“My sense is that it is much improved now, but what I describe was an endemic condition for many years for artists of difference in Canada.”

AF: I want to pick up on this oscillation from the margin to the centre and back again, especially in your invocation of Trinh T. Minh-ha and how power relations are always negotiated. Where do you see your own agency or responsibility within those power dynamics with institutions such as the art world and the academy? I recently started a PhD that has very little to do with curating or art history, and I haven’t felt this inspired to learn and research in years. I would be curious to hear your perspective on what it is about these two environments—the art world and the academic world—that conjures such simultaneous discomfort and suitability for you. You have written extensively on both, and accomplished a fair bit in either stream. Would it be fair to say that a certain level of discomfort has been fruitful to your thinking and making? In other words, what does knowing and feeling and owning one’s own discomfort do for your practice?

KL: My late friend, the artist Chen Zhen, used to say that the completeness of the world includes its incompleteness. It is a very Buddhist perspective. Maybe I haven’t gotten to the point that Chen reached, as I am still striving for wholeness and my sense of wholeness requires the world to first be whole. I don’t know how Chen was able to say what he said to me so convincingly, for I see non-identity everywhere. I experience dissonance almost all the time, whether I am sitting on a bus or at home in front of my computer screen. I am thankful to my wife and children for I would not know where I would be without them. Without them I would go mad—I mean truly mad. Whenever I am on my own for any extended period, I feel a strong sense of having to fend for myself, in the most existential terms, even when I have the means to take care of my basic comforts such as a good hotel room or food for the night. Under such conditions, I have learned to travel always with multiple projects in progress.

AF: This is a very honest answer because it is incomplete and opens more questions and possibilities of how to be in the world. You may be closer than you think to wholeness. I have often wondered though if I would ever know what wholeness actually felt like. There is a moment in your 2008 essay “To Say or Not To Say” where it’s the mid-1980s and you have an opening for a solo show in New York. Your grandmother, who doesn’t speak a word of English, shows up and asks, incredulously and repeatedly in Cantonese, “Who are all these people?” Your grandmother showed up because she is family, but you write that you felt completely exposed of your private self, which included your family, class background and race, as opposed to your public self, which is the artist self. I found myself returning to this passage of self-bifurcation. I’m still stuck on it, particularly on the seemingly unconscious tactic to hide one’s class and race, which realms like art and academia expect us to internalize and hold. For myself, I think this splintered sense of self is a by-product of growing up across two different cultures that are epistemologically opposite from one another. I never feel fully seen or heard, yet alone understood by either side. Is this just the challenge of being alive?

KL: I have never hidden where I am from. Rather, I have found it difficult to negotiate one self to another self, especially in an unmediated sense. A self is always a representation of the self, at least regarding public projection. When my grandmother showed up at a very public art world event, it was shocking to me—there was no transition time to switch from art-world me to non-art-world me. It was an experience that broke down the symbolic order. I could only ignore all the gallery attendees dressed in black and respond with affection to my grandmother. The issue is not that I have felt inadequately seen or heard. I think it is more nefarious than that. I have felt a need from those with greater power to put me in my place because I did not follow the “rules.” My early years as an artist in Canada were all about learning rules on what is proper and not proper to art. I sensed a social ecology that was in place that I had to navigate but did not understand. And when I did start to understand it, I was unsympathetic to why this social ecology had to be heeded. As such, there are many instances when I felt I represented someone to be taught their place. We don’t have the space here for me to elaborate with examples but the problem of not being seen or heard was not the problem; it was more that I felt disallowed from being seen or heard. My sense is that it is much improved now, but what I describe was an endemic condition for many years for artists of difference in Canada.

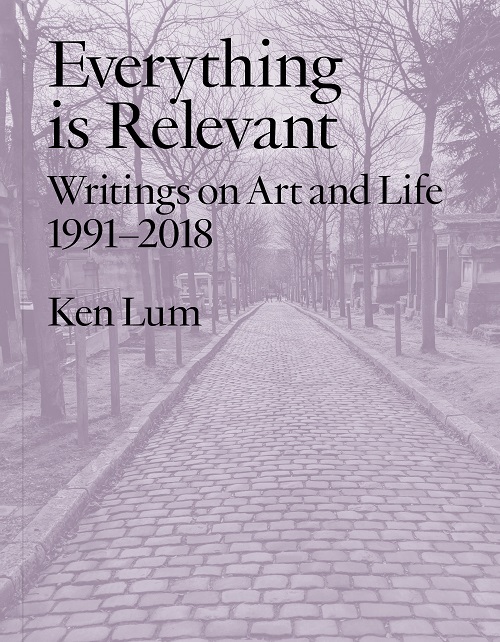

Cover of Ken Lum's Everything is Relevant to be released January 2020 from Concordia University Press

Cover of Ken Lum's Everything is Relevant to be released January 2020 from Concordia University Press