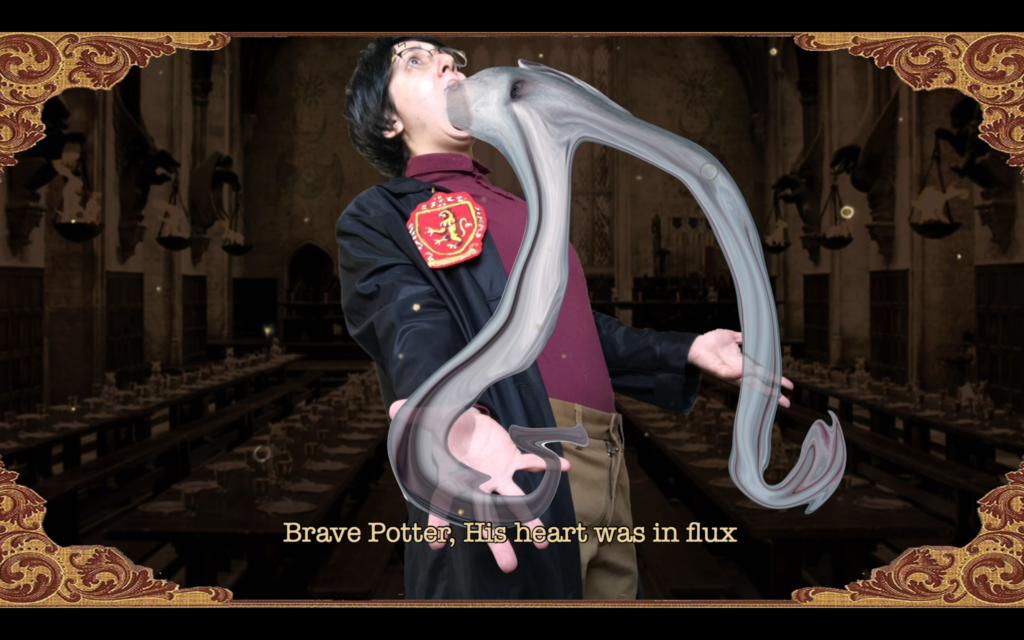

Maya Ben David is best known for her pantheon of cosplay characters, particularly the “anthro” plane in Air Canada Gal (2015–) and the gargoyle-esque red gym bag in Pocket GoodLife (2017–). Mold Maid personifies a piece of bathroom mould as a tender-hearted nanny. Other works puncture the surface of pop culture to reveal its profundities. Harry Potter and The Unborn Child—a video in which Harry Potter becomes pregnant by swallowing his archenemy, Voldemort—celebrates the often marginalized fan tropes of mpreg (male pregnancy) and vore (vorarephilia, the act of swallowing something whole). Pokémorph Me presents an interspecies fantasy in which the artist becomes a buff Charizard—what the video’s voiceover refers to as a “sexy Pokémorph.” Ben David’s work suggests that we could all become more imaginative and compassionate by diving into weird zones with unironic enthusiasm. I spoke to Ben David about her engagement with fan culture and the complexities of approaching this material from an art perspective.

Maya Ben David, Anthro Plane: Air Canada Gal (still), 2015. 48 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Ben David, Anthro Plane: Air Canada Gal (still), 2015. 48 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Katie Connell: For me, fandom has always been this unique outlet for channelling particular intensities or obsessions in a way that feels expressive. I didn’t see it legitimized by the art world for a long time. How would you describe your relationship to fandom, fan fiction and fan art?

Maya Ben David: I didn’t get into fan fiction until my later life. I didn’t really know it existed. I was afraid of my computer for a long time because I watched this episode of Are You Afraid of the Dark? where a computer has a virus and then it comes and kills you.

So I didn’t know what fan fiction was, but I was always a huge fan. I always imagined, wrote and talked about it with my friends, but I didn’t know it was an actual, magical, incredible world. There is something special about it that isn’t there in other kinds of mediums. When you go on YouTube and you see somebody quickly make an animation of what they think two characters should be, there’s something so exciting and spicy about that. When I saw stuff like that, I got really into it.

Maya Ben David, Mold Maid, 2019. Performance still. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Ben David, Mold Maid, 2019. Performance still. Courtesy the artist.

The only way I can really get into something is if I’m very emotionally invested or I’m exposed to it, and it takes over as a very intense emotion in my body or brain. For example, I’ll get a table from IKEA and then realize it’s off-gassing all this formaldehyde. I’m upset about that and research it, and think about what off-gassing is. Then I think it could be something like a hot girl trying to poison me.

KC: I’m curious about that impulse to anthropomorphize something like off-gas or mold. Mold Maid, for instance, characterizes a lot of empathy for nonhuman entities or objects. What do you get out of anthropomorphism?

MBD: I think it’s this tenderness toward things that are scary. When you resist something like that, it feels very uncomfortable. I had mold that kept growing on my hair conditioner and I cleaned it all the time but it never went away. But when I started finding it adorable it became wonderful. It feels like you have a little friend with you. Anthropomorphizing makes you feel like you have special friends hanging out with you all the time.

KC: The first piece of yours I came across was Harry Potter and The Unborn Child, which was commissioned earlier this year by Rea McNamara. Part of the appeal of your work is how online communities can slip into weird, funny zones. You’ve been emphatic that you’re entrenched in fandom, but as its language and codes enter mainstream discourse there’s an increasingly fine line between celebrating and fetishizing fan subcultures. Do you see this as a line you have to walk as an artist?

MBD: Definitely—with that film [especially]. I do think it’s really important to [show] this is something that’s happening in fandom, but we can’t treat it like it’s a weird thing. There’s even that trend of drawing people with engorged knees. It does seem bizarre, but there’s obviously a reason for it and there’s obviously interest in it, so it has meaning and has importance. It’s good to be playful and fun, but it’s also good to ask, “Why is this so interesting?”

Maya Ben David, Harry Potter and The Unborn Child (still), 2019. 10 min 59 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Ben David, Harry Potter and The Unborn Child (still), 2019. 10 min 59 sec. Courtesy the artist.

KC: For Harry Potter and The Unborn Child, there are a number of subversive fan tropes you could have drawn from. What do you find particularly appealing or useful about mpreg?

MBD: I tried really hard to be very tender with mpreg and give a lot of reasons for Harry being pregnant. It was important that I wasn’t making fun of something like that. Pregnancy is very interesting in general because something gross grows inside of you and it feeds off of you. You have this bond. Sometimes when something feeds off of you it’s bad, and sometimes it’s good. It’s how you view it: as a parasite or as a magic thing.

I like to think about vore, the idea of eating something you desire whole, and you become pregnant with that thing you desire so much and maybe even birth it. I also like pregnancy being seen as not just a heteronormative thing. Male pregnancy is a trope in fandom but also possible in real life. Even though my work is more about vore pregnancy, it’s important for me to pay respect to where mpreg is coming from.

KC: Fan fiction and fan art often draw out existing dynamics in a text that are implicit or hidden. This piece made me reflect on the way Harry’s relationship with Voldemort is written in the books as a type of psychic possession. In this way, maybe Harry has always been pregnant with Voldemort?

MBD: I think about that all the time! Voldemort’s literally in his head: Harry sees what Voldemort sees in his dreams. Harry’s always getting physically moved by Voldemort: he has crippling pain. I had already been really into Harry Potter and had been thinking about how important Harry’s scar is and how Voldemort is already inside him. So Harry and being pregnant came together. I was [having conversations] about mpreg and I wanted Harry’s pregnancy to be a bit mysterious and like vore. A lot of my characters consume things whole. Airplane Gal has become pregnant before, so my characters being pregnant is not uncommon for me. I made Moses pregnant from God.

“There’s a reason popular culture is popular and that’s because it moves a huge amount of people…For us to disregard this huge interest, I think, is a large fault of ours. We’re missing out on something special.”

KC: This work reminds me of the YA author Rainbow Rowell, whose recent books began as fan fiction about Harry Potter characters Draco and Harry (Drarry), and of Florida Man, the drag queen who performs as Lady Voldemort. There’s a great deal of warmth and affection for your source material. What first appears as parody quickly becomes a thoughtful, developed story.

MBD: I always think about what happens to Harry after [the books end]. In general, he has a hard life. So I thought, after all that had happened, he would kind of get to rest. But then, how does [everything] get digested by him? I guess this piece came from thinking about his pain.

The story is actually quite mundane compared to the original Harry Potter. I really wanted it to stay unexciting. People were upset in the comments like, “This didn’t really go anywhere.” But I wanted to just give Harry a comforting experience where he had to do something scary, but all his friends were there. He got snacks. He was worried about who was going to take care of him, but it turns out the doctor understood his situation. I wanted him to feel safe: he’s going to give birth and it’s going to be okay.

“I think it’s hard to express yourself. It’s fair that people read things into my work, but it’s scary that people already make lots of assumptions about my work, about my sexuality.”

KC: Some of your work is about interspecies erotics. In Pokémorph Me you transform into a sexy Charizard, the final evolutionary form of the Pokémon Charmander. What is it about Charizard that draws you in?

MBD: Charizard is very indignant. [His human owner] Ash loves all the different iterations and evolutions of Charmander. At first, Ash saves Charmander from an abusive owner and they have a very tender bond. Then Charmander becomes Charmeleon, who is really powerful, but when he becomes Charizard, he doesn’t like Ash anymore. He no longer wants to be in this system of servitude.

I also like how he’s very masculine. Charizard is a dragon and he’s always kind of coded as male. I wanted to put my own body onto Charizard and give a different story.

KC: I feel quite protective of these niche subcultures that contemporary art has recently found so interesting. How do you protect the communities you draw from?

MBD: I think being loving is a very important part of it. In Pokémorph Me there’s a voiceover where a person asks: “What are your sexiest Pokémon? What Pokémon do you dream about at night? What Pokémon light your fire?” [Reacting to these ideas] like, “Yeah, I want to know the answers to these questions,” and then participate in answering them.

Something I don’t like is that some people take a drawing of a sexy anthro or furry and put it in the context of ‘Look how weird or maybe problematic this is.’ But someone just made this online—it’s their fantasy and a beautiful manifestation of their desire.

I think the terminology you use [is important]. Lots of people use artspeak when they’re talking about furry things and fan art. I think it’s good to actually not use artspeak. That’s why I like to say, “I think that’s so hot.” Instead of saying “breasts,” I say “boobs,” because when I’m talking about these things I want it to feel very relatable, or in the same tone as the people who made the things or the world that I’m talking about. [That way] you don’t isolate your selves from those people.

Maya Ben David, POKÉMORPH ME (still), 2016. 6 min 20 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Ben David, POKÉMORPH ME (still), 2016. 6 min 20 sec. Courtesy the artist.

KC: There’s a lot of imposed shame or embarrassment associated with being a fan. Do you feel that your work counters this?

MBD: I try to be very open about it. It’s still kind of embarrassing for me. I still feel afraid to do certain things. I read the comments on my YouTube videos and they’re very bad: people tell me to drink bleach and stuff like that. There’s still a lot of resistance to my work. But there are also a lot of nerds around, people popping up their heads and being like, “I like this!” So I’m able to stand more in a collective of people who like these things. I’m trying, but it’s still scary. I’m definitely not that courageous person. I’m afraid.

I’m even afraid to make things too queer; I think it’s still scary to make stuff that’s too weird or too sexy. Those can be together sometimes. I feel stifled and nervous to do those kinds of things. I think it’s hard to express yourself. It’s fair that people read things into my work, but it’s scary that people already make lots of assumptions about my work, about my sexuality. Everything I put out adds another layer to that. I guess I don’t want to give people too much about myself.

KC: Most fans are anonymous or use pseudonyms. You kind of take off the mask or avatar that a lot of fans get to have. That raises the stakes.

MBD: Yeah. I’m not as protected, so I need to have a lot of shields.

KC: In MBD vs Jon Rafman you talk about how the score for the movie Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) made you cry. Do you think it’s easier for art to be ironic about pop culture rather than moved by it?

MBD: There’s a reason popular culture is popular and that’s because it moves a huge amount of people. So many people are going out to the theatres and watching Batman v Superman and getting this collective experience. For us to disregard this huge interest, I think, is a large fault of ours. We’re missing out on something special. There is something really special that happens in [superhero] movies that art doesn’t get all the time. I do think it’s important for us to pay attention to this because obviously so many people are feeling strong emotions toward it. We keep talking about art, and the history of it. But if we want to connect with other people, then we need to look at what other people are liking. I put a big emphasis on that for myself, and I don’t feel shame for consuming anything that’s delicious in popular culture.