Montrealer Paul Maréchal has a master’s degree in art history and a day job working as curator for Power Corporation of Canada’s corporate art collection. But he is better known to some—particularly those overseas—as one of world’s biggest collectors of Warhol’s record covers, magazine illustrations and posterworks.

In recent years, managing and documenting his Warhol collection, and related knowledge, has become a bigger and bigger part of Maréchal’s life. In 2014, he worked with German publisher Prestel on Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Magazine Work and Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Posters. In 2015, he and Prestel followed that up with Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Record Covers, which won an AIGA 50 Books Award and has gone through multiple printings.

This week, Maréchal’s collection was put in the global spotlight once again with the opening of “Warhol. Mechanical Art” at the Museo Picasso Málaga in Spain. “Warhol. Mechanical Art” puts numerous Warhol canvases and sculptures loaned by Tate Modern, MoMA and the Andy Warhol Museum alongside notable Warhol-designed albums and ephemera loaned by Maréchal.

Here, in a phone interview, Maréchal tells us what got his world-famous collection started, what he has learned in the process, and why, in his opinion, Warhol is any art historian’s dream subject.

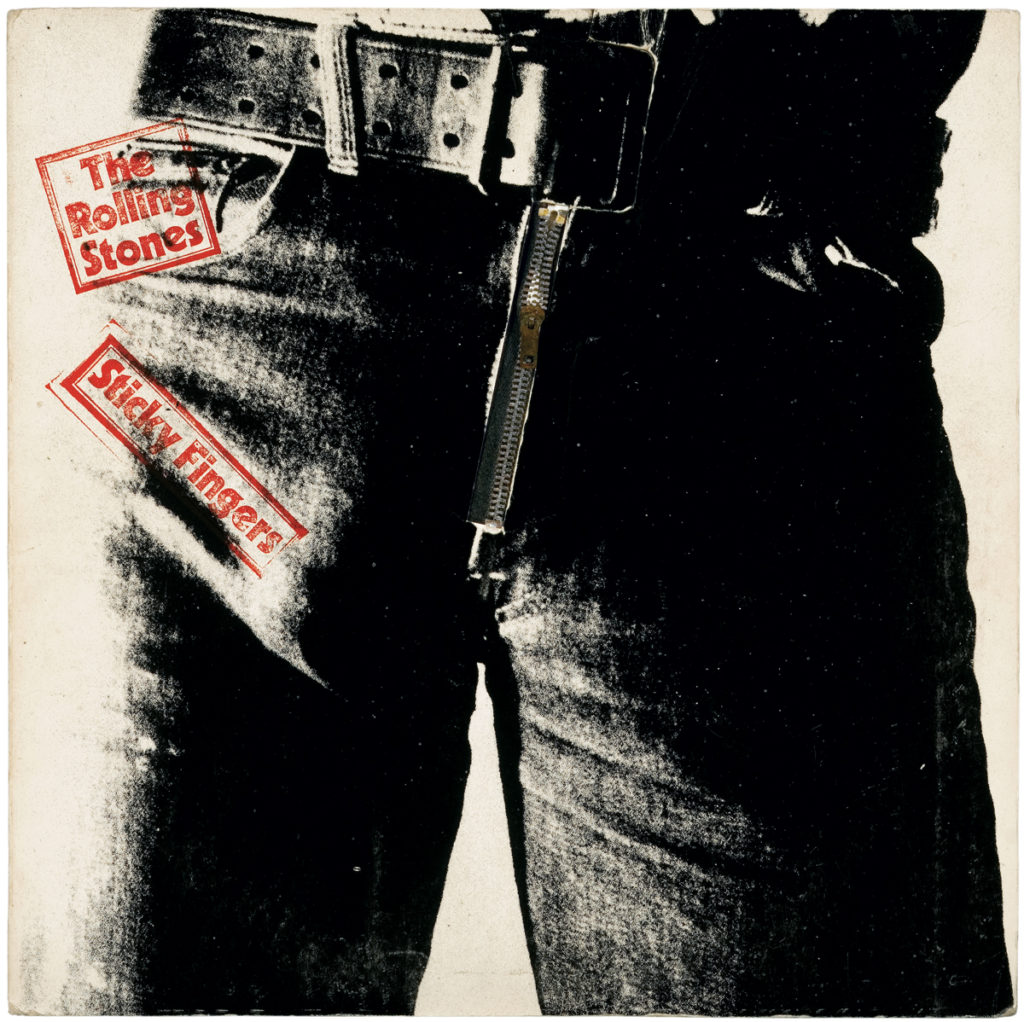

The Rolling Stones, Sticky Fingers, 1971. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: © EMI Group Limited. Promotone B.V. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

The Rolling Stones, Sticky Fingers, 1971. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: © EMI Group Limited. Promotone B.V. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Leah Sandals: I understand you started collecting Warhol’s printed matter in 1996. How did you start collecting Warhol’s magazines and records at that time?

Paul Maréchal: I first started collecting what I would label “Warhol graphic design works” as early as 1996, and it all started with the record covers.

Of course I knew, like most people from my generation, that Warhol created the two revolutionary record covers: one for the Velvet Underground and Nico self-titled album, with the peelable banana, in 1966, and the other for the Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers album, with the zipper you can open, in 1971.

My collection was based on an intuition: I thought that if an artist could come up with such a revolutionary record covers, it was because he had a deep knowledge of the medium—and therefore that he must certainly have done many of them.

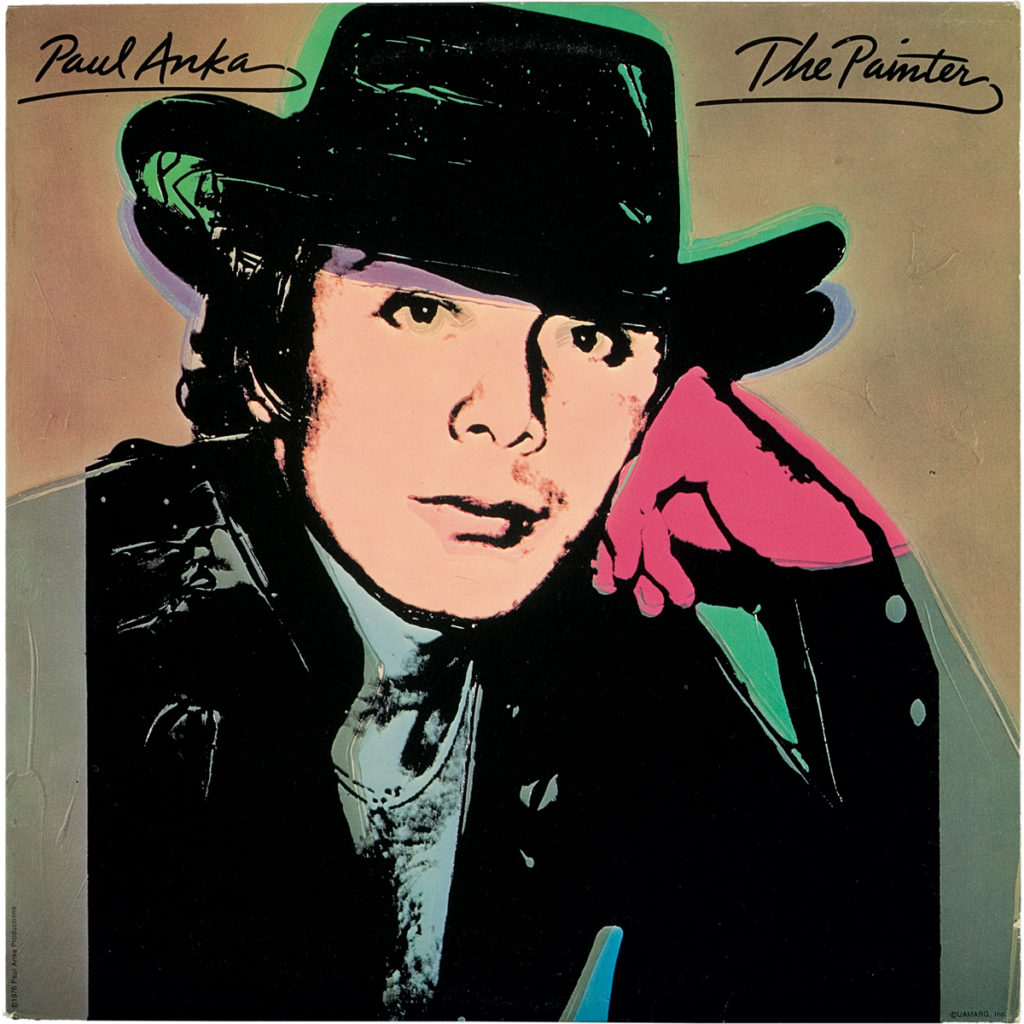

So I started looking for Warhol record covers at record stores in Montreal, Toronto, New York, Los Angeles and London. The first one I found was Paul Anka’s The Painter, from 1976, in a local shop. That was how it all started.

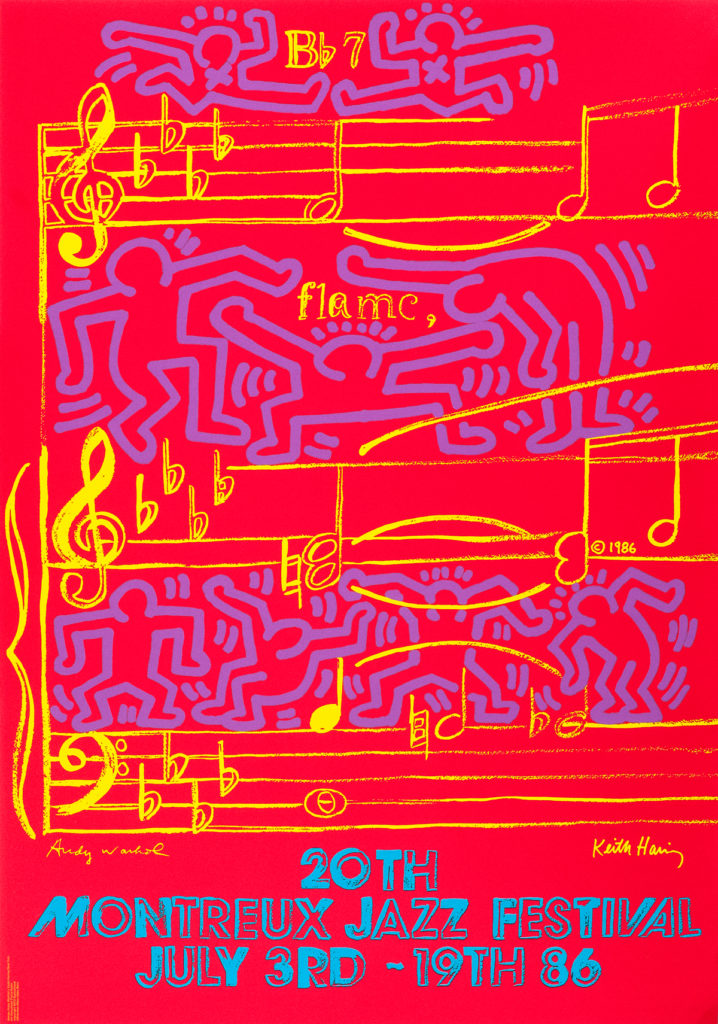

Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, 20th Montreux Jazz Festival, 1986. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal © Courtesy of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Roch Nadeau © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, 20th Montreux Jazz Festival, 1986. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal © Courtesy of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Roch Nadeau © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

LS: How did your collection grow beyond record covers into other illustrative material and multiples?

PM: Well, I continued the collection and my writings and my research looking for Warhols where you expected them the least—basically, seeking all the graphic-design works.

This includes works Warhol created for special events or special occasions, or, for instance, wine-bottle labels—he created four of them and very few people know about that!

There’s also the Christmas cards he did for Tiffany and Co. in New York, and the paper money he created, like one-dollar bills for a benefit auction held in 1971.

Warhol truly was the quintessential pop artist in the sense that he made art accessible to everybody. He graced dozens of record covers with his creations; he did a program for a dance festival in New York as early as 1954, barely five years after he settled down in the city. He did theatre programs, he did colouring books for kids, he did pharmaceutical brochures. So he truly made his art accessible—not only to museum-goers or gallery boards, but really to everybody.

After so many years of research, I can certainly say that Warhol truly was the artist who depicted the greatest variety of subjects in his works: be it a pop star, a package of cigarettes, a pair of shoes, it’s just amazing the variety of subjects. And he was also the artist who worked in the 20th century in the largest variety of media: film, Polaroid, fax, wallpaper, painting, serigraphs, lithographs, record covers, book covers, Coke bottles.

He even created three or four silkscreened paper dresses sold at some department stores in Brooklyn, and worked in textiles as early as the mid-1940s.

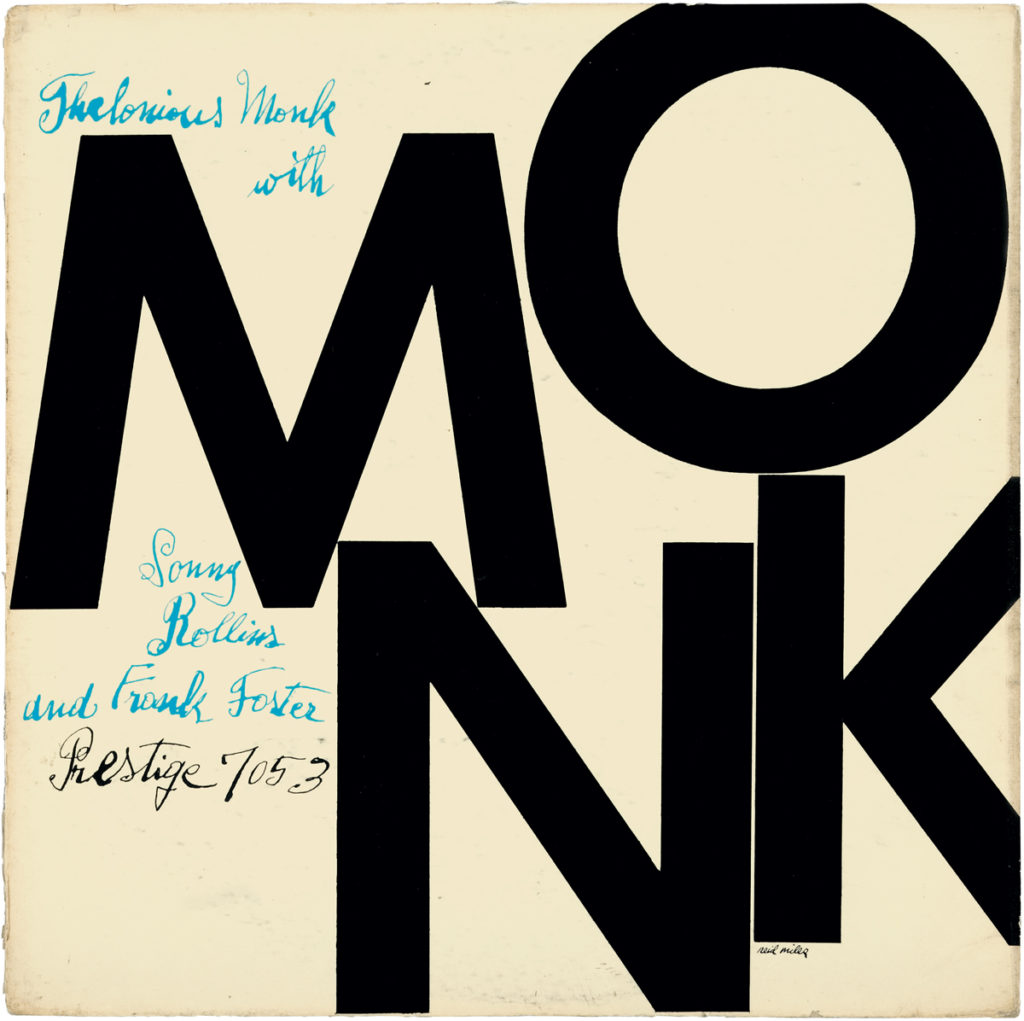

Thelonius Monk, Sonny Rollins and Frank Foster, Monk, 1954. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal © Reproduced with the permission of Concord Music Group, Inc. Photo: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Christine Guest. Rights: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Thelonius Monk, Sonny Rollins and Frank Foster, Monk, 1954. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal © Reproduced with the permission of Concord Music Group, Inc. Photo: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Christine Guest. Rights: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

LS: It’s now 22 years since you first started collecting these Warhols. What has sustained your interest over all that time?

PM: One of the reasons I kept collecting and researching Warhol’s works is because there has never been a dull moment. Warhol has often been where we expect him the least. Especially in the beginning, I would make discoveries every two or three months: a new record cover, a new poster, a new magazine illustration.

For example, in first 14 years of his career, Warhol was a magazine illustrator. I published a catalogue raisonné indexing every magazine illustration he was commissioned on—that was published in 2014, indexing more than 400. I keep looking for and researching new illustrations, and I’ve indexed 23 more so far!

Warhol is an art historian’s dream to study, because the variety of media is almost endless.

If you study Claude Monet, you will only study landscapes or oils on canvas. But Warhol is way more appealing for an art historian, given the range of media and subject matter—and challenging for an art collector as well.

Aretha Franklin, Aretha, 1986. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: SONY-BMG Entertainment. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Aretha Franklin, Aretha, 1986. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: SONY-BMG Entertainment. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

LS: Speaking of challenges to collecting Warhol, his prices have been big news in the art market this spring, with one of his Elvis paintings going for $37 million at Christie’s in May. What are the record covers and illustrations valued at, by comparison?

PM: Yes. Now, with prices going so high, it’s nice as a collector to be able to collect significant works by Warhol that are not in the multi-million dollar range.

In fact, in some ways, he remains an extremely accessible artist to collectors. The record covers go from $20 to maybe $20,000. The Paul Anka and Aretha Franklin covers he did can be found on eBay for as little as $20 each. But if you are looking for the silkscreen cover he did in 1963 for an album of artist interviews—the one with the big “$1.57 Giant Size” sign on the cover—that is between around $10,000 and $20,000, as he did only a limited number, and they are signed.

The rarest of them all is Night Beat, which was a box of three 45-rpm records of a radio-show pilot. I have the only known copy. How much is that worth? I have no idea. Certainly at least $15,000 to $20,000.

But you know, in terms of prices, even Night Beat is nothing compared to a $37-million painting by Warhol. And some of the record covers are as rare as Warhol’s other works; they have been printed in less than 5,000 copies. So there are fewer of some of those record covers than of the Marilyn Monroe edition—there are at least 2,500 silkscreens of those Marilyn Monroes circulating, since he did 250 editions of 10 prints each.

One thing that is also great about focusing on graphic-design works by Warhol, too, is that printing is so central to even his most famous works. Even the paintings—the start of each of his paintings is a photograph which he had made into a silkscreen at a printers’ shop at the size he wanted.

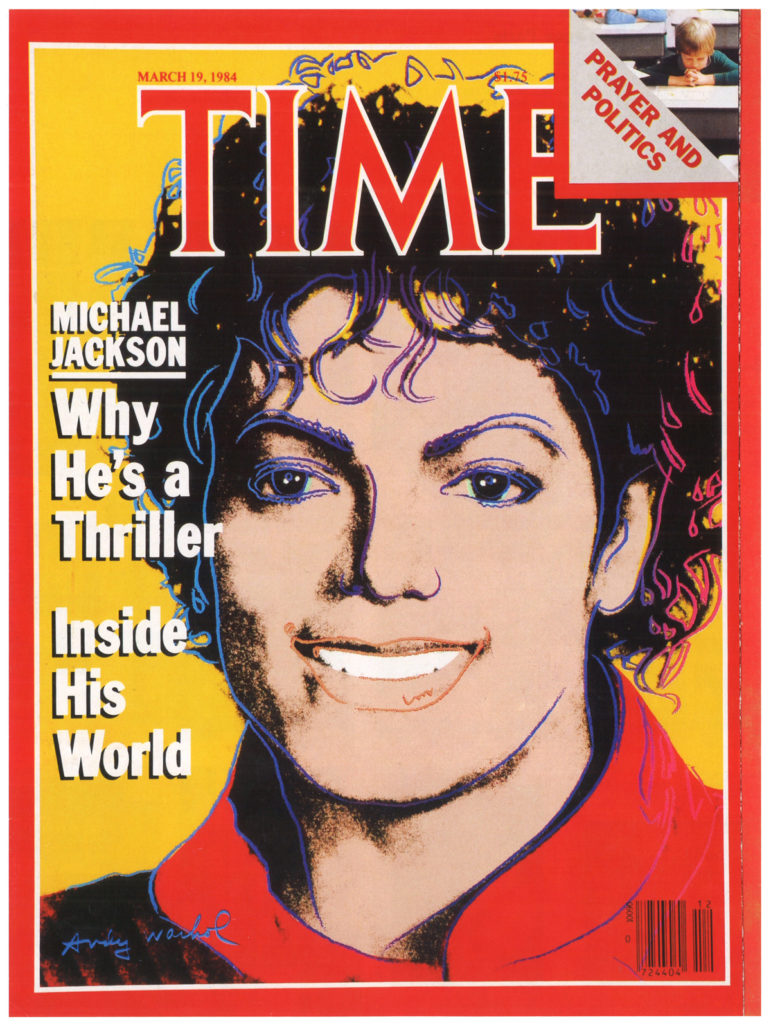

Time - Michael Jackson, 1984. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. © Courtesy of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Pierre Crépô y Denis Rainville. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Time - Michael Jackson, 1984. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. © Courtesy of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Pierre Crépô y Denis Rainville. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

LS: How do you store or display your Warhol collection in your home?

PM: I actually keep the collection in my office at work—because the collection is primarily on paper, and I live in an old Victorian home with ancient electrical. I worry about fire hazards, essentially, so I would rather keep all my Warhols in a modern concrete building.

I have more than 700 works in my collection, but since they are all works on paper, they can also be stored more easily in a small space like an office.

Also, I’m constantly lending works to museums, so the collection is rarely together. There are some 180 documents in the new Museo Picasso Málaga show, which was also in Barcelona last September and in Madrid in January. I’m also currently lending some 80 works to Musée de L’Imprimerie in Lyon.

LS: Do you have the collection on display in your office?

PM: Oh yes. I like to surround myself with the works I truly enjoy. It’s an inspiration.

And besides that, it’s important to me to be surrounded by works I have been collecting. By looking at some works on a daily basis you, at some point, tend to see something you didn’t see before. It is a very meditational process.

The official opening of “Warhol. Mechanical Art” at the Museo Picasso Málaga, featuring multiple album covers, posters and magazines from the collection of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Facebook.

The official opening of “Warhol. Mechanical Art” at the Museo Picasso Málaga, featuring multiple album covers, posters and magazines from the collection of Paul Maréchal. Photo: Facebook.

LS: What’s next for you?

PM: I still have to complete the catalogue raisonné on Warhol’s book covers. I also have an idea for another catalogue raisonné—this one on Warhol’s textiles, because that has never really been explored in depth by any author.

The Tate Modern is borrowing some works for its Warhol show in 2020, and other curators continue to visit the collection.

Overall, I hope that my research has helped make another important side of Warhol’s works available to the the public. There is just so much more to Warhol than what people know.

“Warhol. The Mechanical Art,” containing more than 100 pieces from Paul Maréchal’s collection, is on view at the Museo Picasso Málaga in Spain until September 16, 2018.

Paul Anka, The Painter, 1976. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: EMI Group Limited © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.

Paul Anka, The Painter, 1976. Paul Maréchal Collection, Montreal. Photo: © Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Christine Guest. Rights: EMI Group Limited © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP, Málaga, 2018.