Described by the European press as a kind of wunderkind now hot in the eyes of European collectors, Omar Ba resonates with his vigilance toward the forestalling fortune of post-colony. Recently re-established in Senegal after a long exile in Switzerland, Ba recycles greyscale African idols alongside the technicolour phantasmagoria and hauntings of the postcolonial world.

His canvases look like: effusive circle cells constituting anthropomorphic dramatis personae of sloth-slayer dictators; ruminating/defiant African youth with their grey-shimmering and emergent sovereign selves; and gazes that penetrate the eyes of a European audience. And those gazes are not unlike Walter Benjamin’s comments about Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, where the titular angel’s melancholic eyes look at the past, perceiving not a string of events but rather the piling wreckage of catastrophe. But here it is Africa at the centre of Ba’s painted fields. Black underlayers, unseen to the viewer, might recall black obsidian mirrors. Masks float like talismans. Hallowed emanating lines jut out of heads like signs of madness or gifts. Painted phenomenologies of geopolitical madness. Lives caught in rhizomatic fields. The multiplicity of the fields (champs) are made by Ba’s repetitive and obsessive technique, one of exhaustion, which leads him to trancelike states.

We might also glean sites of postcolonial spectrality and socio-drama revamped and repurposed in primordial forests populated by beings that recall Amos Tutuola’s grammar of ghosts: “golden ghost,” “silverish ghost,” “copperish ghost,” “smelling ghost,” “homeless ghost.” Ba’s works show the stretch marks of the grossly overfed. Intrinsic in most of the pieces are permanent hybrid human-vegetal social webs and the matter that pervasively grows from them—that both feeds and deprives them. There are words and testaments of new world orders still complicit in the old game of empire. Always present are dictator patriarchs, still spinning webs of maleficent spells. Mimic-men, mandarins and wolfmen with monkey and plant faces lambasted and ready to sell. And finally, we are witness to stigmata, a whole heap of colourful stigmata.

Ba’s main goal might be that of an omniscient witness. Ba addresses not just the local effects of the colonial drip but also the larger web of the Anthropocene, and in that respect the words of Achille Mbembe seem apt to sum up some of the phenomenological animations we are witness to in and around Ba’s oeuvre, and which came through in our exchange: “the darkness of the night, an opaque mask and yet so penetrating, filled me every time with an indescribable fear, with their cohort of fireflies…each one smothered a ghost…it was said, to devour the meat of others, these songs with the taste of rust, salted from the corruptions of witchcraft this kind of squander, of perverse and excessive consumption, which survived the tears of the day and the ages of the world…silently, I wondered how I could ever build a speech on these graves, with their features so dry under the sun’s scythe, so obvious in their ochre colour, these graves so draped in their roll of shadow that they made me melancholic.”

Omar Ba, Eternal Resemblance 1, 2017. Oil, pencil, acrylic, ink and gouache on kraft paper with polyester foam. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo: Charles Littlewood.

Omar Ba, Eternal Resemblance 1, 2017. Oil, pencil, acrylic, ink and gouache on kraft paper with polyester foam. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo: Charles Littlewood.

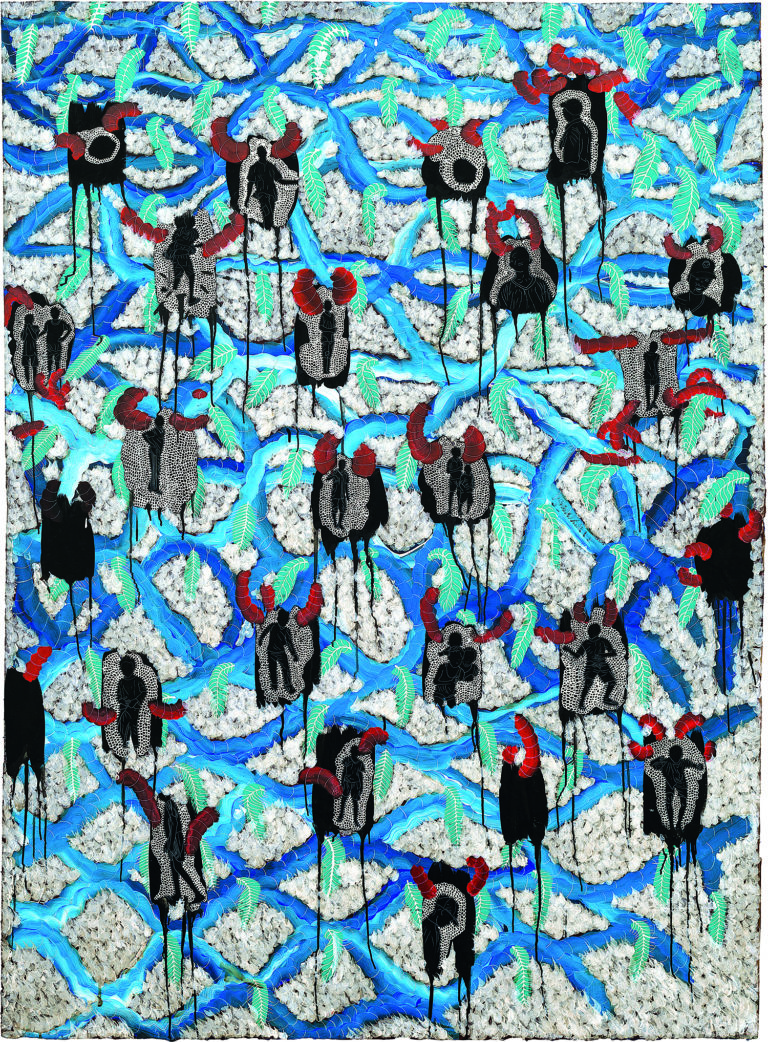

Omar Ba, Afrique, pillage, arbres, richesse (Africa, Looting, Trees, Wealth), 2014. Oil, gouache, ink and crayon on corrugated cardboard. MMFA, purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

Omar Ba, Afrique, pillage, arbres, richesse (Africa, Looting, Trees, Wealth), 2014. Oil, gouache, ink and crayon on corrugated cardboard. MMFA, purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

James Oscar: In the question period after your talk at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in June, there was no mention of the phantoms of post-coloniality that seem to infuse the canvases in this exhibition.

Omar Ba: I think that post-coloniality is something that does haunt us, and it is a concern for all Africans, because we don’t want to regress and to relive what our ancestors and parents experienced. Looking at the progression of things, sometimes we have the impression that we are turning in circles. We see that it is only terms and names that have changed; the system is still there and is now managed by Africans themselves. These ideas are very important in my work because I try to provide warnings, to arouse, to talk about these things that people tend to store away in the annals of oblivion. I’m trying to show it and talk about it so that debate can take place. It’s true that most people go to other aspects of my work (that’s what they’re interested in). I can’t blame them for that; their views are made in the same way that you saw certain things and are asking me certain questions.

JO: In the painting Afrique Now (2015), we see the words say “Who Shot This Man?” a reference to the “mysterious” murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of Congo after independence from Belgium. Would it be correct to say that your works show the persistence of a great contradiction, particularly the white elephant in the room regarding Lumumba’s post-colonial assassination?

OB: Yes, I am laughing because you are really getting into the opaque side of my work, the side of my work attached to my personal concerns, as in the similar case of the assassination of Thomas Sankara, the president of Burkina Faso [from 1983 to 1987]. Everyone knows who killed Sankara. But no one can tell you…in the end, it’s not even a debate. That’s what worries me. There are things going on and it’s unclear, but we pretend to move forward. In my work, I ask these questions again because I don’t want these people to be forgotten. You have to fight against this. Because there are things that can escape our memory because it may not suit us, but there are other things that strengthen us and I think that Lumumba should not be put in the oblivion of history. Sankara and Lumumba didn’t act like most of the current leaders, who are getting richer and richer. I don’t have any problems with people who earn their money properly but I also think we shouldn’t live in a country where there’s a lot of poverty. For me, it is these kinds of contradictions that we must try to resolve.

JO: In all the works there are effusive fields, usually of white feathers or what looks like cotton. In Identity and Roots I (2017), we see three of these fields around a young man’s head. It looks like centrifugal emanations and swirls.

OB: In my paintings, repetition is something important. It is something that reflects our repetitive identities, if I can put it that way. I have the impression that we are redoing the same things over and over socially and politically, so yes, there are repetitive fields and layers. When we think of the problems we are discussing, instead of solving them definitively we displace the problem and put another layer underneath or over it as if everything’s been resolved. So, I have gone on this quest of repetitive gestures. That is to say, all the paintings, all the textured treatment at the level of the characters, are repetitive gestures. The circle cells that make up the figurative characters are made through repetitive drawing. I spend days making these circles. I feel the need to repeat the cells until I feel exhaustion in doing these gestures. It can go from five to six layers then you have to fill it with a brush. To fill a surface with so many layers you have to repeat the gesture thousands and thousands of times. Sometimes I do them until I can’t hold my hand anymore. To make those little circles you find in the faces of the characters, you need deep concentration—it’s a kind of meditation. And for me, I meditate on my own problems, on the problems around me, on the problems of the world. I’m trying to find solutions. That’s why when I work, I repeat and come back and reflect at the same time.

JO: In thinking about these circle cells that make up the characters in all the works, I find that people referring to your work as figurative is reductive and exposes a false dichotomy between the figurative and abstract.

OB: Of course. I started with abstraction after studying at art school. What interested me was the form, the material, not social discourse. I preferred the transformation of matter, shapes and changes of colour in relation to the objects that are around. When I arrived in Europe, I noticed that when you speak, you get the impression that nobody listens to you because you come from Africa and you are different. So it’s like you’re not allowed to speak. I got the impression back then when you spoke about painting, there was even less interest. So I needed people to listen to what I had to say. I needed to say what I had to say. That’s why, and it’s important to underline, that I then decided to add figures on what were already abstract painting. I didn’t change much, I just put characters and I introduced the characters on the sort of painting I was already doing. If you just isolate an element of the present work, you land directly in abstraction.

JO: When you think of each of these miniscule circle cells that together form a face or a body, they still remain cells above being figurative representations. In reality, we are not complete forms, are we?

OB: But for me, it’s really a compliment and that reinforces what I am trying to do with my work because after all everything that exists on this earth is simply made up of cells. We are not complete forms. Man is made of cells and the proof is that when we disappear into the earth we become cells again. We become natural again and that’s also what stands out in my work. The proof is that during our lives we try to build ourselves and we gain experience and learn from our experiences. We build ourselves up as we go along, all the way, until we disappear.

JO: Beyond and meshed among the cells are also emanations: lines jutting out of the heads like antennas or frequencies.

OB: Yes, in fact, whether it is the characters I paint or the objects around the character, for me everything is linked. Every human being on this planet emits a kind of frequency. When there are wars, when there are genocides, they try to exterminate the population. We don’t even realize it but it’s like we were cutting ourselves off, cutting the limbs off our own body. Everything is connected in this universe. You can’t cut one part away to keep another part and live normally. If we do, we’ll realize there’s something missing.

JO: One of the things I notice in the paintings is that there are different gazes performed by your characters. In Identity and Roots I, for instance, there is what seems to be the pensive gaze. In Dommages collatéraux (2014), there is a direct gaze right into the viewer. But the gaze I find the most interesting is in Visa pour terroriste (2018). Here, I feel like I am I finally seeing the intruder’s gaze—a remarkable, penetrating gaze—coming from the young men wearing sunglasses. I like this idea of considering the gaze in art history. As Walter Benjamin writes of the angel’s melancholy eyes in Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, “His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.”

OB: The gazes in my paintings are not accidental. They are something that makes you think. In Identity and Roots I and Dommages collatéraux the gaze is from a person who seeks to show something, because the works are about history’s wreckages. Yes, here in Identity and Roots I, we’re talking about an observational gaze. Here, where you said that the gaze is thoughtful, one of ruminating, it is true that it is contemplation and rumination that I am presenting. I want a person who sees the painting to know that it is about contemplation and reflection. I want people to see through the breadth of the gaze that the character is resonating with reflection, contemplation and internal concerns. In some work, like Dommages collatéraux, I decided to show the factual. There the gaze is less one of contemplation and more a game that presents a balance sheet of sorts.

JO: In Visa pour terroriste it’s interesting that the figures wear sunglasses. I feel like I am looking at intruders and sovereign beings. I feel that these are the only paintings where I see people, beings, entities who could make a change. I thought of Djibril Diop Mambéty’s film Touki Bouki (1973), where young people ride a motorcycle with bullhorns on the handles and drive away, escaping. In Visa pour terroriste the young people are not polite or docile. They look like rude boys.

OB: Yes. Visa pour terroriste is a painting that speaks about the youth who are wrapped up in causes and problems that they do not control nor understand. All they may be concerned about is wanting to leave and defending causes that are not under their control. And that’s why if we look right into the sunglasses, we can see the reflections of where they are going. We can see their desire to go somewhere else. We see their reality from their own point of view.

JO: When we first met at the opening for “Same Dream” in Montreal, I spoke about a meta-textuality between your paintings and contemporary African literature. You immediately mentioned Alain Mabanckou. In his novel Broken Glass, a barfly professor sits at a bar with a notebook chronicling local history alongside a larger History. I feel like you are kind of that same person on your approach to your canvases.

OB: This character who frequents and practically lives in this bar is charged with recording the memory of this bar. I’m trying to do the same thing with my painting. I also try to stop at points and to capture time, and in doing so I also try to be moving forward. That is to say, I see problems and I try to solve them or to show them and move forward at the same time. Mabanckou’s Broken Glass is written, it is fixed. But here, it is painted, and time goes on.

JO: In another novel, Mémoires de porc-épic, Mabanckou presents an allegory about a porcupine who is the animal double of a human character named Kibandi, who sends his animal double on killing missions. Papa Kibandi put the spell on this human-animal double.

OB: I think that human beings naturally have an animal side and I think that civilization tries to distance itself from such an animality. We try to control our personalities so that we don’t look like animals. But when the animal side takes over the human side, we see the results: wars, massacres. People become animals and then there is the “You can kill your neighbour, you can slit a person’s throat.” Bombs are dropped just for a situation regarding a scrap of bread. I try to show the border where the human and the animal intersect.

JO: Yes, there is your series of paintings that shows various dictators with animal heads who also seem to look like sorcerers.

OB: All these depictions are ways of denigrating certain people, certain dictators, because for me the history of Africa has always suffered from how certain people, as soon as they are in power, do not want to leave. It becomes like a throne. That is why sometimes in my paintings you see medals that [distinguish] the dictators. Not medals that glorify them but medals with dog heads that denigrate them. But also inversely in the paintings, I [assign] medals to Africans who left and went to war, like the Senegalese Tirailleurs. They are the real heroes not listed in the annals of history. When there are ceremonies at the international level where we saw all the countries that participated in its conflicts, Africa is not represented, whereas in most of these conflicts, most of the African countries contributed food, money and soldiers. And in my opinion, African youth are not seeking reparations. No, I think we just need recognition. Because it is a recognition that can nourish and give strength. It is a recognition that can rebuild youth. Africa needs to tell itself that it is capable of doing certain things, that it is capable of going forward, that it is capable of taking charge. What I have mentioned are some things that might seem insignificant, but for us, it is very important because these are references that we need. Positive references.

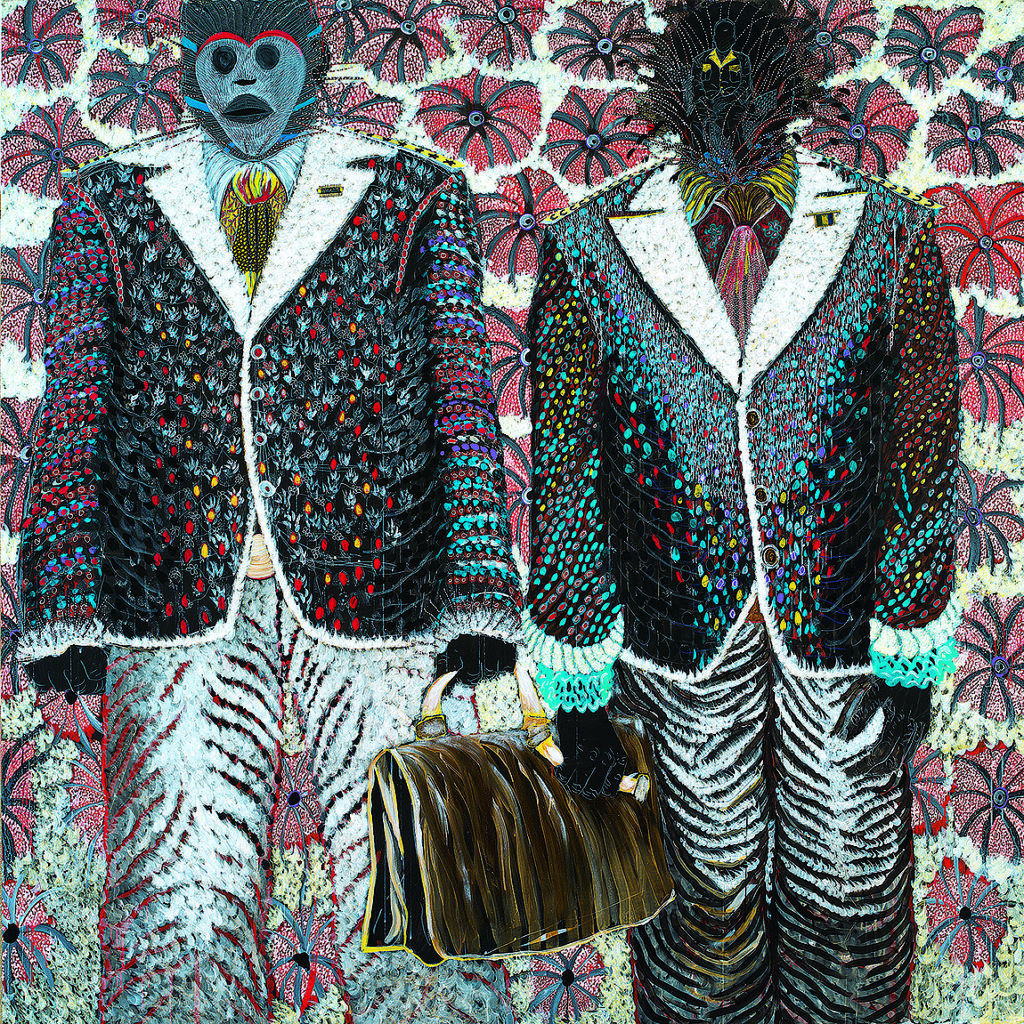

Omar Ba, Promenade masquée 1 (Masked Promenade 1), 2016. Acrylic, gouache, oil and pencil on canvas. JMD Collection, Hong Kong. Image courtesy Galerie Templon, Paris-Bruxelles. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo B. Huet / Tutti.

Omar Ba, Promenade masquée 1 (Masked Promenade 1), 2016. Acrylic, gouache, oil and pencil on canvas. JMD Collection, Hong Kong. Image courtesy Galerie Templon, Paris-Bruxelles. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London/New York. Photo B. Huet / Tutti.