asking federal arts agencies to consider how emergency COVID funding for the culture sector can reach all who need it.

“A vibrant and resilient arts sector is one that supports its organizations and workers at all levels of their development, not just those who are already established,” write Donoghue and other MANO letter signatories. In another, separate letter to Brault, Bertrand echoes that: “We are asking that you please consider small and fragile organizations as a priority in the granting of emergency funding.”

Talking to some different artist-run centres across Canada shows that, as ARCA and MANO suggest, these organizations are impacted differently by COVID—at the same time that many of them remain committed, even during a pandemic, to serving artists and their practices in fresh ways.

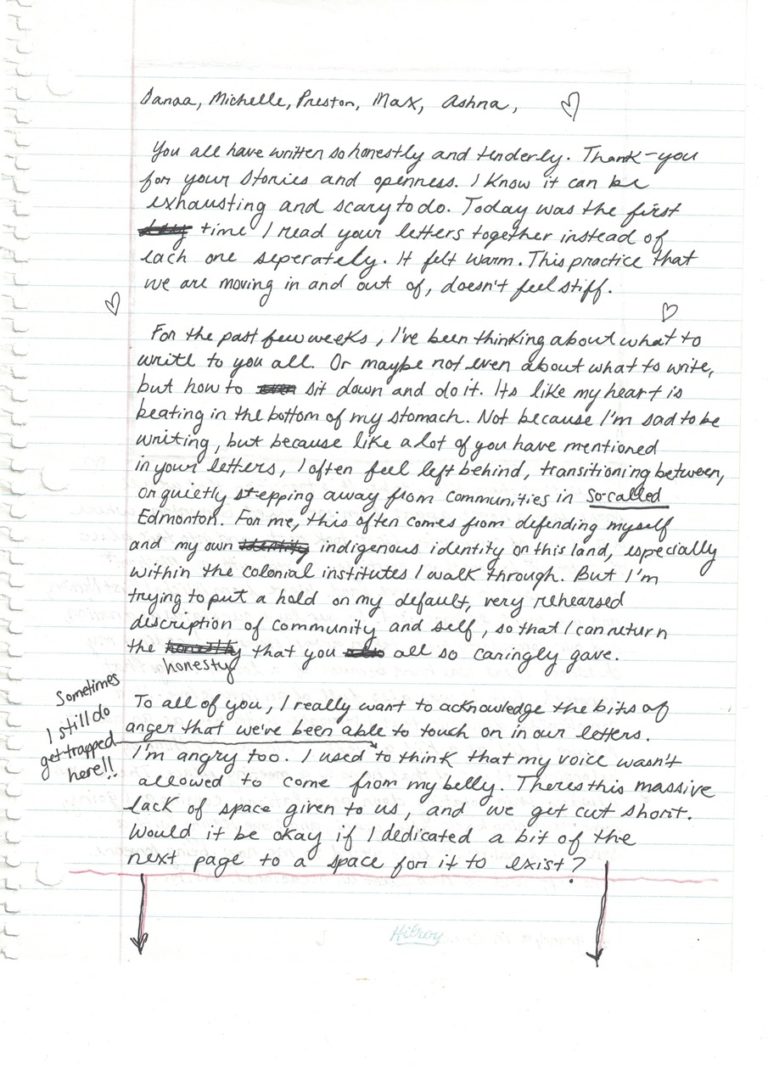

Kiona Ligtvoet wrote this March 21 letter as part of a project Latitude 53 and the Mitchell Art Gallery expanded during the shutdowns.

Kiona Ligtvoet wrote this March 21 letter as part of a project Latitude 53 and the Mitchell Art Gallery expanded during the shutdowns.

Musician Matthew Cardinal during a peformance livestream with Latitude 53 on April 8, 2020.

Musician Matthew Cardinal during a peformance livestream with Latitude 53 on April 8, 2020.

Latitude 53 in Edmonton is one of Canada’s oldest artist-run centres, founded in 1973. Its experience shows that even artist-run centres which are well established and receive some stable core funding—but that also rely on other revenues—are feeling precarity right now.

“In Alberta, the shutdown in gaming revenues has impacted many non-profits, including artist-run centres,” says Michelle Schultz, executive director of Latitude 53. “Gaming revenue alone makes up 17 per cent of our total revenue.” Add to this the fact that Latitude 53 bookstore sales and in-person donations are seeing “a decrease around 70 per cent” right now, and that Schultz and her team “don’t anticipate being able to run our annual fundraising event, or at least in the same way.”

Provincial funding issues also generate some concern right now for Schultz. “There’s a general paranoia in the air about impending cuts to the arts” in Alberta, she says. Schultz points to the government’s sudden cancellation of a provincial project grant program as one recent example.

“There is concern about precarity around not only getting through the COVID crisis,” but also beyond it, Schultz says.

Yet Latitude 53 has at the same time seen success in shifting some existing programs online—like a letter-writing project and a Lauren Crazybull artist talk—and developing new programs, like an online book club with artist Karen Kraven or weekly Art from Here artist-studio visits.

The results have actually expanded the gallery’s reach locally and nationally. “What we have been thinking about is trying to create spaces for connection and not just consumption,” says Schultz, particularly because “artists in Edmonton have historically struggled with isolation from other artists in the community and isolation from other art centres in Canada.”

“I think COVID has fundamentally changed our relationships to the community, and how we think about access,” says Schultz. “I think these will reverberate through our programming in months and years to come.”

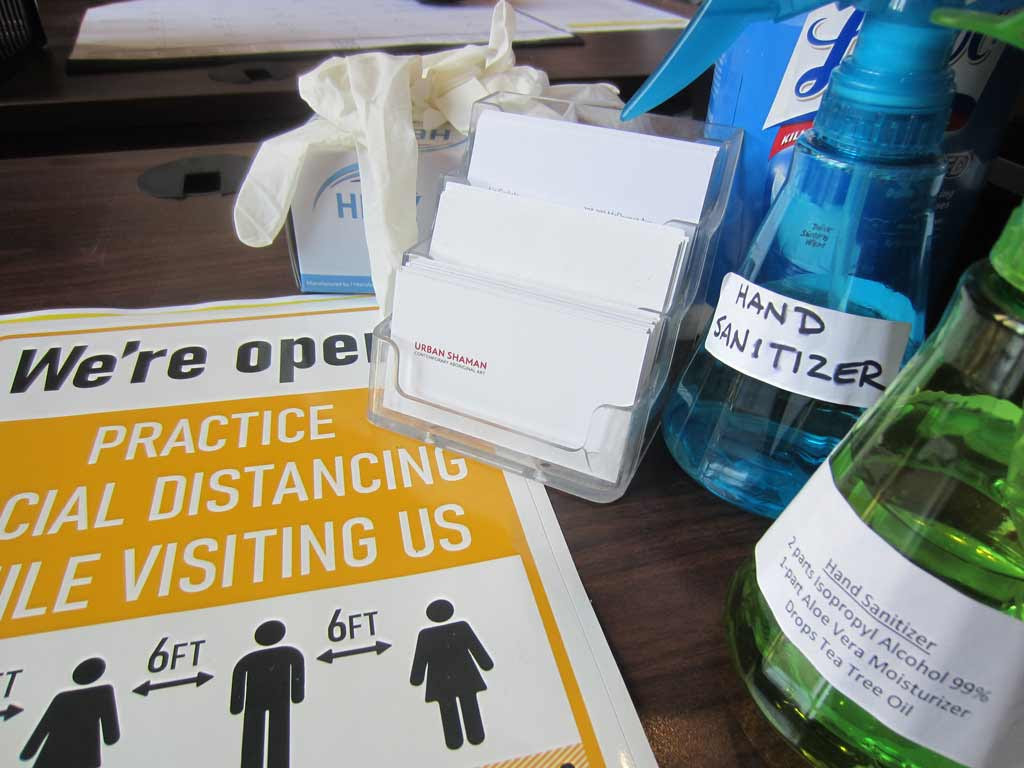

Urban Shaman is preparing to offer hand sanitizer and social-distance signage, among other measures, for its reopening on June 19.

Urban Shaman is preparing to offer hand sanitizer and social-distance signage, among other measures, for its reopening on June 19.

Elsewhere, artist-run centres that find themselves in a positive position financially thanks to solid core funding are concerned about peers who don’t have those same resources available.

“We are very fortunate,” says Daina Warren, gallery director at Urban Shaman in Winnipeg. “We are worried, of course, but because we have sufficient core funding, the main concern for us is more in terms of getting programming back to normal as things have been shifted or postponed… I feel bad about the organizations that may not have as much operating funding, that are going on a project-to-project basis, and that still have to keep things going.”

Given that a lot of project-based funding hinges on fulfillment of past or current projects, COVID-related postponements impact some organizations more than others, Warren notes: “If a project-funding-based centre has to postpone or cancel an event, how do they negotiate that?”

“What we have been thinking about is trying to create spaces for connection and not just consumption,” says one ARC director.

While Warren and Urban Shaman have had to incur some large incidental costs related to COVID—like a high-priced rush return ticket from the Sydney Biennale, where Warren was when shutdowns were announced, and a laptop for an administrator so they could work from home—these costs haven’t put the gallery at risk, because its core funding is stable at the moment.

Stability of funding, and the Province of Manitoba’s reopening schedule, have also permitted Urban Shaman to plan to open to the public June 19 to August 1 with the Vancouver Biennale’s touring show “Weaving Cultural Identities”—albeit with reduced gallery hours, a max-10-person capacity, installing disinfecting wipes, hand sanitizer and gloves to be at the entrance, and a suggested 45-minute time limit.

COVID still does, though, make it hard for this ARC to fulfill all its usual functions: “Can we do an artist talk virtually? Can we do a closing reception in August?” Warren wonders.

Urban Shaman was also in the midst of a website redesign when COVID shutdowns hit—a project that has gained new urgency in light of shifts to digital among many of the artists it serves.

“Watching the Indigenous artists, it seems like everybody’s been really prolific and productive from home—Zoom meetings are kind of out of control, but it’s been great to see.”

Artist Meagan Musseau’s work becomes body of water interwoven with territories beyond the sky (2020) on the Mount Pleasant Community Art Screen—a public-art site grunt gallery has been leveraging more since its main-space shutdown. Photo: Sebnem Ozpeta.

Artist Meagan Musseau’s work becomes body of water interwoven with territories beyond the sky (2020) on the Mount Pleasant Community Art Screen—a public-art site grunt gallery has been leveraging more since its main-space shutdown. Photo: Sebnem Ozpeta.

Uncertainty is definitely a watchword for the artist-run grunt gallery in Vancouver as well—sometimes in a beneficial way.

“For me the really persistent thread through this is there is just so much we don’t understand and we don’t know,” says program director Vanessa Kwan, “and we have all had to realign ourselves to this new reality.”

“At the gallery we are trying to take that to heart and are starting by coming up with programming that allows for a kind of co-learning,” says Kwan. “And because artist-run centres don’t have the same kind of numbers and admissions pressures as larger institutions, we have, to some degree, a tiny bit more flexibility.”

In grunt gallery’s case, programming during COVID has meant paying artists to do takeovers on Instagram, running a community #isolationhaiku series on its public art screen in Mount Pleasant and shifting overall to other kinds of public presentations. “We have been lucky to be able to funnel programs to the screen and online even though our gallery has had to shut down,” says Kwan.

At the same time, the ongoing crisis meant grunt had to cancel a big legacy-fund push for its endowment. So as to financial impacts, Kwan says, “we will have a clearer picture by the end of the year.”

Fresh flowers delivered by Hamilton Artists Inc. during a crisis-era fundraiser this spring.

Fresh flowers delivered by Hamilton Artists Inc. during a crisis-era fundraiser this spring.

Julie Dring, executive director of Hamilton Artists Inc., out on flower delivery for the fundraiser.

Julie Dring, executive director of Hamilton Artists Inc., out on flower delivery for the fundraiser.

Interestingly, some artist-run centres have surprised even themselves by being able to meld fundraising and community work during the COVID crisis.

“Rentals went down to zero” following COVID shutdowns, says Julie Dring, executive director of Hamilton Artists Inc. (also known as The Inc.). “We usually pull in up to a thousand [dollars] a month with that.”

To recoup lost revenues, The Inc. partnered with local greenhouses, which were experiencing a drop in business, to do delivery of handwritten messages with flowers in the local area.

“It was actually really successful,” says Dring. “We held the fundraiser twice, and quadrupled our revenue each time… It ended up being a good way for people to communicate with each other from a distance.”

Communication has also been a key theme of The Inc.’s approach to wider COVID-crisis arts resiliency.

“Something [we are] trying to do is stay really connected to the other arts organizations in Hamilton,” says Dring, citing “a circle of communication” set up early in the crisis between her and other arts leaders in the city in order “to pool together for advocacy for the arts in Hamilton if we needed to.”

One positive result of that circle has been the Hamilton Arts Council starting an artist relief fund, to which The Inc. contributed some of its programming monies: “It’s about supporting other arts organizations in the community and putting more of that money into artists’ hands directly.”

Artist Faune Ybarra creating the video work Thinking of you, railroad near 6th Ave. (2020) in Vancouver as part of her remote spring residency with Eastern Edge Gallery. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Artist Faune Ybarra creating the video work Thinking of you, railroad near 6th Ave. (2020) in Vancouver as part of her remote spring residency with Eastern Edge Gallery. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

At Eastern Edge Gallery in St. John’s, a shift to online has worked quite well in some ways. For instance, spring artists in residence Drew Pardy and Faune Ybarra were both keen to go virtual with their projects and workshops.

But it’s harder online to capture the way that artist-run centres can function as community hubs. “We are so used to constantly having visitors in the gallery—people from other arts organizations, artists and more. We are always cooking up new ideas and collaborations [face to face]. So now it is really difficult to maintain that,” says Daniel Rumbolt, interim director of Eastern Edge.

While Eastern Edge is doing some casual virtual drop-ins and talks, as well as the spring residency activity, staff remain wary of “Zoom exhaustion” and say they try not to expect too much of that platform.

Financially, Rumbolt confirms that the lack of receptions, events and rentals during the shutdown has led to a revenue drop for Eastern Edge.

Regarding the province’s COVID reopening plans, he notes that “even at level 1 there is no mention of allowing festivals.” That affects a contemporary art festival called HOLD FAST, which Eastern Edge is planning for end of September, “so we are trying to think about what we will do online—even though they have plans for different levels, we feel like we have to have six different backup plans, just in case.”

A certain mindset has helped amid the stress: “I think the biggest thing is that we need to have patience with one another and build patience with ourselves,” says Rumbolt. “I think in all our conversations with artists, we try not to go into it imposing how we think their project should adapt or change—it’s about having that open conversation and trying to remain as flexible as possible.”

The Unknown Future Rolls Towards Us (Future Fountain) (2019) is a work by Adam Basanta, one of the artists currently doing an at-home autoresidency with AXENÉ07.

The Unknown Future Rolls Towards Us (Future Fountain) (2019) is a work by Adam Basanta, one of the artists currently doing an at-home autoresidency with AXENÉ07.

After the shutdowns hit Canada, AXENÉO7 in Gatineau decided to create 20 “autorésidences” of $1,500 each rather than force a sudden digital-exhibition program.

“We really tried with this program to not instrumentalize the crisis—we really wanted to push forward art practices and find a positive out of a negative,” explain AXENÉO7’s director Jean-Michel Quirion and artistic assistant Mathieu Marleau.

The autonomous residencies are specifically designed for artists to work from their homes or their own studios during self-isolation, with the artists committing to present some of the work and practice over the coming months.

More than 300 applications were received for the residency; the 20 artists selected include Adam Basanta, Daniel Barrow, Valérie Kolakis, Maryse Larivière, Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, and Juan Ortiz-Apuy.

“With the shifts of many galleries and art institutions towards a digital or more web-based platform, we thought we could do something different and that’s where we went with the autoresidency,” say Marleau and Quirion.

But just as important, says Quirion, is that AXENÉO7 will continue, in the tradition of artist-run culture, to prioritize the needs of artists it already committed to. “It has been important to delay some shows [we had planned] because years and years of work has gone into them, and they are for practices not easily translatable online.”

What makes it all possible, in part, is the fact that AXENÉO7 receives steady funding. “We are really lucky actually we didn’t have financial problems,” says Quirion. “We get funding from Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, Canada Council and the Ville de Gatineau. When the crisis hit, we were able to account for all our activities.”