This interview with Shelley Niro was part of a cyclical, intergenerational conversation that transcended the time and space we shared. When I asked Niro if she had any intergenerational knowledge to impart, she spoke of Willie Dunn’s song “The Ballad of Crowfoot,” a song to which the title of this interview refers. The way Dunn used music and archival footage to create an Indigenous narrative inspired Niro as an impressionable, emerging creator. Dunn made apparent to Niro the radical possibility of film and photo—coincidently, this is how my generation of creators feels about Niro’s work.

It would be easy to assume that Niro’s work is somehow understatedly or quietly political and, in doing so, dismiss the decades Niro has spent psychically, physically and materially taking back occupied territories, one laughing Native girl at a time. “Native” is a word used by older generations to describe Indigenous communities, a word which I’ve decided to use here out of respect of Niro’s use of the term. There is refusal and acknowledgment in the usage of “Native,” too. Namely, settlers are afraid to say it, and it’s what the common folk (myself included) tend to call one another.

In a political climate where the consequences for loving one’s own Native womanhood a little too freely could be fatal, and wherein Indigenous communities and settlers alike have adopted nationalist rhetoric to define Native political thought and erased the relational teachings encoded in traditional instructions, love is a political act. Native love has the power to topple nations of white men. Love lives in Niro’s most recent retrospective, now on at the Ryerson Image Centre, as a liveable form of Indigenous ethics. Niro’s work exposes the performative–stated rather than lived and acted upon–nature of Indigenous political thought that misaligns itself with masculinist conceptions of Indigeneity, that sees politicization in warring with the state, but not in the laborious work of loving Native communities to ensure their survival into the futures Indigenous philosophers wax poetic about.

Lindsay Nixon: I guess the obvious question is, how does it feel to have a retrospective at this point in your career?

Shelley Niro: It’s so cool. It feels so great. I’m so happy.

LN: Did it evoke any emotions to have to look over your body of work like this? And what was your thinking in bringing all these works together?

SN: It’s always emotional because sometimes you don’t look at the work. Like for example Chiquita, Bunny, Stella (1995)—I made that piece and then sent it off to Thunder Bay in 1995. I’m just seeing it again now because Thunder Bay purchased it and it’s been there for a while.

LN: So this work is all borrowed or is some of it from your personal collection?

SN: Some of it is from my personal collection. Like, Flying Woman #5 (1994) is from my personal collection. Bread and Cheese (2004/2017) is from my personal collection. My Girls (1999) and Chiquita (1999) are from my personal collection.

LN: That’s cool to know that the show is a mix of collected works and your own personal collection. I think that your work has talked about how Indigenous femininities have been so alternative to settler femininities. That means there are particular kinds of stereotypes that get placed on Native women because they don’t ascribe to white femininities. I’m wondering how you see that playing out in your work.

SN: I’ve always been aware that the Native woman’s female image has been commodified. It’s like, “We only want to see these kinds of images reflected of Native women. And if it’s any other kind of images, we’re not interested.” I really think it comes back to the murdered and the missing. They kind of don’t care. It’s really about having those images out there in the public, and people seeing. It’s like breaking that barrier where people see images of Native women and it becomes more approachable. I just think that people don’t want to see Native women the way we are. But I think that might be changing too. It comes down to film, Native women in film, and the so very few images of Native women. It all has to change because we’re so much fun!

[Laughter.]

LN: So you see the work in this show as a reclamation of Native womanhood in all its facets?

SN: Yeah, I think so. It’s making positive imagery that people can see, relate to, and not be afraid of. Recognizing that Native women are out there.

LN: There’s something happening with my generation where we want to look at images like The Shirt (2003) and ascribe our own identities to them. I feel like when we look at positive womanhood that isn’t so “feminine” we think about queering these images, or ascribing queerness and non-binary genders to them. If that wasn’t the intention in how you made the work, how do you feel about us now looking to it and ascribing queerness and non-binary genders to it?

SN: I guess that is a tricky question because I don’t specifically make queering images. Although my friend in this photograph is, you know, gay.

[Laughter.]

I like to make images of women who, you know—for years and years and years we’ve worked in food orchards. We worked picking berries. We worked in tobacco fields. So we’re always dressed in a particular kind of way. We’re ready to work.

[Laughter.]

Back in the day, you know, we didn’t have money to really buy the clothes that we might have wanted to. So it just comes down to, “What can I afford? What can I work in?”

LN: Do you have any favourite emerging artists?

SN: They’re all great! They’re all so bold in their expression of using visual art. I think it’s true! I think every time I do see something [from an emerging artist] I think, that is so great! They’re really using that visual language to say something they want to say.

LN: Artists creating right now, like Dayna Danger, are really going out there and using bold visual language to talk about relationships. But I think of your work as the O.G. of talking about sisterhood and “girls just want to have fun” Native feminism, and creating long-term creative kinships through collaboration and people you’ve photographed. Do you want to talk about people who were consistently in your work?

SN: I used my friends and family. I used to really concentrate on putting them in the work. When you work in the darkroom, you spend many hours in the darkroom. Sometimes you have to divide yourself between the darkroom and your family. I thought, well, if I have images that have my family in the work, it’s sort of like having them with me. It just gives me greater impetus to finish the work—and to put some love in the work, as well, which I think is so important, to make [love] a part of the recipe of artmaking. You have to love what you’re doing or you’ll not finish stuff. You kind of won’t care about it.

LN: When you were creating in the 1990s, did you ever feel like your work was received differently than work that was viewed as being hyperpolitical?

SN: That question always comes up because I don’t purposefully make political work. But I think being a contemporary Native living in Canada, I just think it’s a part of our daily living. It’s always something we have to contend with. Even though I say that I don’t make part of the work purposefully, I find it’s there anyway. If you just make work, it’s there. Even taking photographs of flowers would be a political statement on its own. I just think it’s just part of the equation.

LN: I know that photography has been a medium that Indigenous women have returned to again and again to assert what Jolene Rickard calls visual sovereignty. I’m wondering, why photography? Are the materials you use and how you use them political to you?

SN: I always go back to the very beginning of my own life and how resources were so limited. It’s like, do I get the fibre-based paper or do I get the RC paper? It was almost always the RC paper because it’s cheaper. It’s trying to find how you can make the most beautiful image you can, on a limited budget. Trying to figure out, How can I do that and be happy with what I’m doing? If I had all the equipment in the world back then, I don’t know. I don’t know what I’d do.

LN: That is such a metaphor for creating as a Native person.

SN: Yeah—exactly.

As you notice, in some of my work I have beadwork. It’s like, I can’t afford to do anything, I’m going to do beadwork now.

LN: It’s interesting to see the beadwork and dolls present in the exhibition. I feel like people often associate your work with photography. Why does bringing those objects into your practice make sense?

SN: Those [dolls] are made by the people [in the photographs] they are in front of, and part of an installation [Chiquita, Bunny, Stella (1995)]. Native people always get the rap that they are sucking the government of all their resources, that they’re all on welfare. Native people are seen as taking from Canadian taxpayers. We contribute. We work hard. [That installation] is my way of saying we’re working as hard as we can. Maybe we don’t have the same opportunities to get the same kinds of jobs other people can. But, in our own way, we’re working hard and contributing.

LN: There seems to be an incredible amount of intimacy in the installation of those dolls adjacent to [those photographs]. That it’s not just work. It’s careful work by grandmas and aunties.

SN: I just like what they do. I just want to show that it takes a long time to make something. Until we get the price we need for beadwork… You know, it’s still considered to be low-rung.

LN: It’s kind of ironic, isn’t it. Because it’s such a laborious process.

SN: Not that I want the price of beadwork to go up.

[Laughter.]

LN: How were your relationships and kinship important to your overall practice?

SN: Really important. When I look at the photographs, I like to think that the people in the photographs are my friends and my loved ones. It becomes a bonus, having Native people in those images…. We weren’t really a part of the image-making, say, 50 years ago. I’ve looked at Hollywood films. It’s so cool to know that these people are now archived forever in film. Now we’re participating more in film. I wanted to make sure some of my family were archived and we could look back at those images 50 years from now and go, “Oh, remember when I looked like that. Look how skinny I was.”

LN: You’ve created a really beautiful consistency to your work because it seems like you photograph certain people again and again, as they grow through time. Is this intentional? Are you wanting to explore their journeys?

SN: If I have a positive experience with people, then I like to include them again and again and again.

LN: I’ve seen the contemporary readings of your work as feminist. I know older generations of women in my family really refuse that title. But that my generation seems to be reclaiming it. I’m wondering what you think about that label being ascribed to your work?

SN: It’s a funny word. Twenty years ago, feminism meant trying to be like a guy in the workforce, and taking on all that power, and using that power to have your own influence wherever you are. I like to say, “Yes, I’m a feminist.” But it’s more about equality. It’s more about seeing people and trying to create a balance with everybody around you. I’ve been in situations too where it was the style to be really hateful towards men. It’s like, I don’t get it. I think being a feminist is a good thing. A Native feminist is a better thing.

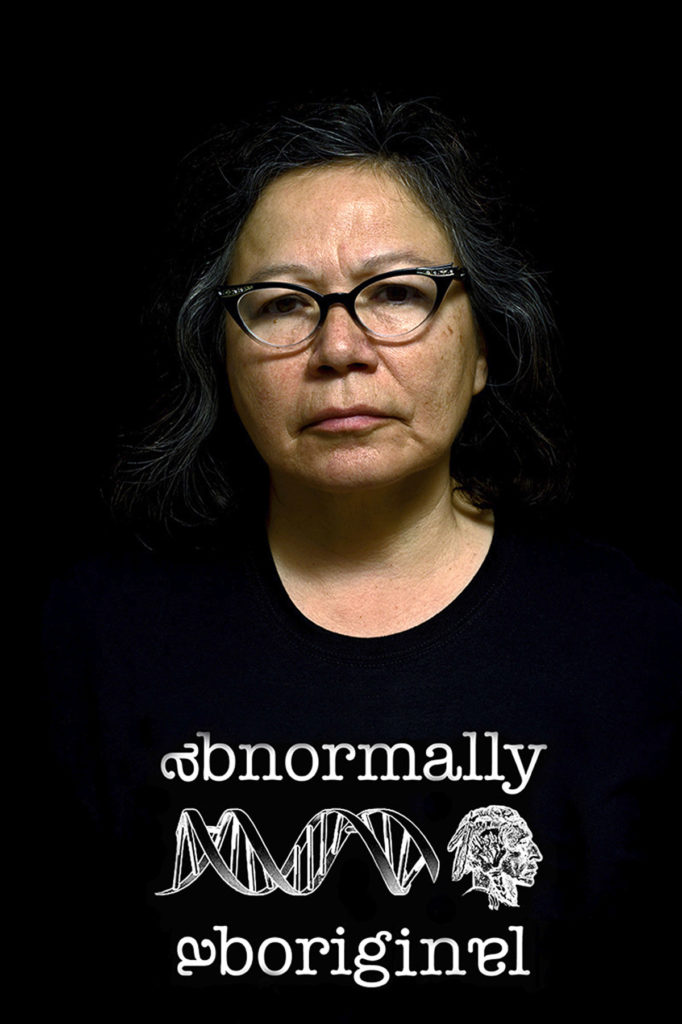

Shelley Niro, Abnormally Aboriginal (detail), 2014, inkjet print on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Shelley Niro, Abnormally Aboriginal (detail), 2014, inkjet print on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

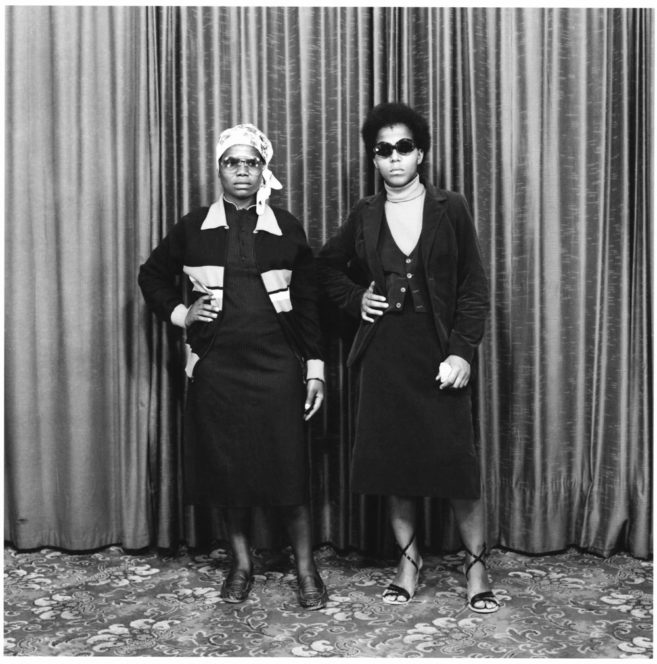

Shelley Niro, Mohawks in Beehives I, 1991, gelatin silver print with applied paint. Courtesy of the artist.

Shelley Niro, Mohawks in Beehives I, 1991, gelatin silver print with applied paint. Courtesy of the artist.