In downtown Edmonton this week, amid a big opening party at the new Royal Alberta Museum, is a small, much-needed permanent exhibit on residential schools—and the traumatic effects that have resounded through generations of Indigenous people. Though this small exhibit, located within the larger museum, may have been overlooked by many visitors during the building-launch festivities, it is a vitally important project.

“Art is what saved me in those residential schools.” This is what senior Dene Suline and Saulteaux artist Alex Janvier, based in Cold Lake, has said about his decade at Blue Quills in Alberta. Janvier’s double-sided canvas Blood Tears (2001)—which has one of his iconic paintings on one side, and a handwritten list of losses suffered by the children who experienced residential schools on the other, is one of the centrepieces in the new exhibit. The composition on the painted side, in addition to bearing the elegant abstracted shapes for which Janvier is renowned, also includes imagery of a cross atop a brick-red building, and the form of a single leg splayed upon an abstract ground.

The exhibit, located in the centre of the RAM’s Human History Hall, also includes a video of Janvier talking about his life and artwork, and features a variety of museum-collection objects. “He is so brave,” says Edmonton artist and University of Alberta professor Tanya Harnett of Janvier. Harnett, who is a member of the Carry-The-Kettle First Nations in Saskatchewan, was part of an advisory panel to the museum. “Without him I wouldn’t be able to do this,” she says of advising the museum on this and other displays. “Because he is doing it, I can do it.” Harnett notes that three generations of her own family attended residential schools.

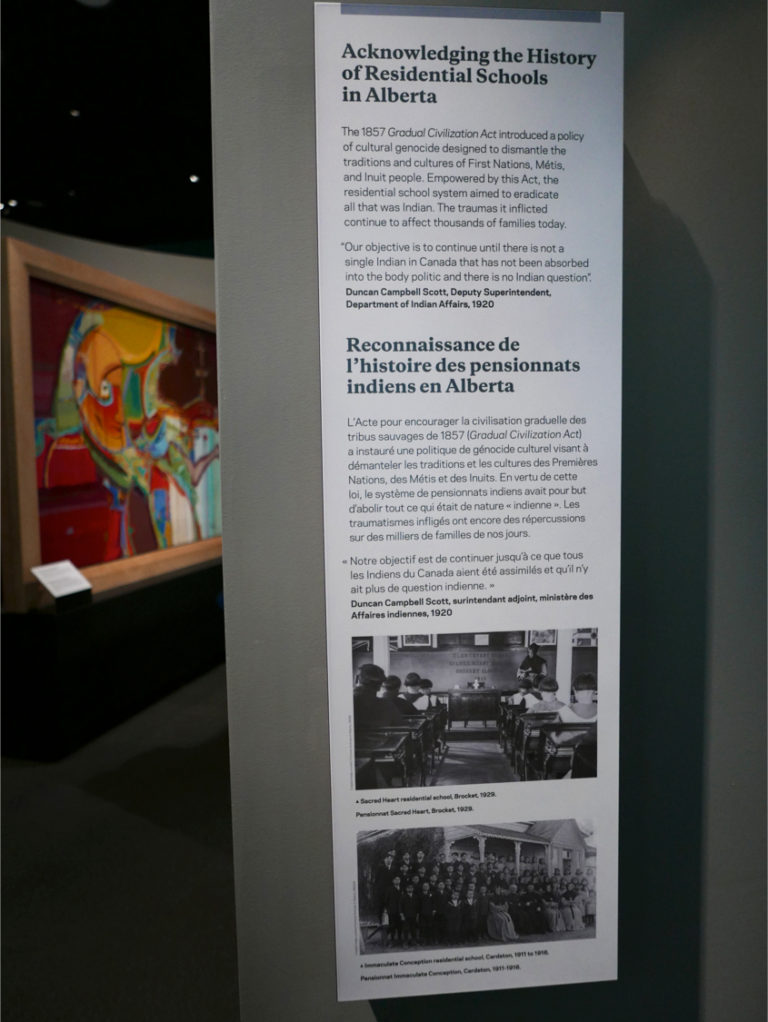

A view of one of the text panels at the residential schools exhibit is titled Acknowledging the History of Residential Schools in Alberta, noting the schools were part of “a policy of cultural genocide designed to dismantle the traditions and cultures of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people.” In the background is a partial view of Alex Janvier's large two-sided canvas Blood Tears (2001), relating to his experiences at Blue Quills Residential School. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A view of one of the text panels at the residential schools exhibit is titled Acknowledging the History of Residential Schools in Alberta, noting the schools were part of “a policy of cultural genocide designed to dismantle the traditions and cultures of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people.” In the background is a partial view of Alex Janvier's large two-sided canvas Blood Tears (2001), relating to his experiences at Blue Quills Residential School. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A small, child-size tipi and a Blackfoot girl’s dress—as well as screens with archival photos of residential school students—are part of the new exhibit on residential schools at the Royal Alberta Museum. Part of the intent was to educate the thousands of youth visitors that the museum gets every year. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A small, child-size tipi and a Blackfoot girl’s dress—as well as screens with archival photos of residential school students—are part of the new exhibit on residential schools at the Royal Alberta Museum. Part of the intent was to educate the thousands of youth visitors that the museum gets every year. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

The residential school exhibit’s layout is roughly circular, with entrances and exits to the east and west. Other objects on display within the circle, besides the Janvier painting, speak to a range of visitor ages and experiences.

Some 60,000 public-school students visit the Royal Alberta Museum each year, so some of the display is designed to connect with and educate them. These elements include a Blackfoot girl’s dress and a replica of a girl’s residential-school uniform, as well as children’s toys like a little moss-bag baby and a child-size tipi. There is also an archival photo print of a young girl holding a dog outside just such a small tipi. A media screen adjacent to the toys and clothes offers visitors the chance to scroll through and enlarge more archival photographs of residential school students.

“There were some junior-high kids gathered around the photos” on opening day, says Harnett. “I said, ‘What do you think?’ And they said, ‘Oh, it’s good.’ Then a girl said ‘This is where my grandma went.’” Other visitors, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, says Harnett, looked at the exhibit’s large map marking residential school sites as well.

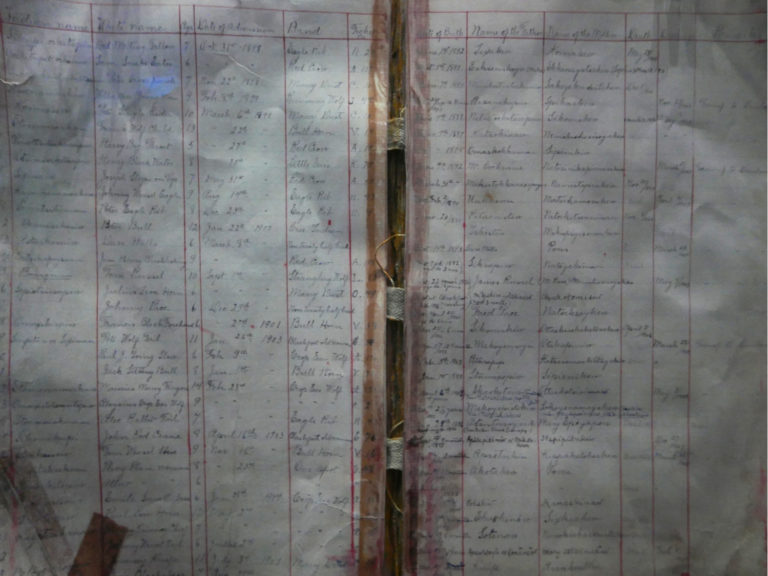

There are also objects in the exhibit that may have heavier meaning for adults—like a small stack of bricks from St. Paul’s Residential School, and a copy of an old ledger that details residential school students’ names, where they were from, when they came to the school—and when they died. “On the page that’s open, some children were noted as ‘discharged,’ but far more children were listed dead or not accounted for,” notes Harnett.

A moss bag baby doll, as well as bricks from St. Paul's Residential School, are part of the new residential schools exhibit at the Royal Alberta Museum. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A moss bag baby doll, as well as bricks from St. Paul's Residential School, are part of the new residential schools exhibit at the Royal Alberta Museum. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A copy of a residential school ledger book is on view at the new exhibit. The book tracked when students were born, where they were from, and when they were discharged—or often, died at school. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

A copy of a residential school ledger book is on view at the new exhibit. The book tracked when students were born, where they were from, and when they were discharged—or often, died at school. Photo: Tanya Harnett.

On the exterior of the circular display, among other media, is a video of First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada advocate Cindy Blackstock. In the video, Blackstock notes that Indigenous children are more likely to be in foster care now than they were during the worst period of residential schools. “This is a current issue,” says Harnett of that video clip. “The momentum has not stopped.” She hopes that visitors leave the exhibit understanding that residential schools are about “the future, the past and our current place in time”—not just a so-called historical moment that is over and done with.

Education about the real effects of residential schools remains sorely needed in the Alberta region and beyond. Just last month, the St. Paul Alternate Education Centre, northeast of Edmonton, was still distributing a Grade 11 social-studies test that asked students to identify the “positive effects” of residential schools. When a screenshot of the test question went viral, it was quickly condemned by Alberta’s Provincial Education Minister, as well as by the Alberta Distance Learning Centre, which originally created the test in 2010. Yet Star Metro Edmonton reported just days later that the founder of a Calgary private school, Neil Webber of Webber Academy, still said, “We want our teachers to discuss both positive and negative aspects of the issue.” And a radio ad broadcast on the Prairies in recent weeks, created by Winnipeg’s Frontier Centre for Public Policy, argued that negative effects of residential schools were a “myth”—an argument that Cardston-raised author Mark DeWolf, whose writings were quoted in the ad, continues to stand by. (The mistake-laden ad was later pulled from online and radio spots following CBC coverage of its inaccurate content.)

“People can say ‘truth and reconciliation,’ but there’s a stronger drive to ‘reconciliation’ than to ‘truth’—the truth has often been left behind,” says Harnett.

Opening day at the new Royal Alberta Museum on October 3, 2018. Thousands of free tickets to the first week of the museum's opening were snapped up quickly. Admission for Indigenous people is always free at the new museum. Photo: Government of Alberta.

Opening day at the new Royal Alberta Museum on October 3, 2018. Thousands of free tickets to the first week of the museum's opening were snapped up quickly. Admission for Indigenous people is always free at the new museum. Photo: Government of Alberta.

Earth sciences and geology is one focus of the Royal Alberta Museum's collection. Here, a new geology display. Photo: Facebook/Royal Alberta Museum.

Earth sciences and geology is one focus of the Royal Alberta Museum's collection. Here, a new geology display. Photo: Facebook/Royal Alberta Museum.

There is also free admission to all Indigenous people at the new museum—part of a big change from the museum’s past approaches to Indigenous people and their experiences. According to the Edmonton Journal’s Paula Simons, a local journalist of settler descent who has attended the museum since she was a child, “The original RAM was built in the late 1960s, a product of its time, and it told a triumphalist story of prairie settlement. The new museum has no First Nations mannequins, no dioramas that treated Indigenous people like exhibits. The museum takes pains to display First Nations and Metis artifacts with respect, with multilingual story boards in many native languages.” (These Indigenous languages used in text panels include Cree, Dene, Blackfoot, Nakota and Michif.)

In tension with this is the fact that the museum still does have a collection of 18,000 objects of Indigenous origin dating from the mid-1800s to present—some of them publicly contested. The collection includes hundreds of Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Dene and Métis cultural objects. And the museum also houses the sacred Manitou Asinîy, or Manitou Rock, which was taken by missionaries in the 1800s and ended up in the RAM collection in 1972. The rock is now part of the museum’s permanent exhibits, currently on display alongside a text describing the story of its theft by the church; this significant and sizeable display was created with careful, long-term input from elders and others on the museum’s Indigenous Content Advisory Panel, with awareness that, in recent years, there have been some calls for the Manitou Asinîy to be returned to its peoples. The resulting display is in a dedicated, pre-admission space to “ensure access to this sacred object,” says a museum release.

In a welcome move, repatriation of First Nations objects is now a bit more visible at the museum than it was before. A page on the RAM website indicates how applications can be filed for repatriation of museum-collection items under the Province of Alberta’s First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act. A related notices page shows that currently, a member of the Kanai Nation is seeking repatriation of “a Black Covered Pipe (accession number H65.247.1a-k), originating from the Blood Tribe, which came into possession of the Royal Alberta Museum in 1965.” Also, a member of the Siksika nation is seeking repatriation of “the (incomplete) Many Hides Beaver Bundle (accession number H67.324.1-32), originating from the Blackfeet Tribe in Montana and used in the Beaver Bundle ceremony, which came into possession of the Royal Alberta Museum in 1967.”

A view of the Ancestral Lands gallery at the Royal Alberta Museum. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

A view of the Ancestral Lands gallery at the Royal Alberta Museum. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

A display at the Human History gallery at the Royal Alberta Museum is titled “Worlds Meet.” Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

A display at the Human History gallery at the Royal Alberta Museum is titled “Worlds Meet.” Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

Certainly, as it’s now the largest museum in Western Canada physically, and stewards a sizeable collection of more than 2.4 million objects, the Royal Alberta Museum will have to think about the model it sets for other museums in the country—both in repatriation and other matters.

Overall, the path to the new museum has not been easy. After 13 years in development, 4 years under construction and $375 million in provincial and federal funding—as well as the threat of a complete cancellation in 2011—the new Royal Alberta Museum officially opened October 3. At 419,000 square feet of total space, including 82,000 square feet of exhibition space, it is twice the size of the former museum. And having been relocated downtown to the arts district, it is now just steps from the Art Gallery of Alberta and not far from MacEwan University’s new downtown arts campus.

Thousands of free tickets for opening week are already completely booked—in fact, 21,500 available online in September were snapped up in just six hours. “We are absolutely excited by the enthusiasm that is being shown,” museum executive director Christopher Robinson told the CBC. “We have been dark for a while”—the old museum shuttered in 2015 for the move—“and there’s a lot of expectation.” (Regular one-day admission for adults is $19 for adults, $14 for seniors and $10 for youth 7 to 17 years of age—a yearlong “Mammoth Pass” is only about double that for each price segment.)

The new museum building is on a previously occupied by a Canada Post office and distribution centre. The building It was designed by Canadian firm DIALOG, with New York’s Ralph Appelbaum Associates designing the Human History and Natural History galleries and New York’s Lee H. Skolnick Architecture designing the Children’s Gallery and the Bug Gallery. An Indigenous Content Advisory Panel helped develop exhibits for the new museum, too.

“There are windows into the back-of-house,” lead DIALOG architect Donna Clare has explained, noting transparency as an aspect of the new design. “You get glimpses of the curators at work…maybe see them moving a mammoth back and forth to the gallery.”

The architects tried to incorporate elements from the old postal building into the museum as well: Ernestine Tahedl mosaic murals, commissioned by the federal government in 1966 for the post office, are part of the facade of the new museum, while the post-office clock hangs on museum’s south-west side, in approximately the same location it previously occupied.

An exterior view of the new Royal Alberta Museum. The Canadian firm DIALOG was in charge of the building architecture, which integrated some elements from the old site's postal office—the clock at left was on that old building, and was re-installed in roughly the same place. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

An exterior view of the new Royal Alberta Museum. The Canadian firm DIALOG was in charge of the building architecture, which integrated some elements from the old site's postal office—the clock at left was on that old building, and was re-installed in roughly the same place. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

Another element of the old postal office that was integrated into the new Royal Alberta Museum were Ernestine Tahdel murals from the 1960s. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

Another element of the old postal office that was integrated into the new Royal Alberta Museum were Ernestine Tahdel murals from the 1960s. Photo: Courtesy Royal Alberta Museum.

Yet amid the opening celebrations—much of it well earned—there are some concerns and gaps yet to be addressed, both at the RAM in particular and in the wider museum scene in general.

For one, even though it is LEED certified, the new RAM has already been blamed for a jump in the provincial government’s own greenhouse gas emissions. “Museums have higher energy consumptions than other government buildings because many exhibits, artifacts and storage require 24/7 controls to ensure appropriate temperature, humidity and air quality levels,” the Infrastructure Ministry told the Edmonton Journal on this point in July. An annual report quoted by the paper added, “It is not possible to predict the energy use and greenhouse gas emissions of a new facility with a high level of accuracy before the facility completes one full year of operations.”

And there is still much left to be done in terms of museums and First Peoples. In coming years, Tanya Harnett says she hopes to see not just more and better residential school exhibits in existing Canadian museums, but also experience the founding and curating of an entirely new art gallery and museum dedicated to and run by First Peoples.

“Years ago, Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.—the Indian Group of 7—were calling for an independent museum, and SCANA, the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry, said we need our own place,” Harnett notes. “People are funnelling into [existing] institutions, and now the question is, Are we moving away from the notion of having our independent space? That is a discussion that will continue.”

In coming weeks and years, the new residential schools exhibit in Edmonton will continue to change as needed, and adapt to the needs of Canada’s First Peoples. Harnett hopes that the way the exhibit is designed makes it a safe space—somewhere people feel free to enter, exit and interact with as desired.

“Someone had put a tobacco honouring down” beside the Alex Janvier painting on opening day, observes Harnett. It’s prompting a new element: “We were thinking, how can we make sure this is a place where this [type of offering] is respected?” Harnett reflects. “We decided to include a smudge bowl. We want to make sure that everyone understands: this is a living culture.”

This article was corrected and clarified on October 10 and 11, 2018, to reflect the following: The location of the residential schools exhibit is in the Human History Hall, and Chris Robinson is executive director (not CEO) of the museum. Also, the lead image display shows cultural objects originating with many First Nations, and in the residential schools exhibit, the school uniform is a replica while the Blackfoot girl’s dress is original. Some additional detail was also added regarding the Manitou Asinîy display development.

Drums and cultural objects originating with several First Nations are on view at the Royal Alberta Museum. A page on the museum's website indicates how groups and individuals can apply to repatriate objects from the collection. A separate permanent exhibit also addresses the cultural genocide involving residential schools. Photo: Royal Alberta Museum.

Drums and cultural objects originating with several First Nations are on view at the Royal Alberta Museum. A page on the museum's website indicates how groups and individuals can apply to repatriate objects from the collection. A separate permanent exhibit also addresses the cultural genocide involving residential schools. Photo: Royal Alberta Museum.