MARINA ROY: The last time we met at your studio, you mentioned having just come back from LA, where you went to the Getty. You said something to the effect that the old paintings you were looking at still felt incredibly immediate in terms of what they conveyed and offered you as a painter. I’m interested in the agency of artworks as well. Can you elaborate on that experience and its relevance for you?

SEAN ALWARD: Walking into the Getty, I made a beeline for the Renaissance and Baroque rooms, and the first painting I saw was a small crucifixion by El Greco. Wow! The intense feeling conveyed by the black abstract clouds and blazing peripheral light was strong, but what really hit me was knowing that El Greco felt the same mysterious dark energy while he painted the scene as I did while standing there. It transmitted the energy of intense consciousness—its shapes, its materials, did this. These odd little patches of paint collapsed time and space (in this case the more than four hundred years since El Greco worked in Spain) and still it conveyed a powerful present experience of vitality. This is the language of painting and it is wonderful. What were you thinking of in relation to the agency of artworks?

MR: When I say agency I mean something a little more than art’s autonomy. There’s a kind of animistic quality to some artworks, how they can be arresting, how they can be deeply moving and meaningful to certain viewers but based on something that’s hard to put one’s finger on. I tend to agree that “good” art allows us to have these types of experiences (or epiphanies). Painting is a confluence of mineral pigments and spirits, linseed or other vegetal oils, artistic and personal experience, and energy, or some other intuitive connection in the handling of all these materials. There is something about the time and place it was made, and all this is greater than the sum of its parts. That energy, or whatever one wants to call it, gathers in the art object, and comes to exist as a separate entity, detached from its origins. It’s a powerful thing that bridges vast temporalities, and can suddenly feel immediate. I keep going back to this passage by Hans Belting: “Our bodies function as media themselves, living media…[that] rely on two symbolic acts which both involve our living body: the act of fabrication and the act of perception, the one being the purpose of the other.” This relates to your bodily reaction to the El Greco painting I think. But it also relates to our responsibility as artists, in how we engage with the material world. While political content still often trumps any consideration of the materiality of the work, we encounter a greater attention placed on materials in artmaking today, how they point directly to a political economy.

All these materials have loaded histories and their own peculiar properties. I often think of artmaking in Frankenstein-like terms: artists animate materials to convey a sense of vitality.

SA: True, the way we engage as artists can be pretty varied. I am not inclined to make art out of social politics as a starting point, but I am interested in how we engage with the material world and come to understand it and ourselves. For me, social politics in art extends from this. This approach became clearer when, a little more than 10 years ago, I encountered a group of fake construction workers. One Saturday morning I saw a bunch of middle-aged guys in City of Vancouver construction vests digging away in a ditch where the road was torn up. However, something seemed odd because it was the weekend and crews didn’t operate then. It became clear that they were impersonating City workers and were actually picking through the remains of Vancouver’s first municipal dump searching for artifacts, mostly bottles. At one point a guy pulled out an ornate perfume bottle from the dirt, popped the cork and passed it around for all to smell. That bottle had been in the ground for well over a century. In talking with them, I understood that these rogue archaeologists had an alternate map of the city in their minds, an invisible map of what lay under the surface of the city and how things looked each decade after colonial settlement, and much earlier.

I don’t want to make too literal a connection here, but your work also strikes me as being deeply “grounded” in its material choices. I’m thinking specifically about the mural you did for Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, Your Kingdom to Command (2016), using a mix of bitumen, pigment, paint, shellac…what got you going in that direction? Did you start with those weird mixtures or was it the politics of our current environmental mess that led you there?

Marina Roy, Your Kingdom to Command, 2016. Mural with latex paint, bitumen, red-iron oxide, shellac and tar on plywood, with tree stumps and fountain. 2.56 x 6.09 metres overall. Courtesy the artist/Vancouver Art Gallery.

Marina Roy, Your Kingdom to Command, 2016. Mural with latex paint, bitumen, red-iron oxide, shellac and tar on plywood, with tree stumps and fountain. 2.56 x 6.09 metres overall. Courtesy the artist/Vancouver Art Gallery.

MR: It’s hard to reconstruct how one gets to a place with a project. I guess it’s a combination of past experience and present urgency. Bitumen/asphaltum is a material I’ve been working with since my BFA days, when I was etching: one adds an asphaltum layer to a copper or zinc plate in order to protect it from being eaten away by the acid. I always enjoyed the quality and tonal range of browns afforded by asphaltum. Later I learned that it was used by painters in the late Middle Ages. Over time, it was discovered that asphaltum paint had qualities that were not advantageous—being quite solvent, it seeped into adjacent colours. So painters gave up on this material quite early, it seems. It was just too animate perhaps! It isn’t a mineral but live matter—bitumen is made of ancient microscopic life forms such as diatoms, so the idea of extinction is embedded in the very material itself.

I’ve followed the extraction processes of oil from Northern Alberta over the past decade, and looked at a lot of damaged landscapes. I wanted to make silhouettes of life forms that evoked that kind of toxicity (tailing ponds). In Your Kingdom to Command, I dropped bitumen paint into water-based latex paint to create alchemical, Fibonacci-like patterns, and experimented with pools of paint that would breach their boundaries, to evoke mining spills. It took a lot of experimenting with asphaltum—grinding it, mixing it with various oils and solvents—to figure out how to make it work. This material, along with paint made from red-iron oxide, appealed to me: the cultural connotations of bitumen point to global consumption and the petroleum industry (which will ultimately result in climate change and accelerated extinction), and the use of red-iron oxide refers to Paleolithic art and materials used in cave painting (another passion).

Truth be told, your midden paintings were a huge inspiration for me, although for you archaeology and First Nations/settler history were the subtext. Could you elaborate a little more on that trajectory, from the moment you met those rogue archaeologists to your research and art practice after that? I can’t remember whether you had started integrating coal dust into those paintings yet, or whether it was after, but that was an incredible moment in terms of how your practice unfolded.

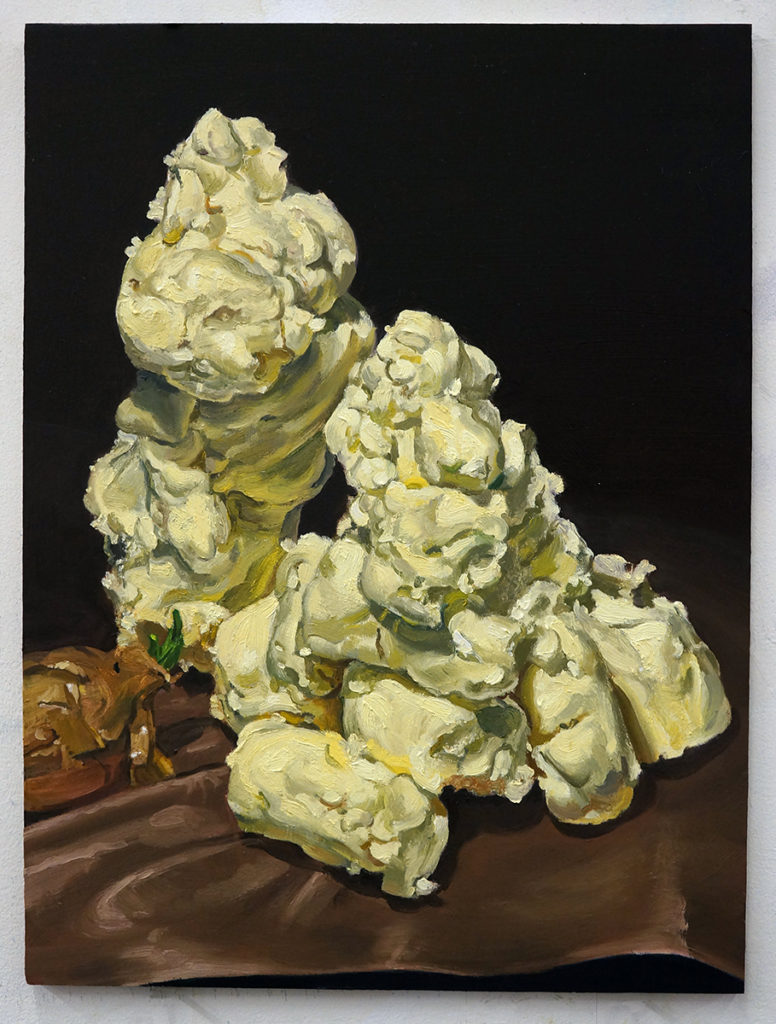

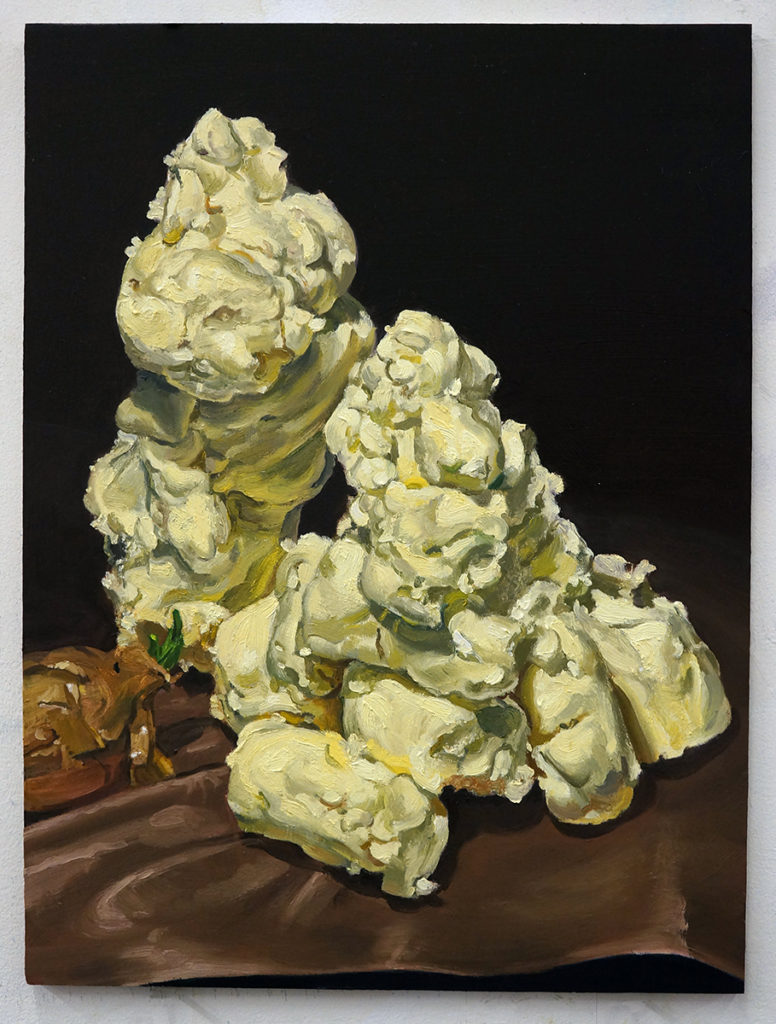

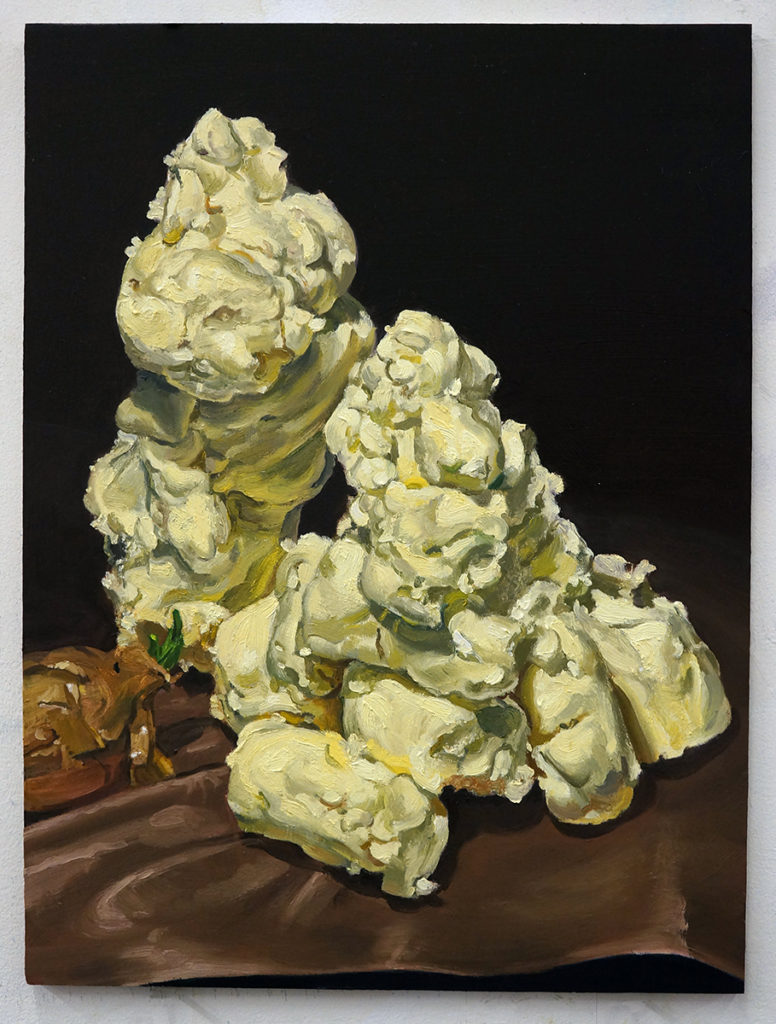

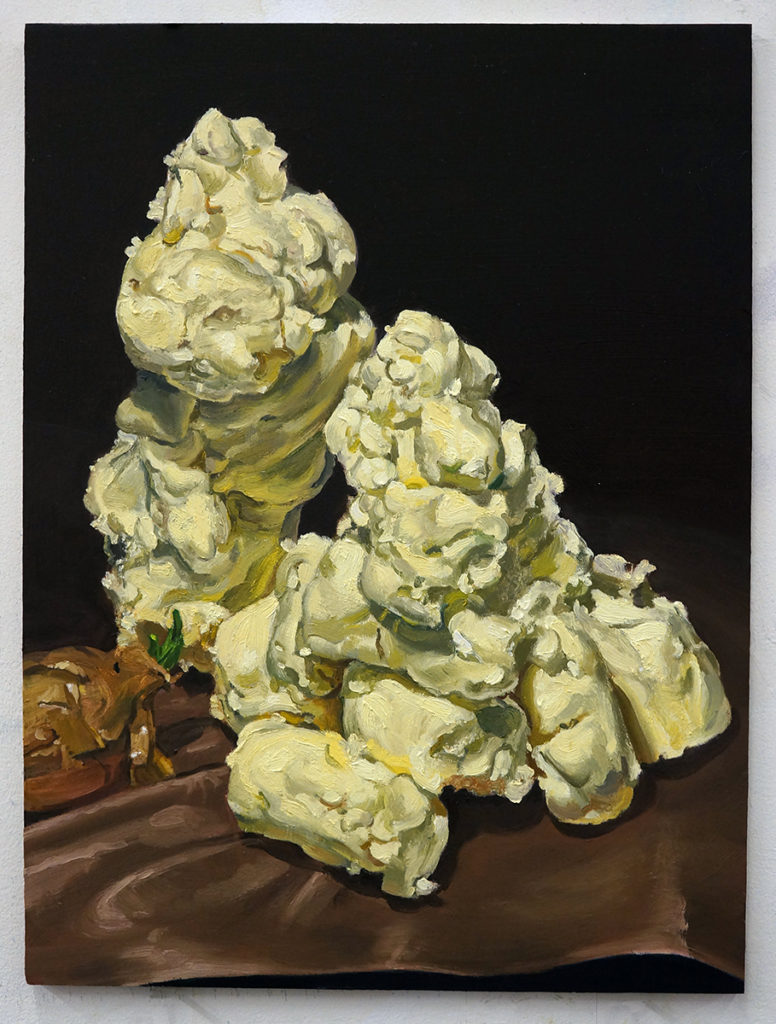

Sean Alward, Butter, 2019. Oil on panel, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Sean Alward, Dolmen, 2019. Oil on linen, 12x16 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Sean Alward, Butter Block, 2019. Oil on linen, 9 x 12 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Sean Alward, Oompapa (Heinrich S.), 2019. Oil on panel, 12 x 16 inches.

SA: I spent quite a bit of time hanging out with one of the rogue archaeologists/ bottle diggers at various locations around town. He was a colourful character who reminded me a bit of Gabby Hayes (an actor who played grizzled old-timers in Westerns in the 1930s and ’40s). At the same time, I was getting to know some legitimate archaeologists who absolutely hated the rogue diggers (whose activities are illegal). One side are self-educated blue-collar workers and the other side are professional academics. I was fascinated by their shared interest in history and contrasting approaches.

Basically everything in our environment, living and non-living, contains its own history and alludes to the conditions that shaped it. Art, artifacts, plants, animals, geological landscapes can all be viewed this way. A lot of this information can be gleaned by careful observation and inquiry. Shortly after my archaeological experiences I started making my own paints from pigments gathered on exploratory trips around Vancouver, including coal but also clay, minerals, pollen, algae. All these materials have loaded histories and their own peculiar properties. I often think of artmaking in Frankenstein-like terms: artists animate materials to convey a sense of vitality, both viscerally and conceptually. What are your thoughts on animism and art? Maybe this is very literal, but is this also connected to your animated films?

MR: Animation has the potential to engage new anti-narrative forms that imitate, albeit nonsensically, the transformative process of life itself. The becoming of life parallels the strange assemblages created through artistic play, which can occur quite unexpectedly and randomly—becoming the subject of animation itself. While visiting Europe a few years back, I took a lot of photographs of the grotesque ornamentation found on Baroque architecture, as well as anomalous specimens in natural history and medical museums. My favourite was the Musée Fragonard, in Paris, a museum of anatomical oddities. I used a lot of this visual research to create a contemporary grotesque in my animated works. And I spend a lot of time sifting through images to create a personal archive of things that resonate with me. I repurpose them as “actors” in my own imaginary theatre—a composite/assemblage of monstrous grotesque forms: part mineral, plant, animal, human and micro-organism. Systems of biological exchange become phantasmic, excessive, unproductive—resisting the instrumental logic of colonizing impulses at the service of human exceptionalism.

Your newest paintings have something of the aura of the Baroque, and one feels almost fooled into thinking they’re from that era. The objects have an animate, almost surreal quality, as if you’ve created still-life actants. It feels Baroque but also strangely contemporary due to the pareidolia effect (the object appears to look back). Can you talk a little bit about this recent turn—the baroque techniques, the objects looking back?

SA: I’ve been making little still lifes with things like potatoes, piles of butter, pretzels. Inevitably, when setting up these little still lifes they start looking like things other than what they are. Perception is a condition of constant flux and I’m baffled by how complex, dynamic and changeable something is when you stare at it for hours, days or weeks. Figures and faces pop up without any pre-planning on my part and “stare” back, as you mentioned. I was initially uncomfortable with this and found it a bit corny, but I’ve come to embrace it. I think this has something to do with the human mind perceiving its own invisible construction. Painting is a mirror of one’s own hidden mind and, simultaneously, is a window opening to another. For me, the great contradiction and the great imperative of painting is that it’s a visual medium that conveys invisible content.

Sean Alward, Nightshade, 2019. Oil on panel, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Sean Alward, Nightshade, 2019. Oil on panel, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy the artist.