Beading is meditative; it is ceremony. Threads interwoven through generations recreate the same bodily acts stitch after stitch after stitch. Carrie Allison’s previous work was predominately based on the gestural acts of drawing, and it was the gestural and meditative qualities of beading that drew her to this new medium. Allison’s recent exhibition, “These Threads Hold Memory,” uses beading as a methodology to decolonize Western and hierarchical ways of knowing and disseminating knowledge. “These Threads Hold Memory” asserts that beading is a valid form of technology and knowledge transfer, even if it does not conform to the definitions or standards set by the dominant settler-colonial perspectives found in Canadian society.

It was during the Calgary Stampede when Carrie Allison and I sat down for coffee to talk about her exhibition “These Threads Hold Memory” at the New Gallery in Calgary, and about the prayerful act of beading. Outside the café, we were surrounded by fake cowboys in their regalia—plaid shirts, cowboy hats and boots—and Stampede décor: hay bales, fake horses and acrylic paintings, some with appropriated Indigenous imagery. It seemed like a fitting, if not ironic, background to a chat about her work. We talked about time spent beading, how the laborious movements ground you and allow you to be present. For Allison, the pull of the thread is like pulling your ancestors to you to spend time with you, to reflect on all that has led to this point. This was Allison’s first exhibition on the land that is now known as Alberta, land that her familial ancestors used to call home.

Missy LeBlanc: Where did the title for the exhibition, “These Threads Hold Memories,” come from?

Carrie Allison: I started thinking about beading in general. I knew that all of the pieces in the exhibition were going to be beadwork or have beadwork in them. For the last two years I have been working specifically or predominantly with beadwork or beads. I was thinking about thread and I was also thinking about ways of holding and containing memory. In Kiskisohcikew (2018), for instance, I used beading as a mnemonic device, and I feel as if that sort of performance is encapsulated in this beadwork. So the title came through a lot of conversations and reflections on beading in general.

ML: The exhibition is about decentering and Indigenizing colonial modes of knowing and knowledge dissemination. What was the reasoning behind using beadwork as the methodology to decolonize Western ways of knowledge transfer and pedagogy?

CA: I think it really comes down to labour and time—that is a very Indigenous and predominantly femme-identifying thing to do. Our work—or the way I see our work—is time-consuming, labour-intensive and largely devalued by Western society and Western art practices.

I love the meditative and grounding practice of beading. I also read a lot about beading practices before I even started beading and before I even felt comfortable with it. I read a lot of Sherry Farrell Racette and Carmen Robertson. I looked at a lot of other beaders. Ruth Cuthand is probably the first beader I fell in love with and her Trading Series (2009); Amy Malbeuf is another. There are so many artists I looked at before I started to try beading. I did a lot of research before I started, to see what was appropriate for me to bead. I stayed away from certain designs from other [people’s work] because it was really important for me to do my own take on beading. I was really interested in using the gesture of beading, but also speaking to the things I know—or the things I wanted to know.

150 (2017) was really about shared histories, but also becoming familiar with those histories, or at least attempting to in a very time-consuming way. I fell in love with Amy Malbeuf. In an interview she did for Canadian Art, Malbeuf talks about how beading is an act of resistance historically. I loved the quiet resistance Malbeuf spoke of, the quiet rebellion with this simple, powerful gesture. For a large part of colonized Canada, I think it was for almost a century, making regalia was banned. I think that was another aspect I fell in love with. Using beading, using lingo of the West like numbers or QR codes, is a way for me to mix and match and reflect my ancestry.

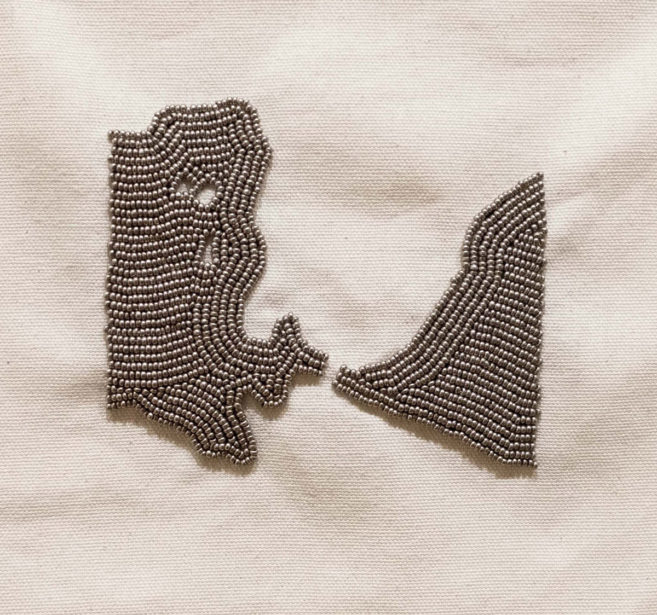

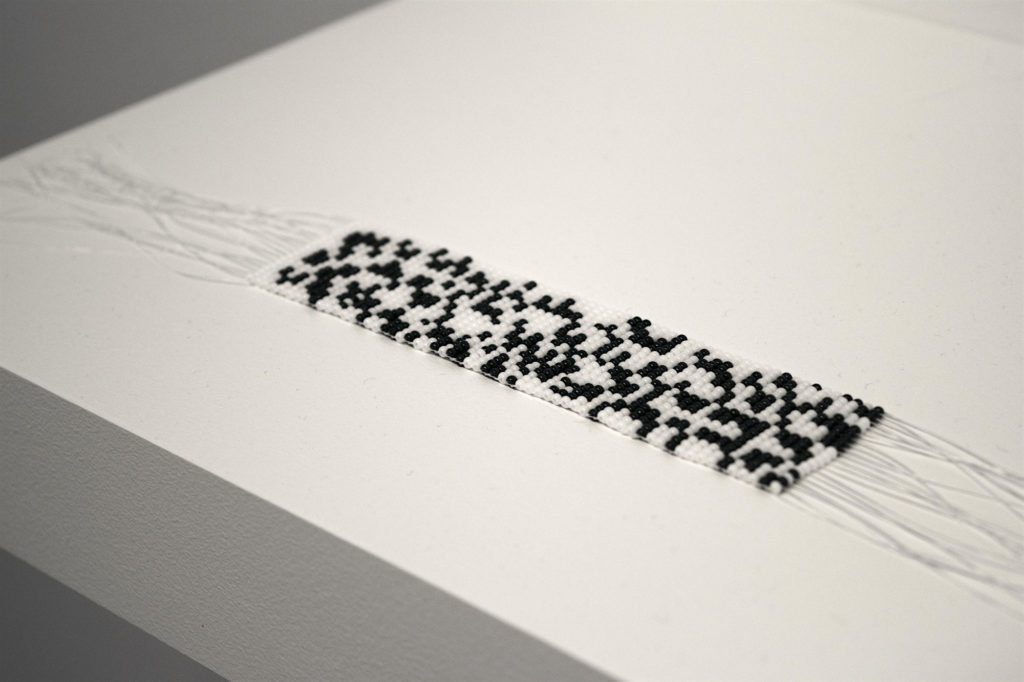

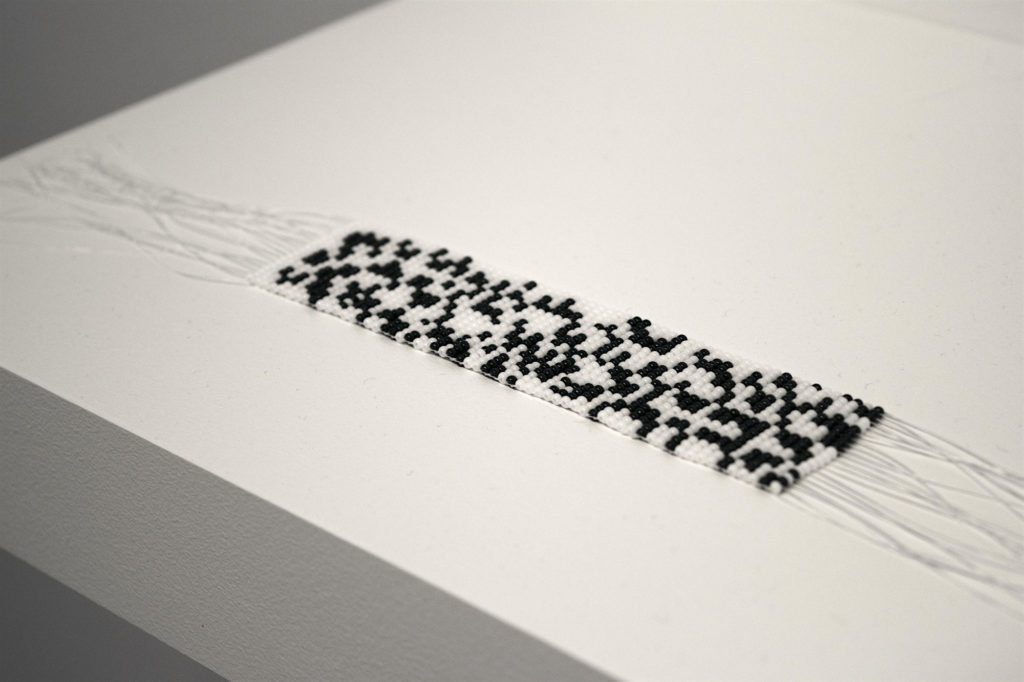

Carrie Allison, An Identity Metaphor (installation view), 2017. Beads on pine with reflective surface. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, An Identity Metaphor (installation view), 2017. Beads on pine with reflective surface. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

ML: A previous article for Canadian Art noted that a major part of your practice is using beadwork to connect to your matrilineal ancestors. Can you expand on that?

CA: Beading is one way to connect. My immediate family doesn’t bead, from what I know, but I found cousins who do bead. Most of my family are crazy good sewists. Everyone in my family sews, and that is another way I connect; I think it comes down to a gesture. Beading and sewing also take time: time spent with, thinking or visiting with ancestors. My grandmother is no longer here but I feel I can connect through this time spent on this one thing.

The article you read was about pillows I made. I have them at home and I love them so much. Specifically, sitting down and thinking about the women in my life who have had so much impact on me as a person. Making those pillows was like honouring them through this gesture. A lot of my practice is about honouring through making. Whether it’s the Heart River piece I made for my series Sîpîy (River) (2018), or the pillows or plants that I am working, beading is a way of reconnecting not only with matrilineal roots but also with physical objects and devoting time to thought.

ML: Like a shared gestural movement that you can trace back through the generations.

CA: That sort of connection: threads literally going through women in my life who have done similar gestures.

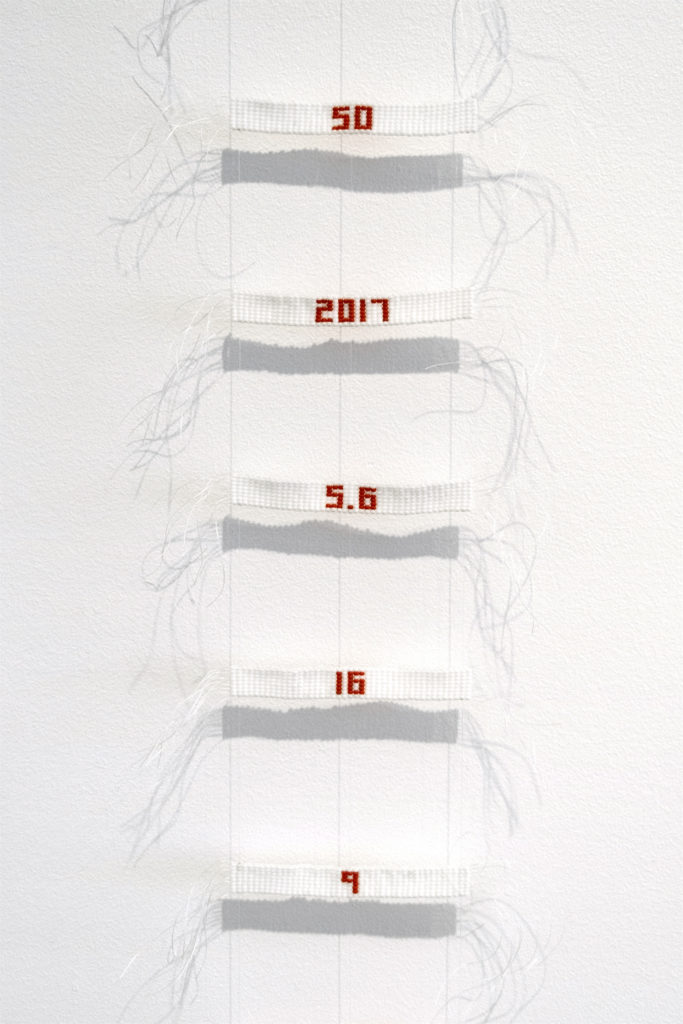

Carrie Allison, 150 (detail installation view), 2017. Glass beads, fishing line and pine. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, 150 (installation view), 2017. Glass beads, fishing line and pine. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

ML: Your piece 150 is a series of loom-beaded objects with dates or numbers that have significant importance or connection to Indigenous history. What was your process in deciding on the number? What do you feel is the most significant number that folks should be aware of?

CA: So, my process was really doing a lot of research, reading and extracting numbers. The reason I chose numbers was because Western society loves statistics and 150 is making it easy for them. Getting all those numbers wasn’t really difficult. I had specific rules: [numbers were sourced from] the time between Confederation and 2017, and I knew I had to have 150 numbers, which would act as stand-ins for the events or issues shared by many Indigenous peoples. This creates a nation-to-nation dialogue as people are informed about the past and current issues facing Indigenous people. All my sources are on the 150 website.

I think what sparked 150 was The Inconvenient Indian (2013) by Thomas King, which has a lot of statistics in it. So many people were reading it and talking about how informative it was. But then there are so many more things King didn’t mention in the Canadian context because he focused on Turtle Island as a whole. I wanted to focus on Canada and all the terrible things Canada has done.

In terms of the most important number, I don’t know. I think that 1996 is a huge one because I don’t think most people understand that residential schools existed in our lifetime. I know my partner was really surprised when I told him there were residential schools in Canada as recently as 1996. Some non-Indigenous people think of it as in the past and that Indigenous peoples should “get over it.” People our age lived through it. Residential school was a huge mode of assimilation, a violent colonial tactic in trying to control us. That’s just one example of many. That’s the one I think of because not only did it end in my lifetime, 10 years after I was born, but the legacies still live on. My family is still struggling through the legacies of residential schools because my grandmother went to residential school and we still feel that. It’s a lot of work to work through all that trauma and to contextualize it within. Is it just the way I am or is it something more traumatic we hold within ourselves, that has been passed down socially or within our blood?

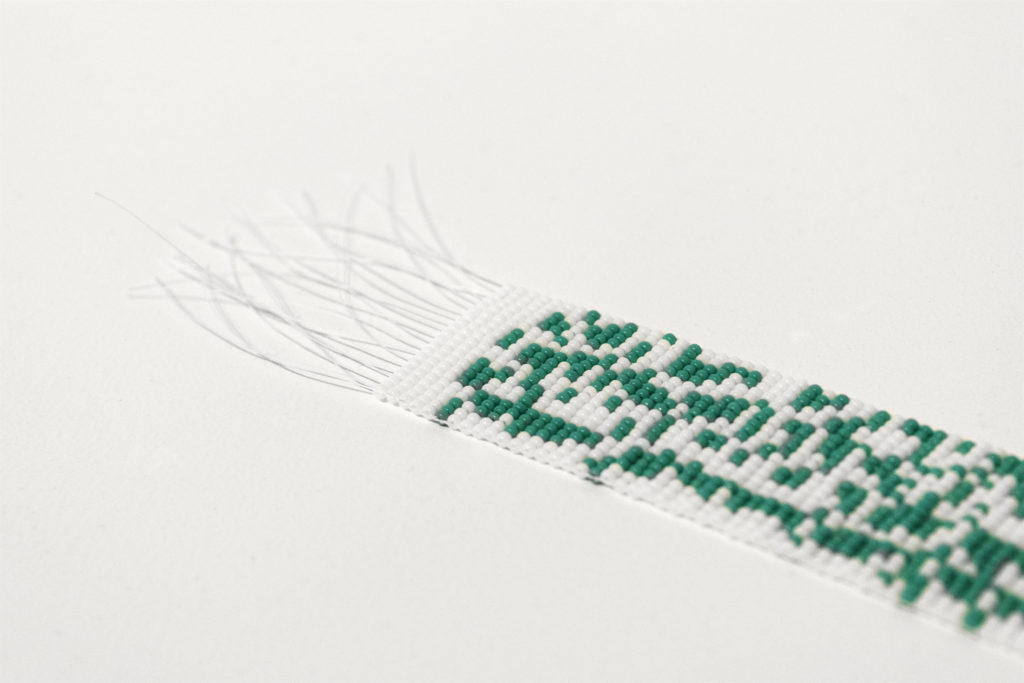

ML: In the exhibition, “These Threads Hold Memory,” your work Kiskisohcikew (2018) consists of an audio track of someone speaking Cree and three loom-beaded objects—one black and white, one teal and white and one yellow and white. As this work was previously a performance piece, are these beaded objects ephemera from previous performances of Kiskisohcikew?

CA: I really want to learn my language and my aunty Ivy, my great-aunty rather (she is my grandmother’s sister), speaks Cree fluently. So we just had conversations over the phone and I recorded them, obviously with her permission, and we were talking about language and family. I would get her to translate certain words to learn.

The audio track in “These Threads Hold Memory” is the same audio from the original performances. To create the audio, I took the whole recording and cut out the Cree words; then I made a track of my aunty just saying the Cree words. I would then repeat the words in the performance. It was a memory piece. I knew what Cree words she was saying because I had conversations with her about them, so I would reflect on it myself. It wasn’t about teaching people how to speak Cree; it was for me. I was using beading as a way to learn better—[to learn] while I’m doing something, and using beading as a mnemonic device, as repetition.

ML: To hold space for that practice of learning.

CA: Yeah, and to share it with people. I didn’t want to share learning Cree with people, the audience; I wanted them to know the labour that goes into learning and reclaiming something, how tedious it is, and the fact that I shouldn’t have to do this. Learning my language shouldn’t be something I have to find money for. I shouldn’t have to do the labour of trying to learn my own language; that shouldn’t be something anyone should have to do. I should just know my mother tongue. My grandmother shouldn’t have had to endure what she did. My great grandmother only spoke Cree; the only thing she knew in English was, “God damn dye.” I’m pretty sure it’s because she loved bingo—that’s my theory. But my grandmother went to residential school pretty young. She didn’t speak Cree, or she was very averse to it. She didn’t speak Cree and would always answer things in English and I think that has to do with residential schools. We should all know our mother tongues and have a connection to them. It’s so much about being with community and knowing and reading the landscape. I’m assuming if I knew Cree it would have to do with the landscape, those stories of Northwestern Alberta. It’s a lot of pressure, and unless I take the time to learn it, my children won’t be able to learn it, and that’s really fucked up—that’s not okay.

“It wasn’t about teaching people how to speak Cree; it was for me. I was using beading…as a mnemonic device, as repetition. I didn’t want to share learning Cree with people, the audience; I wanted them to know the labour that goes into learning and reclaiming something, how tedious it is, and the fact that I shouldn’t have to do this.”

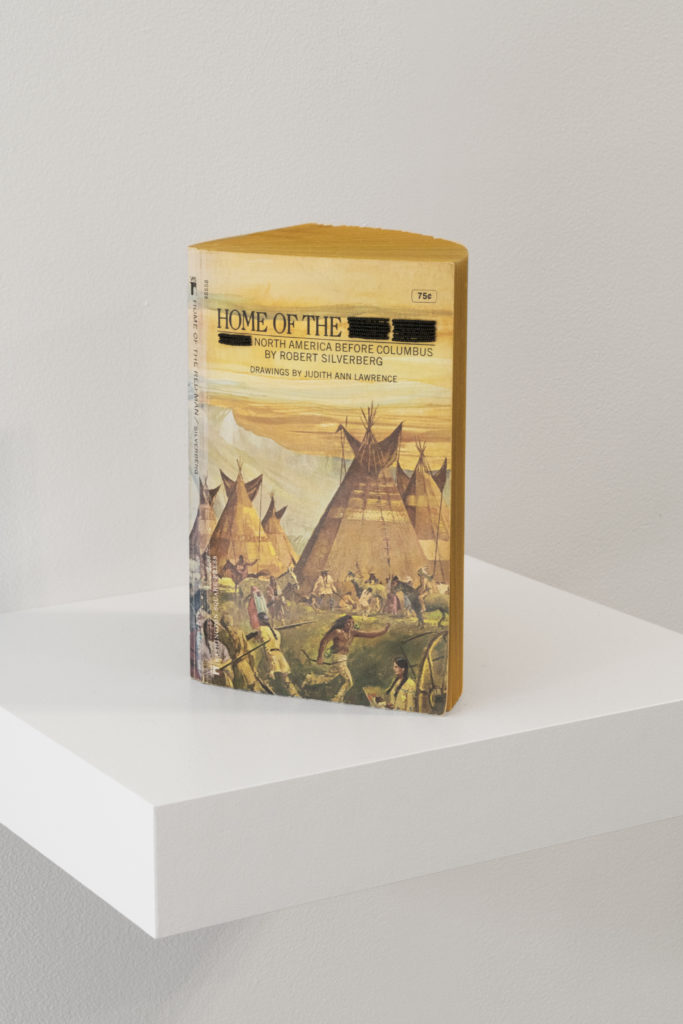

Carrie Allison, Book Intervention: Library of misrepresentation and False Narratives (detail). Research material and beaded books. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, Book Intervention: Library of misrepresentation and False Narratives (detail). Research material and beaded books. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

ML: The patterns of the beaded components of in “These Threads Hold Memory” don’t appear as though they are based on traditional beadwork patterns; they are abstracted. Can you tell me a bit more about the patterns used to create the beaded components?

CA: My intention was that any time my aunty or I were speaking, I would pick up a coloured bead. When there was silence in the recording and performance, the beadwork was supposed to be white. My beadwork changed when I put it into motion because it’s hard to remember and do everything and reflect on what I am saying. It’s more of an intention than an actual thing put into my beading practice. Occasionally I would do the original pattern but I think it’s more aesthetic than anything else at this point.

ML: For me, I find that the act of beading, from sitting down and coming up with a design and colours to the actual act, can be meditative and calming. I was wondering if you get this feeling as well?

CA: Yeah, beading can be challenging and it can be sad too. I’ve been trying to look at sadness and hard topics. There is validity in time spent with something, whether it’s hard or joyful, and hard things hold place in our lives. Beadwork for me is about building connections and working through them.

With my art practice there are similarities with what I did before beadwork, but there is a lot of slowness, mindfulness and intention that goes into beading, which I didn’t have with my previous practice. I still value the work I did before. But with beadwork I’m building toward something, even though I don’t know what that something is. If it’s to pass along to future generations or to share space with other people or to just give time to something outside of myself.

When I made the Heart River piece it was incredibly impactful for me because I was thinking about water and land, the way that water and land have been affected by resource extraction, and my family’s connection to Heart River. When you spend like 300 hours on something, you are probably going to think about a lot of different things. Beading was very calming for me. It is a prayerful act, most of the time. On the Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA) website is a video of a lecture by Sherry Farrell Racette—“The Radical Stitch: Bead Until Your Fingers Bleed”—in which she talks about beading as a prayerful act (unless you have a deadline, and then you’re stabbing yourself). I listened to that a lot when I was doing my master’s degree, and making and getting ready to write my thesis.

There are so many people I’m building on who have had a tremendous impact, who have built so much into beading as a contemporary art form, or into beadwork in general. So many people have done so much work in order for me to feel how I feel about beadwork. So I’m very thankful for their work.

Carrie Allison, Kiskisohcikew (detail), 2018. Beaded components from performance. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, Kiskisohcikew (installation view), 2018. Beaded components from performance. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, Kiskisohcikew (detail), 2018. Beaded components from performance. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.

Carrie Allison, Kiskisohcikew (detail), 2018. Beaded components from performance. Courtesy the artist and The New Gallery.