A few months ago, I went to see “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” at the MAI in Montreal and I left with a few questions for the curator, Jamie Ross. First, the communications stated that the exhibition is “proudly” presented as part of Pervers/cité, an anti-capitalist queer festival that, for more than 13 years, has run concurrent to the more mainstream Montreal Pride festival and, as the exhibition text notes, “connects the radical political underpinnings of queer movements to the ongoing struggles in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal.” “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” worked in a similar vein. It brought together elements from Ross’s research, on behalf of Média Queer (a Canadian online catalogue of LGBTQ Canadian film, video and digital works, their makers and related institutions) from the collections of VIVO Media Arts, Vidéographe, Archives gaies du Québec, The ArQuives (formerly the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives) and Artexte, and from the personal collections of members of the Front de Libération Homosexuelle. The focus was on documents from the period in which sodomy was, on paper, decriminalized in Canada. These documents, including magazines and tracts, banners and films, were complemented by recent works from contemporary artists Hazel Meyer, David Widgington and Projet Hybris. Ross’s “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” is actually part of a larger project operating under the general banner of 69 Positions, with shows and programming in Vancouver and Toronto. As the project website states: ““69 Positions” transports you back in time to the highpoint of the sexual revolution, in a tripartite collection of media, memorabilia, ephemera, and documentary films.” Ross was interested in bringing a critical eye to these national celebrations, since the legalization of the act did not actually amount to the decriminalization of queerness. For example, gay cruising sites today continue to be sites of harassment and policing. Arrests of gay men for “public sex” occur with shocking frequency. I speak to this issue as an outsider: as a straight white woman, my sexual identity is not criminalized or prosecuted, yet I recognize that the reality of being out and queer in 2019 is far from the idealized utopia (think of the “love is love” hashtag) that the media and our government try to convey.

As a curator Ross entered into the project knowing it could never represent a complete picture of the activist work that lead up to, and followed, the 1969 decriminalization of sodomy. Still, the project attempts a nuanced depiction of the moment of decriminalization paired with a political acknowledgment of the ways in which decriminalization has not led to acceptance or safety for LGBTQ2 folx. In addition to being a curator, Ross is himself an artist, and his work is deeply informed by his pagan spiritual practice. As curator, Ross’s interest in the archive was clear, yet there are unique ways in which he works with notions of the archive beyond what is typically sanctioned. Any follower of Ross on social media will have witnessed his acts of seed saving, the results of which are then used in other projects. For Ross, seed saving is an act of remembrance and of imagining the future at the same time, so in this way, I conceive of his work as an archive.

I had originally hoped to produce a typical interview, because when I left the exhibition I wanted to know more about what was presented and what wasn’t. Who, and what stories, were left out of the original archive? Which ones were highlighted or ignored for the creation of this exhibition? But Ross suggested I open the conversation up, beyond the exhibition, to include a variety of voices from artists working on similar issues now, including Jade Yumang, Hazel Meyer and Tobaron Waxman. Each was invited to participate here, in part because, had Ross been given carte blanche and a larger budget, many more artists could have been involved in the original exhibition. What follows is a distillation of our conversation, where each artist discussed aspects of their practice in the context of larger issues around queer visibility.

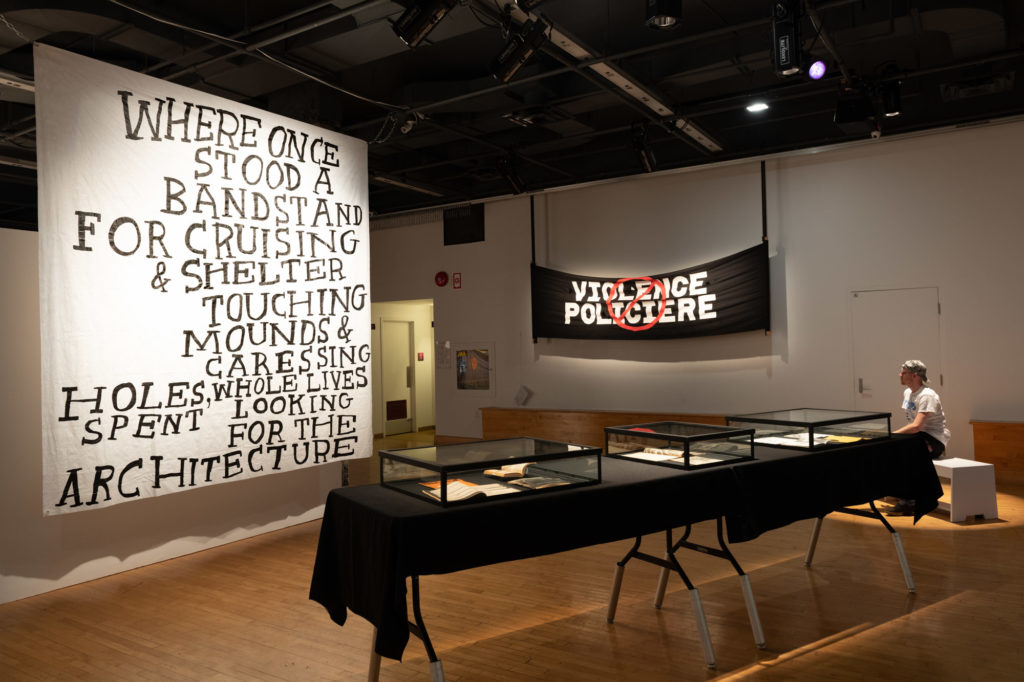

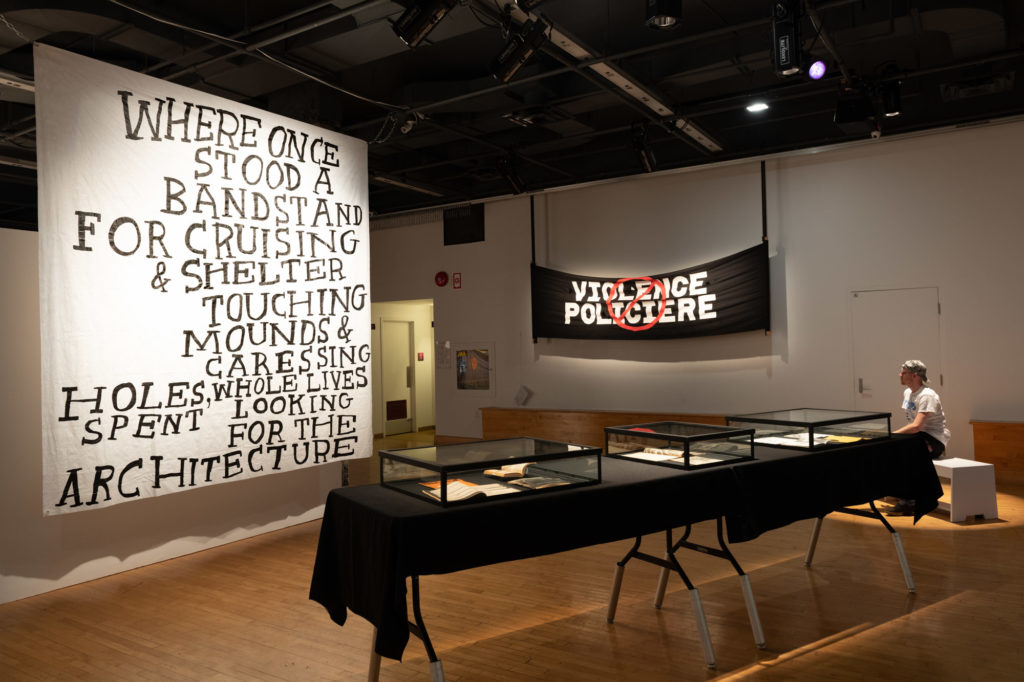

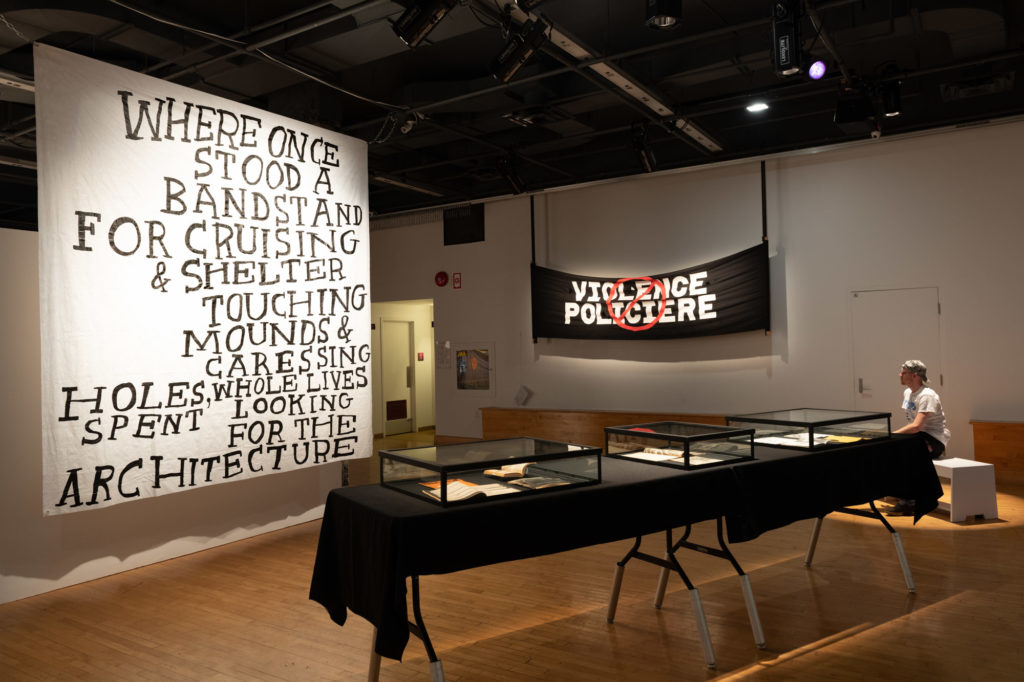

Hazel Meyer, Where Once Stood A Bandstand for Cruising & Shelter, 2017. Paint on Tyvek; Anonymous creator, Police Brutality, 1990. Banner courtesy les Archives Gaies du Québec. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland

Publications from the collection of the Archives Gaies du Québec: Roadside Sex (circa 1970), Sean; A Case Study: Headhunters: A Complete Study of Sexual Practices in Public Restrooms by the Male Homosexual (circa 1970), Christopher Ford; Homosexual Sex Techniques (circa 1969), anonymous; The Homosexual Health Guidebook (1970), QQ Magazine, anonymous. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland

We Demand Manifesto, various authors, Ottawa, 1971; Carl Wittman, print from digital scan of The Gay Manifesto, published by Red Butterfly cell of the Gay Liberation Front, 1970. Photo: Paul Litherland

Jade Yumang, currently based in Gaa-zhigaagwanzhikaag/Chicago, is a visual artist whose work primarily focuses on the concept of queer form—thinking about queer as a “verb rather than a quality.” Yumang has recently started working with back issues of Drum, a monthly homophile magazine founded and edited by Clark Polak in 1964 in Philadelphia. It ran until 1969 when Polak was arrested for “selling and distributing curiosa,” a charge that generally implies the sale of pornography. Drum presented a number of items of interest to gay men ranging from news stories, literature and semi-nude images. As Yumang claimed, “the overall tone was radical at that time as it pushed for celebrating differences and reclaiming pejorative terms … Polak’s goal was to parallel the gay movement to the sexual liberation movement and to not pander to the mainstream.” Drum didn’t attempt to reach a wider audience—it was by gay men for gay men and included gay-specific language that worked to intentionally exclude certain readers. This approach was not always appreciated by the wider gay community, many of whom were trying to champion the “normalcy” of gayness. From their research on Drum, specifically the final issue, which came out in the winter of 1969, Yumang has been creating soft sculptures in order to trace “a moment of resistance that was not supported within the queer movement, which at that time was strident for one voice of respectability and sameness.” This work is about the relationship between obscenity, love, bliss and scandal. Highlighting that most people don’t really understand what happened in 1969, and in the events that lead up to the so-called decriminalization of homosexuality, Yumang’s work celebrates a counter-culture within a counter-culture. At a time when gay communities were attempting to highlight and forefront their connection to heteronormative, dominant culture, Drum celebrated the differences within queerness.

Hazel Meyer and Tobaron Waxman are both artists based in Tkaranto/Toronto. Meyer is an interdisciplinary artist whose work is installation- and performance-based, and involves pre-made and bespoke artifacts, including tools, props and sculptures, and archival research, often in collaboration with her partner, Cait McKinney. Where McKinney’s background is communications and culture, Meyer is interested in the materiality of the archive, a subject that came up for all the subjects. For Where Once Stood a Bandstand for Cruising & Shelter (2017), which Meyer developed using archival material and oral histories from the City of Toronto Archives and The ArQuives/CLGA (in particular, the Foolscap Oral History Projects), she reflected on material traces—the sweat stains on T-shirts, the smell still lingering and the wind holes in the marching banners. This and other projects think through what gets included in an official archive and what gets left out. For Meyer, archival research is an investment.

A sanctioned archive is safer, but it is often as incomplete as the one in the family home. It does not create a full-spectrum report of trans histories.

Waxman can be described as “a visual artist who sings.” They are also the Trans Archive Assistant at The ArQuives/CLGA, part of a collaborative team creating the Trans Archive at the largest independent LGBTQ2 archive in the world. As an archive keeper, Waxman is devoted to what they call “radical hospitality.” The archives themselves are a sacred holding of history—without The ArQuives, who is remembering these histories? As an older trans artist and curator, Waxman recalls a time when a trans man and his wife in the Toronto suburbs were maintaining a trans archive, at a moment when there, as they state, “were fewer visible trans people around,” but it was destroyed by mould following a flood in the couple’s basement. A sanctioned archive is safer, but it is often as incomplete as the one in the family home. It does not create a full-spectrum report of trans histories. This is why Waxman has prioritized working with living subjects around the oral transmission of these varied narratives. The ArQuives are located in a former residential building, and the homey environment evokes a sense of hospitality and safeness for folks who are considering leaving their material to the archive. There is also the promise of activation: The ArQuives are open to the general public and host regular artist residencies to allow artists to interact with the collection. Creating space for intergenerational transmission allows Waxman and the wider community to maintain their own archive as a strategy of resistance against erasure.

Ross’s exhibition challenged the erasure of both individual histories and national ones. Utilizing funds meant to celebrate the Canadian government’s role in the legalization of same-sex activity—think Pride parades, commemorative coins, positive photo-ops or (Justin) Trudeau’s promise of a posthumous pardon for Everett Klippert, the last person to be jailed for the crime of homosexuality in Canada—Ross redirects the official conversation to highlight the work of activists who disrupt normative positions and queer the narrative.

When governments memorialize an event their intention is generally not to call attention to their failures, but rather to highlight their positive role in a situation. Same-sex sexual activity has been lawful in Canada only since June 27, 1969, when the Criminal Law Amendment Act (also known as Bill C-150) came into force upon royal assent. In Ross’s own words, this means that “‘the decriminalization of homosexuality’ as the government puts it, and, finally, later this year, ‘the partial decriminalization of homosexuality’ after enough of us made a stink, was not really a Criminal Code update dealing with the legality of homosexuality but rather one that sought to control ‘a sovereign bodily exercise of pleasure through the anus.’” The continued patrolling of gay men and cruising culture demonstrates the continued ways in which the Canadian government has yet to remove themselves from the bedrooms of the nation.

Activist-artist David Widgington, along with Meyer and members of Cruise Control, an activist group aimed at raising awareness about the policing of gay cruising sites, contributed banners to the exhibition, some of which were walked to the Mordecai Richler memorial gazebo in Mount Royal Park. Originally built in 1928, the gazebo sits surrounded by land that was razed under Mayor Drapeau in the 1950s to prevent acts of public sex in the park. During the action, the structure was renamed the Mordecai Richler Memorial Cruising Bandstand and involved community education sessions “on the struggle to keep police from assaulting queer people having sex in our historical cruising parks.”

Alongside the contemporary banners activated by this performative action, the gallery displayed a number of archival banners from the various collections Ross visited in his research, since “for legal reasons,” as well as conservation concerns, “we couldn’t bring the archival banners [outside].” Ross adds that “archives are like zoos. It can be hard to see these politically potent, frankly, numinous tools of political agency, stored rolled up and forgotten about. At some of the archives I visited for the curation of this project, the banners were de-prioritized in the cataloguing process, even though they make up a significant part of the collections.” The erasure from the cataloguing process brings up the question of the accessibility of archives and the public versus private nature of these spaces.

Overall, “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” was an archival exhibition about 1969, about public and private spaces, about policing gayness, about the partial decriminalization of sodomy. The subtitle “porter temoignage” (or in English, “bearing witness”) pairs with the second part, “our vanishing,” to place “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” as a counter narrative alongside the larger history of 1969. By asking what’s missing, and by engaging not just artists and archives but also activist groups, Ross creates a loop between the origin of the 1969 decision and the current push for body sovereignty, visibility and a recognition of difference in queer communities. In the same way that Drum pushed against the dominant stream in gay culture that prioritized domesticity and privacy, “69 Positions: Porter Témoignage / Our Vanishing” honours folks who, in the past as well as today, fight to make possible queer sexuality visible in the public sphere.

projets hybris, Nous rêvions à des colères magnifiques, 2016-2018. Prop from the production Youngnesse, mixed media on cardboard and broomsticks. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland

projets hybris, Nous rêvions à des colères magnifiques, 2016-2018. Prop from the production Youngnesse, mixed media on cardboard and broomsticks. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland

The continued patrolling of gay men and cruising culture demonstrates the continued ways in which the Canadian government has yet to remove themselves from the bedrooms of the nation.

David Widgington, We'll Have Our Cock and Eat it Too 2019. Paint on fabric, bamboo. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland

David Widgington, We'll Have Our Cock and Eat it Too 2019. Paint on fabric, bamboo. Installation view of "69 Positions: Porter témoignage | Our Vanishing," exhibition at Montreal, arts interculturels. Photo: Paul Litherland