Inspired by mythology, Vicky Sabourin creates otherworldly stories and tableaux vivants out of handmade objects, felted animals, natural materials and durational performances. In “Colts raisin,” exhibited at Montreal’s galerie atelier b this fall, Sabourin’s material practice was invested with the deeply personal too. On the exhibition’s closing day, Sabourin spoke about rituals surrounding loss and working from the sentimental depth of objects.

Eva Crocker: Can you tell me more about the inspiration for “Colts raisin”?

Vicky Sabourin: My uncle passed away in January 2019, and in May I emptied his home. My uncle and grandmother lived together in that house for 40 years. Growing up, I spent a lot of time there. Suddenly it felt like this piece of my youth was disappearing.

What do you do with all the things that belonged to someone who passed away? Do you get rid of everything? If not, what do you keep? What has sentimental value?

There were things I discarded, recycled or donated, but there were objects that spoke to me for various reasons, and I put them aside. Over two or three months, as I progressed through this archeological dig through the house, it occurred to me that maybe it was more than a personal collection I was gathering—it could be a project.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Materials include found used women‘s shoe insoles and an old pack of Colts grape cigars; the cigars were stolen during the exhibition. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Materials include found used women‘s shoe insoles and an old pack of Colts grape cigars; the cigars were stolen during the exhibition. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

EC: You often work with found objects and recreate objects you have encountered in the real world. How has your relationship to found objects evolved in this work?

VS: In the past, I tried to rebuild spaces. Now, I had the entirety of the house available to me. I was deciding what to keep and how to interact with objects that were not replicas. At first I wondered where my voice was as an artist if I wasn’t remaking objects or searching for stand-ins. I realized my voice came through in the selection of objects.

Some objects I picked because I thought they were aesthetically interesting. I always loved my uncle, but there was a distance between us, which was one of the effects of his trauma rippling through our family. Going through all of his belongings after he died felt voyeuristic, to have access to everything with no censor. But through that, I was able to see similarities in our personalities. I could see a kinship between us beyond the wall of his trauma, and it was a bit healing for me.

Other objects were like strange clues, things I didn’t understand and I will never have answers to: Who is the person in this small photograph? Why did he keep this poster? Why all these used women’s shoe insoles?

I brought my studio table into the gallery, along with objects that have been sitting on it for many years, and some of my ceramics. They mixed with the artifacts I unearthed from my uncle’s home and it felt like an encounter between us, a way to understand our relationship.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation view), 2019. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation view), 2019. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

EC: You mentioned that your uncle’s life was shaped by the fact that he spent a large portion of his childhood in a juvenile detention institute. He was one of tens of thousands called the Duplessis Orphans, after former Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis—victims of a large-scale scheme that institutionalized children in asylums to collect federal subsidies set aside for hospitals. How are the personal and political intertwined in this work?

VS: The Duplessis Orphans’ story, this historical tragedy, was always a part of my family. It wasn’t taboo, but we only talked about it a bit. Over the years, I learned about what happened to my uncle and to many other children.

It explained a lot about my family dynamics, the trauma my uncle carried, and some of my grandmother’s behaviours. His trauma had a ripple effect, I think, that also went beyond my family.

I’m interested in trauma and questions of ethics. We’ve heard a lot of stories from the orphans themselves, where they describe the miserable things they endured. That was not where I wanted to go with this project. For me, this was about the aftermath of that trauma.

EC: Could you describe some of your uncle’s objects, and the objects you created?

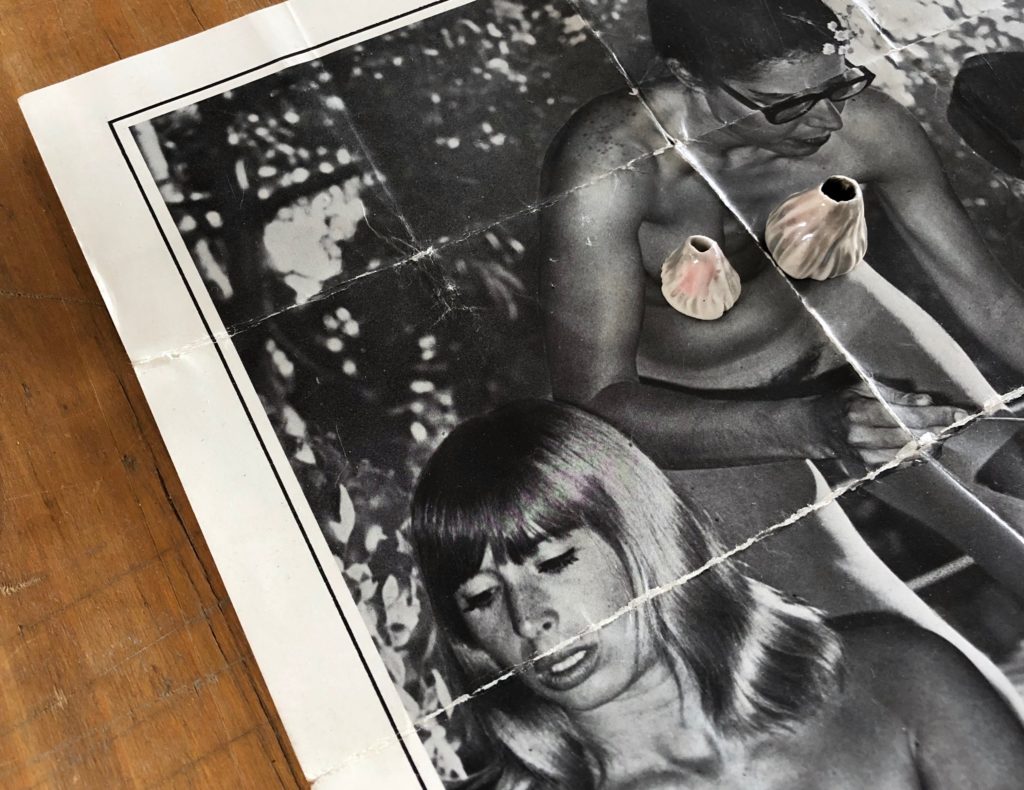

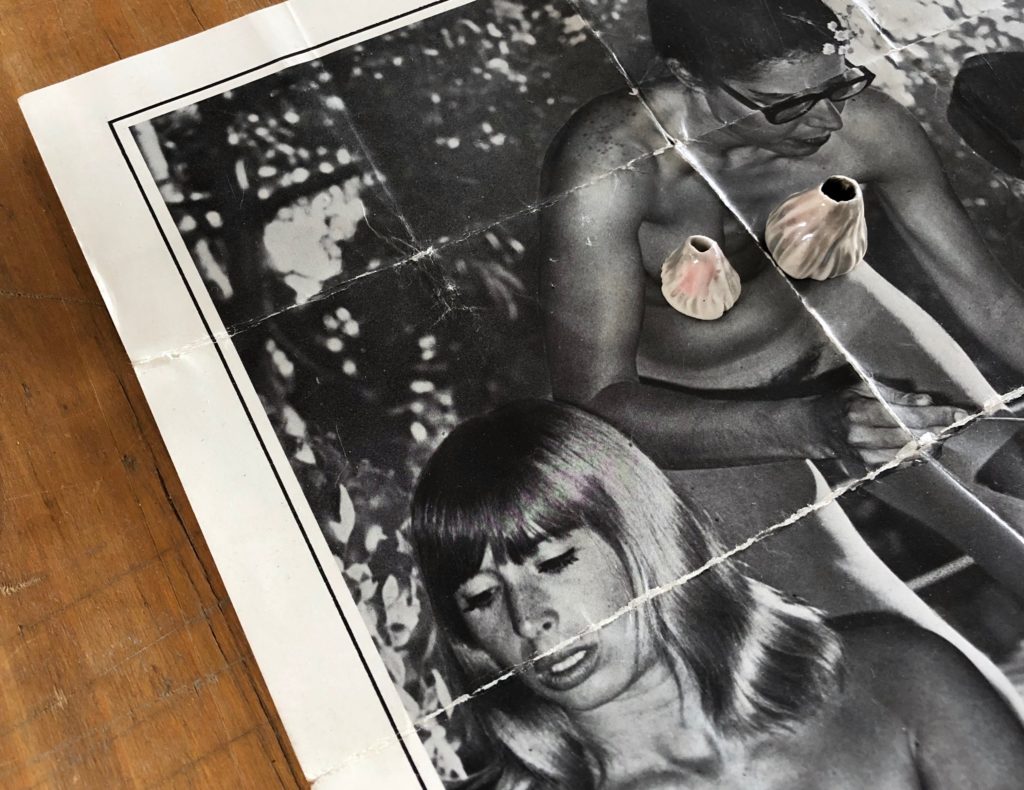

VS: There’s a poster that looks torn out of a National Geographic—a black-and-white photograph of nude people having breakfast, maybe at a nudist camp. To me that was really intriguing—as far as I know, my uncle never had a partner and was kind of this mysterious, lonely man. It gave some access to his intimate personal life that we, as his family, were definitely not a part of. I placed two handmade ceramic barnacles on the breasts of one of the women in the photograph. It reminds me of Madonna’s Jean Paul Gaultier cone bra—a bit of humour but also quite gentle as a gesture.

I really like the grouping of my uncle’s IDs because you can see him age. But it was important to me to protect his identity because of the dark history he was part of. I placed ceramic barnacles on his IDs—his face was always covered by a barnacle, as though it grew on him.

There was a badge with the name of [Institut Doréa], where he was forcibly kept, one of the Duplessis institutions. Why would someone keep a memento of a very dark and traumatic past? Placed on the table with the other objects it became a signifier and an anchor point to talk about this history.

I also sculpted two ceramic ghost pipes, a strange and beautiful plant that can be used to make a tincture to treat PTSD.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Found poster and porcelain barnacles. Courtesy the artist.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

It’s very strange to have pieces stolen from an exhibition about loss.

…somehow this brings me back to a place that’s more familiar… trying to find the objects again, working from memory.

EC: Sadly, some of your uncle’s possessions were stolen from the exhibition. Has that changed the direction of the project?

VS: I was with my mother and sister visiting the show when I realized objects had been stolen. It’s very strange to have pieces stolen from an exhibition about loss.

I often see my work in different chapters, and somehow this brings me back to a place that’s more familiar. Not the theft, but trying to find the objects again, working from memory.

The pocket watch that was stolen, for example—I don’t even know its make or brand. So retracing the stolen objects could become another chapter.

EC: Is there anything else you would like people to know about the work?

VS: “Colts raisin” was kind of a prologue. I’ve kept all the furniture from my uncle’s bedroom with the idea of recreating it in a future installation. I want to work more with scent—I was working with scent when my uncle passed away. I had carved maggots out of ceramics to create an installation with a hand-felted dead goat. The maggots were soaked in an oil to smell like lilies, a beautiful scent to some people but one that reminds me of death and funerals. That project came to a halt and those maggots ended up on my studio table in “Colts raisin.”

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. The newspaper was stolen during the exhibition. Photo: Marie-Claude Brault. Courtesy the artist.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. The newspaper was stolen during the exhibition. Photo: Marie-Claude Brault. Courtesy the artist.

My uncle and grandmother’s house had this very strong, pungent smell that was quite unpleasant. For the past 10 years, all of my siblings, my mother and I have avoided staying in the house too long because the smell would cling to your clothes and hair. When I was emptying and cleaning, the smell was always present, but I became accustomed to it. Now that I know the detestable smell is dissipating, I want to recreate it—I’m longing for it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Photo IDs and ceramic barnacles. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.

Vicky Sabourin‘s “Colts raisin” (installation detail), 2019. Photo IDs and ceramic barnacles. Photo: Clara Lacasse. Courtesy the artist.