Dana Claxton: I’ve been thinking about what the question of pleasure means when it comes to making art: What kind of enjoyment or satisfaction comes from making art? How do we derive pleasure from these experiences?

Skeena Reece: Last year, when I had a show at Plug In ICA in Winnipeg, I invited Julie Nagam, an Indigenous artist and curator, to do a performance with me. I wanted my public—and I was hoping there would be a lot of Indigenous people there—to feel a sense of pleasure. My work is politicized and for some it’s difficult to be in. Often, the people I perform for are not Indigenous, and sometimes I’m implicating them as perpetuating violence against us, whether inadvertently or overtly. Winnipeg has a sordid history of violence and to this day it’s one of the worst places in Canada for a Native child to be, so I wanted to help my people feel well. I found out that Julie was a figure skater and I thought wouldn’t it be nice to take a moment, to take three minutes out of your life, to just watch someone gracefully move around in the white cube? The absurdity of it all, the inner joke, for me, was having people looking very seriously at this Indigenous figure skate —on rollerblades, in the gallery, fully dressed as a skater would be. I thought they weren’t getting the joke, but when I looked back at the photos, I was in tears laughing at one of the people watching: he was an Indigenous man, and he was trying so hard to stifle his laugh. In every frame you could see he was just biting the inside of his cheek, trying not to disturb everybody. That was the whole point: I just wanted you to be out of your politic for a second, just to have some rest. The fact that he got it, even if he was just one person, gave me as an artist so much pleasure.

DC: I think sometimes pleasure gets denied. We’re in this post-capitalist, neoliberal political moment and through this chaos there is, I think, a certain denial that we should experience pleasure. There are theoretical ideas around this—I think it was Adorno who said there can be no art after the Holocaust—but I’m thinking more about Indigenous subjugation and how we still, of course, have Indigenous humour. I think it’s important that our communities have pleasure, despite oppression.

SR: Oh, it’s tantamount to our survival. So many of our people are steeped in this reptilian part of the brain, where we’re simply surviving, even to just be walking through the streets. I wonder what non-Native people think of us when they’re experiencing pleasure. Are they allowed to feel happy around us? Is there some sort of dichotomy, or a rift they’re detecting? I also wonder how that translates to seeing our art. Is it the same sense of, “I cannot share in what you believe is pleasurable, because we are not the same”? I wonder, too, if there are many tiers of access, and how access plays into pleasure. I mean if you’ve never had access to Native art, or language, or our nuances, then maybe you can’t take part in feeling pleasure when you see our work, or experience it.

DC: I like this idea of a tiered system of pleasure. It’s intriguing to think about those “missed pleasures” when you don’t know the inside of a culture.

SR: Yes, well it kind of reminds me of portraiture. And how people feel more prone to gazing upon a subject when that subject is the subject of their gaze. That people take more pleasure in gazing at something, as opposed to being gazed upon. Right?

DC: So, when the viewer (and I’m thinking of the non-Indigenous viewer) is looking at the image made by an Indigenous person and—for lack of knowledge, or understanding, or because of ignorance—there is a lack. Are [they] denied pleasure, simply because of their own lack of knowledge?

SR: I think that [the denial of pleasure] translates to other things in the world, like what about BDSM? What gives people pleasure is arbitrary, or not arbitrary but individual,but there’s always this underlying thing that is often associated with some sort of pain or detachment.

DC: That’s making me think about privilege [and] pleasure— what is pleasure’s attachment to colonialism, and is colonialism sadistic?

SR: Oh it absolutely is. It’s rooted in sadism.

DC: To want to do that kind of harm…

SR: How could [people] continue to do it without some sense of pleasure?

DC: So thinking about colonial, sadistic pleasure, and how that gets intergenerationally lived not only through, quote, the victim, or the receiver of it, but also the perpetrator. Within the context of contemporary art, the viewing public is generally a non-Indigenous crowd, from Western backgrounds and settler communities, so they’re coming from this colonial, sadistic history. They’ve inherited that. They’ve been taught that. It’s part of their visual world. And now they’re coming in to view Indigenous art. That’s a dynamic that has a relationship to power then; there’s this colonial pleasure, colonial sadistic pleasure, related to power when viewing Indigenous art.

SR: But you know why there are so many missing Indigenous women? I think I’m reflective in terms of wanting to add that posed as a question. I mean, so much of who we are as people comes from our upbringing, and who are the leaders in our families? They’re usually women. And so who are the carriers of our knowledge, and who are the carriers of our culture and in turn our art practices? The women of our communities. And so we can’t have this conversation without acknowledging that somebody is taking great pleasure in our disappearance.

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016. Performance. Courtesy Audain Gallery. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016. Performance. Courtesy Audain Gallery. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

DC: The State that polices, the Indian Act, the disallowing and regulating of Indigenous women—it’s so concrete, historical and embedded. It informs by de-matriating, by taking away the matrilineal authority, if you will. By disallowing and disavowing matrilineal knowledge, legally, “we” (the political system) start criminalizing matrilineal knowledge. And that criminalization gets transferred to your children and grandchildren.

SR: I think a lot of [Indigenous artists] are making politicized art because we haven’t even gotten to the point of an equal playing field. Who is allowed to have pleasure? Or who has the time to create images or works of pleasure, or to enjoy the pleasure? You look around at any opening, you don’t see a sea of Native people enjoying the work, or making the work. For me a lot of it ties into the access side, and the privilege side, of art.

DC: When does pleasure become classist? The leisure class can’t be the only ones who get to have pleasure! For, quote, the poor, or the marginalized or the unemployed or the proletariat or people who are removed from the leisure class—how is their pleasure obtained? Because surely pleasure is not simply allotted.

SR: Pleasure is subjective, and so it’s kind of hard to pin down. This conversation has prompted me to think: Do I make art to pleasure others? And is that wrong? And am I simply stroking the ego of the viewer with my work? Am I preaching to the choir, so to speak, by making politicized works for my own audience, my like-minded people, or am I getting pleasure out of challenging others? And then what pleasure do I get from other Indigenous artists, or other artists? I would have to say, it helps me to grow. For me it’s tied to growth, and learning.

DC: And sharing, and giving…I think pleasure also resides within the realm of the gift.

SR: You love giving—and that’s a Sioux thing isn’t it?

DC: The Sioux generosity, one of our virtues. But even thinking about art, we’re making art that’s not for ourselves. You have this image that has to come out. So you create it. And then it keeps living, then it lives again when people view it, it lives in the gallery, and then it lives with their experience, and then it lives when they talk about it. And it lives when art circulates. So that giving of pleasure is extended beyond just one viewer looking at the work.

SR: This reminds me of my dad. He would usually make [a mask] in about five weeks and then he would hit the road for a sale. I used to think, how sad that he would make something so close to him, and beautiful and unique and painstaking, and simply give it away for a small monetary gain. I thought that there must be so much pain involved with letting go of something he took so much pleasure in. But he said to me, “I don’t have any emotional attachment to this object.” The pleasure is the relationship that he has with the object. It was his experience carving the wood, touching the wood, making it come to life. That was the value: the experience with the object. I think that absolutely informed my art practice. I want to show people that the value is not in the object, but in the value of the people. [And] to ask the viewer to please not value the objects—because we are still here.

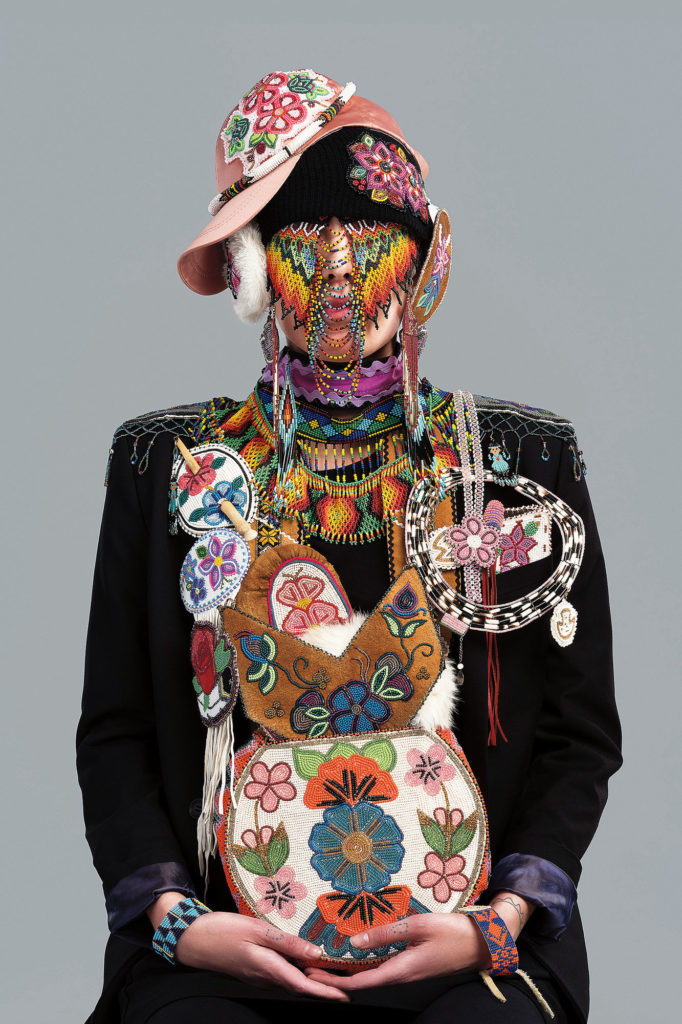

Dana Claxton, Headdress–Jeneen, 2018. LED firebox with transmounted chromogenic transparency. Collection Cathy Zuo. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery.

Dana Claxton, Headdress–Jeneen, 2018. LED firebox with transmounted chromogenic transparency. Collection Cathy Zuo. Courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery.