Emily Fitzpatrick: Okay, we are speaking over Zoom, during a pandemic, on unreliable WiFi. Six months have passed and we are still trying to settle into a new normal founded on uncertainty. I really cannot believe that the potential of the digital still remains underexplored and underappreciated. Have you noticed a shift in this once-urgent call-for-action, or are we still struggling with the concept of online exhibitions?

Letticia Cosbert Miller: In preparation for this conversation, I tried to do some research on the current state of affairs, nationally and globally, as far as the art world is concerned. It’s always been difficult to find examples and information about presenting art online, and I thought, “Oh, this time it’ll be different! I’ll just type in ‘COVID’ and ‘online exhibition’ and I’ll be overwhelmed with results.” Nope. Most of the results were about the galleries, theatres, etc. all over the world rushing to reopen, and, of course, their critics.

EF: That doesn’t surprise me. I feel like the response to anything problematic happening within the art world is all about damage control. At the beginning of COVID, I remember a general community panic in finding solutions and good examples for virtual programming. Now it seems like we aren’t asking those difficult questions anymore. Many institutions have abandoned the whole discussion about online programming, which I think you and I predicted would happen.

LCM: Totally. But also, “real life” is not around the corner. Everyone seems to be working on the assumption that we’ll all be able to reopen and stay open—I’m still very skeptical. The situation changes so frequently and in unexpected ways.

EF: We’ve been conditioned to overvalue the materiality of art, which has influenced the importance of a physical experience. While we have been viewing physical artwork on screens for a long time (through documentation, blogs and social media) the notion of treating online curation and digital exhibition-making as respected practices is so under-documented. What online programming have you seen lately that’s exciting?

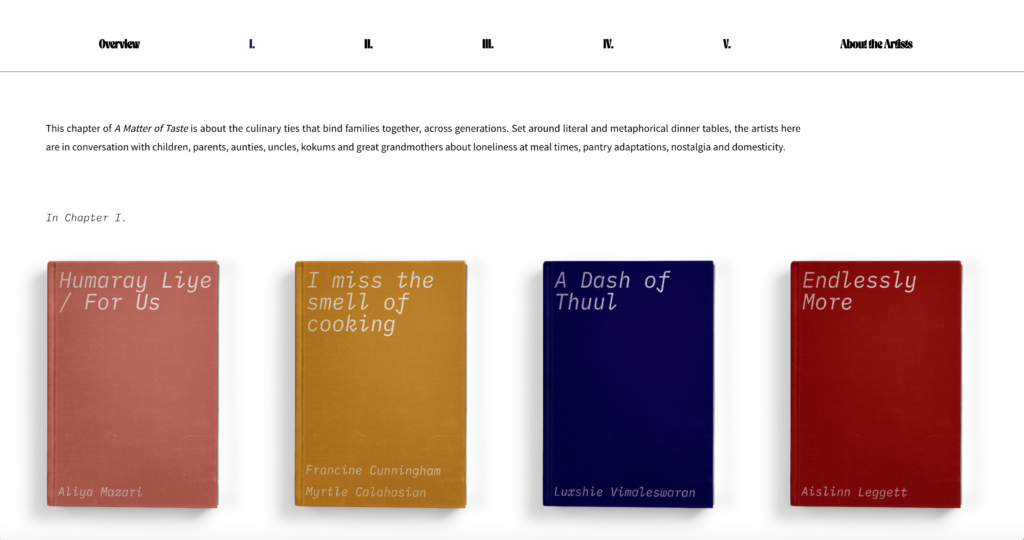

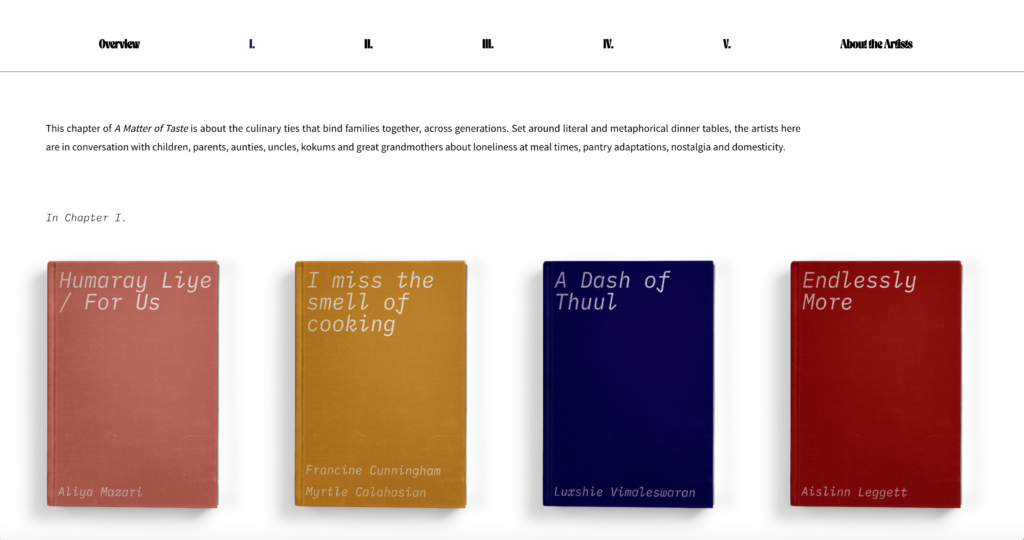

LCM: Well, AKA, an artist-run centre in Saskatoon, in June launched “tofeelclose,” an online exhibition space with new artist commissions added biweekly. The works by Carrie Allison, Erika DeFreitas and Shellie Zhang are among my favourites. I’ve been working on a new online exhibition titled “A Matter of Taste,” which features new work (all made specifically for digital) by 21 artists and writers. It’s about food and the cultures that surround it, and it launched in August. I found it fascinating, the way everyone around me seemed to be renegotiating their relationships to food as the pandemic began to affect their lives. So we made an open call for submissions, and the result is a collection of writing and artwork exploring consumption, appropriation, scarcity, waste and access.

Chapter 1 view for “A Matter of Taste,” via Koffler.Digital.

Chapter 5 view for “A Matter of Taste,” via Koffler.Digital.

LCM: In addition to digital exhibitions, you curate a physical space—how are you feeling about all of this and the possibility of reopening?

EF: At Trinity Square Video, we’re working with the Digital Justice Lab on a transmedia publication called Virtual Grounds. It will focus on feminist perspectives in digital survival and sustainability, and it will hopefully act as a toolkit for the public. Some of the research involves urban surveillance algorithms, collective understandings of consent, slow internet manifestos, and virtual DIY Black art spaces. It’s launching October 14: I am so excited! In terms of the physical space, actually, I am concerned about losing focus on experimenting with online programming, but the pressure to reopen is obvious and consuming.

LCM: This might be pessimistic, but why do people really go to galleries, and why are they willing to risk their lives and the lives of others during a global pandemic to do so? And I don’t mean viewing, engaging with, or experiencing art, because there are lots of ways to do that that do not involve a gallery, like online, for example!

I should be careful not to idealize the internet too much. It’s far from utopic, but it’s different, this sense of freedom and intimacy when experiencing art online.

EF: Even that term “engage”—is physical engagement more valuable than online engagement? That is the general consensus, and a huge idea to unpack.

LCM: It’s true. But those of us who connect online want to meet people; we want to translate our online relationships into IRL relationships. It doesn’t need to be one or the other; it needs to be fluid, and it needs to encompass both modes of community building.

EF: Certain works obviously lend themselves better to a gallery setting. But I think the rush to go to galleries right now is not necessary, and it’s indicative of an audience that hasn’t taken much time or interest to engage in other options, and so is now at a loss.

LCM: And of an audience that has bought into the idea that IRL is the best and only way to experience art. And, maybe, of an audience for whom even acknowledging anything else would destroy the myth, compromise a fragile hierarchy and compromise the many positions that exist to safeguard and replicate this system.

EF: We’ve talked before about the hierarchies in art presentation: gallery exhibitions are at the top, and education, public programming and digital initiatives are secondary. I can’t help but compare this conversation to ones about equity in arts. This is why things remain stagnant and people complacent. And it’s because of this hierarchy too, I suppose. Not to go on a tangent or anything…

LCM: I hope this isn’t a tangent because it’s all I want to talk about!

EF: The online presentation of film festivals has been making me think about hierarchy too, and the ways online viewing has removed so much social pressure. If I want to engage, then I engage on my own time, and if I miss it, I miss it.

LCM: Yes, I feel the same! Film festivals should be available to more than a select few who can afford to purchase tickets (maybe even plane tickets), take time off work and stand in lines for hours. A simple feature like closed captioning, which is rare in theatres, is now easily activated from the comfort of your living room. Why isn’t it that every film in theatres has closed captioning?

EF: I often hear the argument that subtitling gets in the way or changes the aesthetic. I’m not sure why it’s not standardized yet. Well, I know why: it’s a decision to change the format to make a work accessible. It acknowledges a different way of viewing.

LCM: If someone thinks putting work online or putting subtitles on a video or turning the volume up or having a transcript compromises the experience, then we don’t need to work together. Surprisingly, these are rebuttals I hear mostly from administrators and curators—rarely from artists. I’m very fortunate in that I commission new work almost exclusively from artists, specifically for the digital space, so these are conversations that we’re having at the outset, not after the fact, and even that isn’t enough. I could and need to do more.

EF: Those rebuttals only cater to the vision of a single person, instead of a broader audience. Can we talk about the ways surveillance in gallery spaces is also a barrier to access and a limit on experience?

LCM: Yes, I think that’s also why I love and value the digital space; it’s one based on trust—trust that you’ll engage with the work in the way you think is best. No one is hovering over you, following you, reminding you that you are a threat to the safety of the material before you, which is an experience I’m so familiar with. Too familiar. [laughs].

EF: I would love to see the analytics on forms of surveillance in physical and virtual galleries. I’d be interested to gauge audiences online about how they are feeling when engaging with work when they know they aren’t being physically watched. What are people’s experiences like in comparison?

LCM: I would love to see that data too. I should be careful not to idealize the internet too much. It’s far from utopic, but it’s different, this sense of freedom and intimacy when experiencing art online. I’m reminded of the Dana Schutz painting in the Whitney Biennial a couple of years ago. I read all about it and I saw the protest photos. I thought I knew everything I could know about the work, and then it was so much worse in person than I could have even imagined.

You said it: the internet isn’t utopic. It does mirror the systems of oppression that are obvious IRL—through algorithms, AI bias, facial recognition—but the malleability of technology provides opportunities and hacks for protection, platforms for global community congregation, and foundations to consider our digital rights responsively.

EF: What did you notice in real life?

LCM: Well, for one, I didn’t realize that it was sculptural. The actual deforming of Emmett Till’s face almost looked like papier maché; it was raised and came off of the canvas, which I think is even more disgusting in terms of her artistic vision or concept. But I also think, seeing it in that gallery with other people seeing me see, it was almost more painful than just digesting the news about it online.

EF: You felt watched?

LCM: Yeah, it was obvious. There was all this controversy around it. And here’s a Black girl, me, looking at this work that has all of this emotion and critique around it. I felt watched, and even if I wasn’t being watched, I was very aware of the fact that somebody might stumble upon me looking at it—the anticipation of being watched. It was really uncomfortable, the idea that being caught seeing this work was, I don’t know, maybe an endorsement of it? I’ll be honest, that’s the way I feel viewing a lot of work that has to do with Black pain or certain aspects of Black identity. It’s hard to view it in mixed company.

EF: I guess viewing art at home is a kind of security mechanism, or a form of protection. At least it provides a little more agency in your sense of personal safety under surveillance culture. You said it: the internet isn’t utopic. It does mirror the systems of oppression that are obvious IRL—through algorithms, AI bias, facial recognition—but the malleability of technology also provides opportunities and hacks for protection, platforms for global community congregation, and foundations to consider our digital rights responsively. Accountability seems to live online more tangibly than in physical spaces.

LCM: Yes, I agree with that entirely. I hope we begin to understand that going online or presenting your work online doesn’t compromise the experience. We need to do away with the idea that the work loses its meaning if you’re not personally, physically with it.

EF: That view is completely elitist and ableist as well.

LCM: And racist. If this is your view, it reveals, to me, that you don’t actually care about the conversation that the artist is trying to have with you. You don’t care about the research, or the context. You only care about being in a room with a thing, and the social capital that you gain by having proximity to art and its value.

EF: Yes. And then people will use a platform like Instagram to publicize that experience, but can’t see Instagram ever being a presentation platform itself. (Jordan Firstman’s IG impressions, for example, are true artworks.) They might use the platform for social capital, but it’s still so “lowbrow” that they can’t accept art actually existing there first.

The entire apparatus of the art world is not built to support digital work…. One of the only silver linings of this moment is the appetite to imagine a new world, and in a lot of ways, artists and thinkers have been trying to do that work in the digital realm for a long time.

LCM: You know, I don’t tolerate Instagram slander [laughs] but I also never placed much value in gallery spaces. I’m happy and privileged to have access to them, but for me, and maybe it’s a generational thing, I grew up on the internet. If it wasn’t for Tumblr, Twitter, Myspace and Instagram, I don’t know what I would know about art. I didn’t have parents who could take me to a local gallery on the weekend. They didn’t have that kind of leisure time, and because of that, these kinds of cultural experiences weren’t in their vocabulary.

EF: Yeah, same. Me coming from a small farming town, my family wasn’t taking me to the gallery. I didn’t go to a gallery until my first or second year in university. It was for an assignment.

LCM: I think about these kinds of experiences all the time. Who gets access to knowledge?

EF: And more, who feels welcomed in gallery spaces and who gets to be part of the scene? This moment is interesting though: everyone seems to have their eyes on digital and its possibilities.

LCM: It’s been very difficult to make a case for digital programming that is independent, and not secondary or ancillary to physical programming.

EF: Well, for example, the Canada Council’s Digital Strategy Fund grants don’t support artistic production or artist fees—or staffing costs.

LCM: And it’s in the name! The entire apparatus of the art world isn’t built to support digital work. Half of my job, it seems, is trying to convince people that the digital space is a viable, fruitful space for artistic production, research and engagement with the public. One of the only silver linings of this moment is the appetite to imagine a new world, and in a lot of ways, artists and thinkers have been trying to do that work in the digital realm for a long time. Loretta Todd (the incredible Cree/Métis filmmaker and scholar) comes to mind as someone who saw the rise of the internet age as an opportunity to build new communities on a decolonized, virtual landscape. A fresh start. I really hope Facebook hasn’t totally fucked it up [laughs].

What’s your dream for the digital future?

EF: I want us to stop restaging the same practices and same ways of seeing art online. I’m not interested in seeing a 3D rendering of a physical exhibition created on SketchUp, or naming a bunch of images as a solution for online exhibitions–even though I’ve totally done it! This is a chance to learn how online exhibitions can work differently from physical exhibitions and should be considered their own medium. The internet is already the best spot to come together and make new communities, so how can we congregate around art that uses the structure of the internet and the apparatuses of online technologies?

This is why the GIF is perfect and an amazing medium to build upon. The curatorial essay for “Well Now WTF?,” by Wade Wallerstein, points that out plainly; the format of the GIF was built for your DMs. It’s a simple format with the capacity to communicate complex, global stories that everyone can understand and relate to. It’s its own thing…nothing can copy it IRL. It is a digital creation that utilizes the systems of the digital to exist.

LCM: I mean, the fact is that a lot of smaller galleries and artist-run centres can’t maintain the investment of human and financial resources they require to build online spaces that aren’t just documentations of physical shows. Even if their intentions are good.

EF: It’s way too much work for most organizations. A lot of things that were started in the past few months will be abandoned, for the obvious reason that most folks do not have the capacity, or interest, to maintain them. Existing roles and positions in galleries do not have the bandwidth to truly engage with digital structures and languages, which could be achievable with different opportunities.

LCM: My dream for the digital future is that we’ll see the government funding bodies, federal, provincial and municipal, prioritize digital initiatives differently. I want accessible, digital initiatives to become requirements for funding, and to be considered from the very beginning of a project or exhibition’s formulation. And I want to have access to the curator’s ideas, I want to hear from the artists, I want it all to be shared. I want that to be required of all institutions. All of them.

EF: I’d also like some options for meeting online that don’t involve a VR headset and which aren’t Zoom. I currently have Zoom fatigue [laughs]. But still, how can we get together online?

LCM: I only have Zoom fatigue from things that I feel like I need to be doing, that I don’t truly want to do. Also, COVID capitalism and the revolution have exhausted all of my energy. Maybe the future includes freedom from artist talks? [laughs]

EF: Also, right now provides an opportunity to think about how digital can improve and present other models for organizational structures. Protocols in how we document and how we archive programming and collections are founded on traditional systems. The Care Package project, for example, which is co-programmed by Mada Masr and Sarah Rifky and supported by the Mohammad and Mahera Abu Ghazaleh (MMAG) Foundation, is a series of collected content from contributors who create a theme or direction around notions of solidarity and communal care. The format is simple, and it’s the perfect use of a blog format. For me it offers an alternative to web archival creation with a variety of content surrounding a theme.

Few people have taken advantage of using technologies to reimagine how practiced, institutional activities can be revised. Web archives like the Wayback Machine and even social media pages are so interesting when considering alternative models for archive creation. They’re great advocacy tools because they continue to witness crime and abuse, but are at the same time tied up with surveillance capitalism.

LCM: It’s also important to make clear that digital work presented online automatically creates an archive. As someone who doesn’t have an arts degree, and who grew up on the internet and the unprecedented access it provided me, I don’t know what I would do if I couldn’t learn through online databases and resources. Even simple things like interviews inspire and teach me so much.

Putting work online creates a living archive. It’s not just documentation. It allows you to engage with the work at various points and return to it with new perspectives. I struggle with the assumed finality of an exhibition—what if the mounting of the exhibition was only the beginning of the research?

EF: Exactly. To capitalize on the nature of the internet and its longevity can encourage a way of producing work that you know you can change. The artist and curator can be thinking about future interpretations, opportunities to build and ways of being responsive. And I’m not suggesting that this would create erasure of narratives, but there can be a record of reaction and accountability—an open-endedness to counter the authoritative exhibition space.

LCM: Yes, responsiveness is what the art world is lacking, and the willingness to truly be accountable to its audiences.

Browser view of “Well Now WTF?,” an online exhibition curated by Faith Holland, Lorna Mills and Wade Wallerstein. wellnow.wtf

Browser view of “Well Now WTF?,” an online exhibition curated by Faith Holland, Lorna Mills and Wade Wallerstein. wellnow.wtf