In mid-September, I was attempting to escape the large crowds of Hamilton’s Supercrawl, the city’s annual arts and music festival, and the lit-up entrance of Hamilton Artists Inc. felt like a promising option. As soon as I walked in, I noticed a large pile of sand in the centre of the room and watched as a young artist fell onto it—disrupting its stillness with her small frame and leaving behind imprints as a record of her movement. I had unknowingly walked in on a performance, which I later learned was I see in the sea the sea by Jana Omar Elkhatib, a Palestinian Canadian performance artist and writer based in Waterloo.

Elkhatib held a book tightly in her hands. A microphone hung above the sand pile, catching Elkhatib’s voice in waves through a loop pedal. Her voice echoed and looped over itself, isolating words from their sentences to create an almost incoherent murmur. She lifted herself up, slipping and falling as she found her footing. She took one step and then another, faster and faster, but went nowhere as her feet dug deeper into the sand. Her voice filled the room with raw, uninhibited recitations, which eventually turned into a mumble as she walked out of the room, ending the performance.

For a few moments the audience was silent. Elkhatib’s performance had moved me in ways my vocabulary couldn’t describe. I fixated on the book left behind—Mahmoud Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness, which reflects on the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon in prose. I felt her pain as if it were my own long before knowing we shared a Palestinian homeland. I was fascinated by Elkhatib’s ability to go beyond words and form an intimate connection through performance. It was a coincidence that I met Elkhatib right as she started her residency at Hamilton Artists Inc. (also known as The Inc.), but it took a conscious commitment to spend the next seven weeks with her—learning more about performance art, her work and her aspirations—all while trying to find the right words to describe her process and her practice.

During the first of our weekly encounters, Elkhatib showed me her makeshift desk in the main gallery before leading me down to The Inc.’s basement—a place to which she often escaped, for solitude. “The residency is allowing me to really embed myself, as opposed to just showing up and finding an audience and performing. Spending time [in the gallery] is allowing me to create an intimate relationship with the space…when the audience shows up, I am inviting them into a space that I know…and that’s very powerful,” Elkhatib explains.

Elkhatib completed her undergraduate thesis year in fine arts at the University of Waterloo, with a focus in performance art, this past spring. Aside from her studies, she had performed solo just once before, at La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse in Montreal. The pace of her life shifted when artist and independent curator Abedar Kamgari, The Inc.’s programming director, invited her to be included in the recent exhibition “To see and see again,” and then to be The Inc.’s performer in residence, after finding a video of one of Elkhatib’s undergraduate thesis performances online. Elkhatib has since performed two solo shows there: Another retelling to the young on September 7 and I see in the sea the sea on September 14. And she spent her residency researching, writing and developing a third performance, titled A body is a distant witness, which she performed on October 26.

Elkhatib began immersing herself in performance art two years ago, somewhat by coincidence. After learning that she was missing a credit, Elkhatib found the only course that fit her schedule was a new performance art class—the first of its kind at the University of Waterloo. Bojana Videkanic, a performance artist and art historian, was teaching it. “Immediately it was like, ‘Oh, this is a language I understand,’ and it was a pleasant surprise…the spontaneity of it really drew me,” Elkhatib explains.

From the first day of the class, Elkhatib formed a connection with Videkanic, whose own artistic practice often focuses on her experiences of displacement from the former Yugoslavia. Elkhatib grew up between Canada and the United Arab Emirates, and her work has often explored separation and longing in relation to her family’s Palestinian roots and identity, personal and collective memory, and the inheritance of complex histories eroded by colonization.

“What’s interesting is that performance really honours audience as witness in the same way that writing’s relationship to the reader does…. I remember [Videkanic] always repeating, ‘There’s no such thing as a performance without audience,’” Elkhatib says. “There’s sincerity and honesty in considering how a reader is actually a completion of a work, in the same way that an audience is.”

In her performances, Elkhatib often uses sound technology as an extension of the body to represent personal and collective memories. In Another retelling to the young, she uses a tape deck to play recorded conversations with her four-year-old niece about her great-grandfather. She manipulates and overwrites the sound during the live performance, conveying the difficult passage of stories and memories across generations. The tape deck doubles as a radio and has significant meaning—her great-grandfather communicated with his family primarily through public radio announcements while separated behind new borders for the last 17 years of his life. For Elkhatib’s mother, her grandfather was but a voice on the radio throughout her upbringing in Gaza.

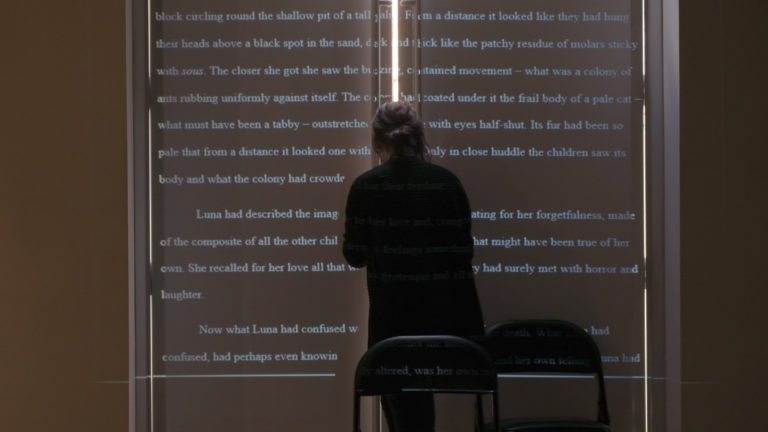

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

During a residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in early October, Elkhatib recalls that one of her peers, Aizita Magaña, observed that her performances of deeply personal writing are an alchemy of bodies past and present. Elkhatib began to think more about active witnessing and the trust that’s established when you allow the audience to carry your stories with them. “I often thought, maybe if I did too much performance the writing will disappear or if I did too much writing, I will disappear—just because of the nature of my writing work, especially being rooted in the memories of others…. [After] Banff, it was more pronounced for me why I was doing the kind of performance work I was, why I was drawn to this intermingling of my experiences with those of others,” Elkhatib says.

When it comes to Palestinian identity and how it influences her work, Elkhatib reflects on the difficultly of simply identifying what makes her experiences Palestinian. “Personally, I’ve been feeling estranged from place, even people…it’s interesting how [we] delineate whether our longing and grief come from a particularly Palestinian experience or if it’s the intimate experience that then tells us something about the collective losses. I lost my dad when I was really young, so what does it mean to look at Palestine and look at loss of life [and] my father and think about both of these things as very present absences?”

Since losing her father at 11 years old, Elkhatib has become a record-keeper in her family, collecting and writing narratives for a book project about his life. As that project nears completion, she has felt the weight of the slow accumulation of voices and memories of others. Performance became a space where she could reflect.

“When I came to performance, it was like a different medium that stepped outside of words and language and writing and became about what I was doing…for the first time I was reflecting back on myself,” Elkhatib explains. “All this work about what it means to hold the memory inside a body, what it means to hold the absence of someone in the living, it all comes back really to this project.”

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

Jana Omar Elkhatib, performance documentation, 2019.

When I returned to The Inc. for A body is a distant witness, Elkhatib’s final performance for her residency, I found that it had changed; it was no longer about a story of two lovers, as she had originally planned. Thinking through discourses of intimacy in response to separation, she had instead developed a text about distances—literal and metaphorical—altering spans of time and geography. Notably, the performance was now also about her father.

“It’s very, very, very slow work and then suddenly an idea comes as if fully formed…. [Although] it’s not magical, it was the work of weeks of responding to and fitting into the form and parameters I had established for the performance. But essentially all those ruminations are the work and experience of years,” Elkhatib explains. It felt fitting that she would bring her two passions together in a performance. Her own writing ended up as the sound piece, allowing her to explore poetry and write in ways that were new to her.

Developing a performance about her father for the first time allowed her to share fragments of a private narrative without being entirely confessional, and to Elkhatib, there is a real dignity to that. Now more than ever she feels the gravity of finishing her father’s story and, in the coming year, she’s going to be travelling, researching and writing the book.

“It’s actually almost like coming back to a starting point,” Elkhatib says. “This is really where all my interest in memory is coming from.”

Jana Omar Elkhatib, I see in the sea the sea, September 14, 2019, at Hamilton Artists Inc. Photo Grant Alan Holt

Jana Omar Elkhatib, I see in the sea the sea, September 14, 2019, at Hamilton Artists Inc. Photo Grant Alan Holt