As a part of a performance/installation in San José, Costa Rica, in 2008, Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa slept with a large bunch of bananas for two weeks, letting them ripen through his bodily embrace. His intention was to question whether “the Central American psyche has been affected by its interminable economic dependence on the exportation of bananas.” The project was called “Para ti el banano madura al peso de tu dulce amor,” or “For You the Banana Ripens to the Weight of Your Sweet Love.” For “A Brief History of Architecture in Guatemala,” first performed in 2010, a set of dancers wear the likenesses of Guatemalan buildings and ancient Mayan temples made from white corrugated plastic. To carnivalesque music, they move their bodies to and fro, eventually knocking into each other with more and more force until the buildings break apart and the performers are left bare.

Ramírez-Figueroa has been making different kinds of work since his teenage years in Vancouver, where as a child he immigrated with his family to escape the Guatemalan civil war. Ever since, Ramírez-Figueroa has been working through personal and political issues in sculpture, installation, performance and video. Art led him to Emily Carr University of Art + Design, the Art institute of Chicago, and the Jan Van Eyck Academie in the Netherlands.

On the occasion of his participation in several upcoming Canadian exhibitions, I talked to Ramírez-Figueroa about his thoughts on performance and what it’s like being an artist in Canada.

YL: You work in all these different forms–sculpture, installation, performance—that in some ways your work seems to be ideas driven: whatever you’re interested in will come out however it needs to come out. Your practice seems to be so interdisciplinary, how would you describe it?

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa: I think it’s exactly what you said. I came about in a generation where nobody pressured me to pick one medium, and for that I feel very lucky. Of course, there were some people that said, “Oh, you’re a performance artist,” or “Oh, you’re a painter.” But in general the people who said [those things] weren’t people I perceived as having any authority. It never even passed my mind to stick to one medium!

I did feel that even though I was making many things in many mediums, I didn’t develop a voice in every medium at the same time. Since my late teens and early 20s I’ve been making sound art and sculpture, but I don’t feel like I started making sound artworks or sculptures that were really good until way later.

YL: So, once you figure out how you want to work with it, you find a distinct voice in each medium?

NRF: Whereas with performance, I’ve been exhibiting and doing performance since my teens. I’m 40 now, [so] it’s been 20 some years since [I started]. I’ve had to rediscover what I wanted to say in performance art because at some point I felt a bit bored with it, or not bored—a bit disappointed with it.

When I started doing performance in my late teens it was an opportunity to say something particular, and to have a body that looked like mine out there in the world. But then in my mid-20s I made this performance at the Vancouver Art Gallery and people were really rude—I could hear them commenting on the imperfections of my body. I also got this horrible article [written about me] in a literary magazine here in Vancouver, and it just talked about my fat and how maybe the clothing did not fit that well. That sort of killed my idea that performance was a way to connect. Certainly most performances I see [now] are kind of about fashion, and about attitude and about things I don’t really think about.

YL: What are your ideals of performance or what do you think performance should be able to do?

NRF: I participated in this panel again at the Vancouver Art Gallery with Dana Claxton and Skeena Reece [as a part of the Gifts of Fringe series]. I was talking with people who were my colleagues and my teachers when I lived there, and a younger performance artist named Jeneen Frei Njootli. She ended the conversation by saying performance is a way for her to speak, particularly as a young Indigenous Canadian person. I was really moved—for me, when I [had] started making performance in my my teens or in my 20s, it was something very important to me.

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Mimesis of Mimesis, 2016. Performance for video. Photo: Florian Braakman.

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Mimesis of Mimesis, 2016. Performance for video. Photo: Florian Braakman.

YL: Although you’ve worked with mentors like Rebecca Belmore, you’ve talked about people saying things to you that weren’t necessarily encouraging. How have you found people to guide you in ways that were beneficial?

NRF: I think they found me. Even though I went to art school for many years, I think a lot of my knowledge came, obviously, like many people, from my peers—at Emily Carr, or the [Chicago] Art Institute, or Jan Van Eyck, and then of course people like Rebecca, or others in Guatemala. There are people who have been able to educate me. I sometimes don’t really know what I did in grad school, I mean I liked it but I don’t know what I did those first years at Emily Carr!

YL: Could you talk about it; what did you do those first years? Did it seem like you were learning, like they were teaching you how to be an artist?

NRF: Well sort of, in a way. I think with Emily Carr, at least the education I had, they were looking a lot at what was happening in London and New York, and I thought that was very colonial. So I liked when I went to Chicago because Chicago has a real history of trying to ignore what’s happening in New York and LA. And then it gave me that gift of trying to recenter my own work, to break this colonial education that I felt I got. But maybe I’m wrong–

YL: Well you can’t be wrong, that’s your experience!

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Print of Sleep, 2016. Performance.

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Print of Sleep, 2016. Performance.

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Print of Sleep, 2016. Performance.

Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa, Print of Sleep, 2016. Performance.

YL: You talked about wanting to move away from some of the themes that have been a part of your work for a long time. You deal with trauma and the Guatemalan civil war, or address those legacies through your own personal family history. With some of the stuff that’s been going on with the new president in the United States, especially a heightened fear about migrants and attention to borders, have you felt a renewed urgency to deal with these topics?

NRF: Yeah, I mean sometimes I think I never will [stop making work about] the Guatemalan civil war because I did live it as a child and my family was very involved. That’s even why I came to Canada as a refugee. But right now with our new president in Guatemala really attacking women’s rights , the rights of queer people—like trying to ban gay pride this year because its goes against “common values”—then I feel like there’s more urgency to be more present.

I talked about the whole migrant thing in an interview with Betty Marin. She’s a daughter of Mexican migrants, and of course there’s a lot of Guatemalan migrants and people who don’t have papers. It’s such a harsh and epic topic. In Guatemala I have known people—young people—who have gone on this journey, and it’s just, it’s beyond me, I don’t know. When I was a refugee I was very privileged in a sense because many countries offered us asylum, so a lot of borders were open to us. I don’t know what to think about this [current situation]. I mean I know it sounds very bourgeois but I can’t imagine risking your life to go to the US.

YL: Could you talk about your relationship to being here in Canada. Have you always found a home here, whether as a refugee, or in the arts?

NRF: Do you remember? They passed a law, or they tried to pass this law. It said people who come as refugees could have their status taken away if they are found to have committed a crime, even if they are Canadian. I think it was passed—I should check, it might be still in place, or maybe we all ignore it. With those things, even it it wasn’t passed, it makes you feel like, “Oh, am I really a Canadian?”

You know, another thing I think about is that when I used to live here, and I have a Canadian passport, people always took me as a Guatemalan artist even if I asked them not to. People are still doing that automatically, I have to correct them. I felt like “Oh whatever, you know, I’m not gonna try anymore: I’m just not gonna put you on my cv.”

YL: Is it that people want to put you in a box?

NRF: I think that sometimes it happens when people try to make a cultural narrative, especially a national or a local one. I guess the Latin American experience just doesn’t resonate here.

YL: What do you mean by that?

NRF: Latinos in Canada are just not a subject or an issue that people talk about. I guess we’re not that many Guatemalans. Here in Vancouver it would be [another demographic] that would be more relevant or something . I mean, I don’t know: is it the same for you being Black in Canada?

YL: Yeah, well I wrote a whole MA thesis on this. Because many different communities exist here. There are even many different Latino communities. The arguments I made around blackness in Canada had to do with being excluded from national history. With the exception of ideas of multiculturalism, which always, as you said, place us as an add-on.

NRF: Yeah, I mean most of the group shows I ever had were multicultural shows, and I’m like, “Yeah, whatever.”

YL: Yeah, and that sort of doubles down on a binary that, yes, acknowledges Canada as a settler colonial nation, but only in regards to a relationship between Indigenous folks and Europeans, and that all the rest of us are in this floating middle ground. Immigrants, or subject to the benevolence of the Canadian state.

NRF: Yeah, where is my mosaic?

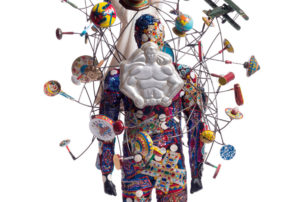

Ramírez-Figueroa’s exhibition “Corazón del espantapájaros (Heart of the Scarecrow)” will be at the Audain Gallery January 17 to March 9, 2019. PuSh International Performing Arts Festival will co-present a series of Ramírez-Figueroa’s performances from January 16 to January 19.

Ramírez-Figueroa is part of the group show “How to Breathe Forever” at ONSITE gallery in Toronto. On Wednesday, February 13, Ramírez-Figueroa will lead Séance with Extinct Species of Birds. Limited availability; registration required.

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, Corazón del espantapájaros (Heart of the Scarecrow), 2016. © Ilana Bar/ Estúdio Garagem/ Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, Corazón del espantapájaros (Heart of the Scarecrow), 2016. © Ilana Bar/ Estúdio Garagem/ Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.