Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, Barcelona-based artist Carlos Bunga developed a site-responsive installation across the first and second floors of MOCA Toronto’s industrial space. His primary materials, like some of his previous work, were cardboard, household paint and adhesive tape—materials reminiscent of makeshift homes and unstable structures.

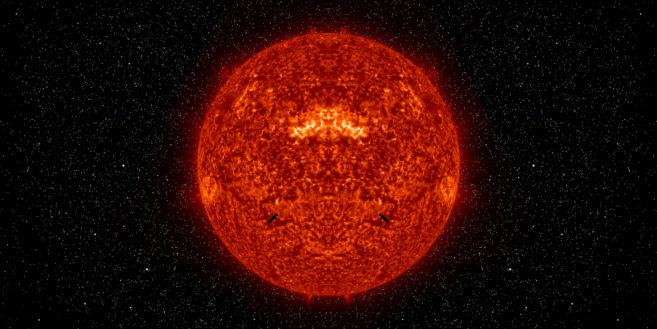

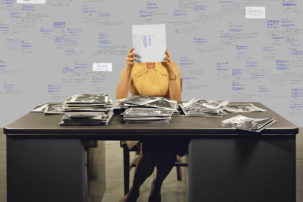

Bunga’s first-floor installation, Procession (2020), a monumental-sized work consisting of cardboard beams and pillars, was painted haphazardly and unevenly, evoking an impression of deterioration usually associated with long-term exposure to the elements. The second-floor piece, Occupy (2020), a series of cardboard boxes spanning outward rather than upward, encouraged physical engagement from spectators. Visitors were invited to walk through the temporary landscape, sparking new spatial relations between the audience and the work.

“He started to work more horizontally when he first went to the desert in Tucson,” said MOCA adjunct curator Rui Mateus Amaral, who commissioned the work. “He became really interested in how he would just drive for hours without seeing a curve or a right angle. It was just infinite.”

But Bunga’s installation, and his attention to the idea of “the ruin” and public space, takes on a special resonance in the era of COVID-19. In an article for the New York Times, architecture critic Michael Kimmelman describes the pictures of empty public spaces as evocative of “the romance of ruins.” Whether it’s Times Square in New York, the Piazza San Marco in Venice or the Grand Mosque in Mecca, the stark desolateness of spaces normally characterized by heavy foot traffic is unsettling. The enormity of these now barren landmarks suggests a past life of human activity and civic engagement, the sense of ruins located in the simultaneous emptiness and vastness of public space, eliciting a sense of loss.

Bunga’s installation, and the way it plays with the distinctions between monumentality and deterioration, speaks to these meditations on mourning. Indeed, the intermingling of grandeur and decay (as exhibited in Procession) confers a sense of transience onto the type of built forms we usually associate with permanence and protection.

At the same time, both installations necessitate interaction from the spectator. Without engagement from the public, these structures are also ruins. Their continued presence at MOCA, behind its locked doors, evokes an imagined desolateness akin to that of these newly emptied public spaces.

The following interview was conducted in early February, before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, and was followed up with questions by email in recent weeks. Both interviews have been edited and condensed to reflect on the new realities posed by the virus.

Carlos Bunga, Procession, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

Carlos Bunga, Procession, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

Sarah Ratzlaff: To start off, could you describe the process you underwent in creating the two installations for MOCA? I know they are site-responsive, so I’m wondering what about the space inspired you.

Carlos Bunga: In October, I came to Toronto for the first time, and I visited the museum and the neighbourhood, and that was very impressive for me. I’ve worked in many museums and many countries, but this museum is very singular, unique, particular. That also means that it is very difficult to make something in this building. It is not the typical white cube. It has a lot of energy, with columns that are incredibly present in the space. In my first visit, I tried to feel the buildings, understand the neighbourhood, talk with the other people who work and live here.

My process is different, compared to working in a studio. In the privacy of your studio, it is up to you when your work is ready and what you want to show. In my process, the space I work in is both my studio and the site of exhibition. In my case, you don’t send the art piece. You send the artist. When I work in a given space, I consider it to be a kind of informal performance, because people often don’t know what I’m doing or what I’m up to, especially because I’m working with cardboard in these kinds of strange ways. It allows for this informality that I think is very nice.

SR: How does your current practice connect to your training as a painter?

CB: It’s true that I started as a painter, and I still consider myself one. When I look at a given space that I’m supposed to work in, I see it as an empty canvas, and on an empty canvas you have to decide where you will put the first colour. You have the frame of the canvas, and that is the limitation, just as the frame of the building is a kind of limitation that you have to work within. I consider the way I work in a given space to be a painting process. My work is always something in between sculpture, architecture and painting.

I also believe that the piece only starts when the people come inside. When we start to walk around the work, something begins to happen. In Occupy, with the cardboard boxes, I think it’s important to take your shoes off when you step into the piece. I believe it signals a kind of ritualistic feeling.

SR: It’s also a rather vulnerable act, taking your shoes off. It’s kind of reminiscent of entering a home.

CB: Totally. That connects with the furniture that I found around Toronto and brought into the exhibition space. I do think that the concept of “home” in my work is very important. MOCA is a very industrial space, but somehow, at the same time, you feel at home, which is a very strange feeling.

Carlos Bunga, Occupy, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

Carlos Bunga, Occupy, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

SR: Is there a way in which “A Sudden Beginning” might also speak to the current pandemic and related calls for self-isolation and physical distancing? What are your views about the status of the work now that people cannot enter the gallery?

CB: I developed the work to deal with concepts such as fragility, temporality, memory and fragmentation. These concepts seem to echo the current moment in which we are living. The contemporary landscape is the urban space with all its contradictions. I think that architecture in cities needs interaction from the public. Without people, urban spaces or houses become ghost towns. However, the obligation to hibernate in our homes, leaving the public spaces empty, has created room for nature to breathe and be reborn again.

SR: Now that there is no one interacting with your installation, is the artwork perhaps waiting to be realized or “activated”?

CB: All the installations I have done in the past have been destroyed and do not exist physically. There is only documentation (photography, video, texts, etc.). They are artifacts from a specific moment. I don’t feel that the work that is currently in the MOCA is finished or closed. There will always be new ways to reinvent the work. The public will continue to be important in activating the piece. The people who have had the opportunity to physically experience the works are privileged. It is a unique experience. But documentation is another way of dealing with the work and maintaining it over time. Today, technologies, digitalization and the internet are creating new public spaces to be explored.

At the same time, the more technology advances with these new digital spaces, the greater our nostalgia will grow. We need to touch the earth, to breath the air, to love, to kiss. What is fundamentally human about us will drive us to seek out those real spaces that exist outside of Plato’s Cave.

SR: Occupy was very low to the ground, which is in contrast to the more vertical Procession, on the first floor. Could you talk a little bit about your experience with ruins, and the kinds of connections or distinctions that may be drawn between ruins and monuments?

CB: Ruins are very important to my work, but this piece on the second floor came into my work because I spent a period of time in the desert in Tucson. I rented a car and travelled to Arizona, the Grand Canyon, New Mexico. The scale of the landscape was very impressive to me, and that kind of interest in the landscape is similar to the works of Minimalist artists. The interest in the scale of the landscape is similar to that kind of tradition.

Carlos Bunga, Procession, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

Carlos Bunga, Procession, 2020. Installed at MOCA Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitez (Madrid) and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

SR: Is that interest in vastness connected to any frustrations you had with the physical and spatial limitations of painting?

CB: Yes, I think my interest in scale and landscape kind of came from my frustration with painting. But at some point I started working in the city, and I started to become fascinated with old buildings, buildings that had collapsed. The collapsed appearance of certain structures started to be very beautiful to me, because I thought that those buildings spoke to themes of memory and time, and I started to see these ruins as beautiful paintings. I started to take some paintings of mine and I hung them on walls around the city. After hanging the paintings up on walls, I felt as if they became invisible.

Not long after this, I started working with very simple materials, like paper and plastics. I tried to make little buildings, and I felt that these buildings were very fragile. You know, paper is fragile, cardboard is fragile, but you can manipulate it. I think cardboard is the way I can talk with many different concepts: it deals with fragility, temporality, mortality, and it’s also a very banal material. I think that the temporality and fragility of the cardboard material reminds us of our own mortality. I call the surface of my work a skin, because it’s organic, very close to nature.

With these materials, I began to play with the concept of ruins more and more. I really think the ruin, which I see as a collection of fragments, is a space for creativity, because I feel that the absence of something forces your brain to contemplate what was there.

SR: It’s amazing that one material can be highly suggestive of so many different mediums.

CB: For me, people’s need to categorize has always been very funny. What do you do after you’ve found all the answers and categorized everything? Where do you go from there? I really think that a certain kind of stimulation happens when we enter spaces where not everything needs to be classified or understood. I love that space between possibility and impossibility, a space where we can ask questions. That’s why the concept of the nomad is very important. For me, the most important part of the nomad isn’t physically travelling from one space to another. Instead, I think the most powerful thing about being nomadic is the capacity you have to travel between these strict classifications. That doesn’t mean I want to collapse these concepts or distinctions. Rather, I want to travel from one concept to another, to travel in the space between these categories.

SR: I’m wondering if your self-described identity as a nomad has changed during these times—has your artistic practice shifted now that you cannot travel to the gallery to complete work?

CB: While my work has taken me to many countries, the most important part of nomadism, for me, is still in thought. In this way, the current context allows me to keep being nomadic.

SR: Have you now started making works in the privacy of your home?

Since the outbreak of the virus, I have taken the opportunity to draw, since I consider drawing to be a reflection of thought. I am trying to make drawings of the projects I carried out in the past, in addition to some drawings relating to the current context. Here, documentation is not only a representation of the real but also an analysis of the process. This process of drawing my installations after they have been created allows for reflection. There are several questions that have led me to develop this “reverse” process. The limitations of real space become free on paper, where gravity does not exist.

We are afraid of getting sick, of dying. Our houses now function as a second skin, a womb that protects us from the outside world, where we feel safe and loved. In these times of hibernation, drawing helps me to reflect. In my house, there are several ideas wandering through my head that will surely be reflected in artworks and objects. In my little room, on my little table, I’m able to reflect upon the world and build ideas that can be put into practice in the future. There is always room for thought.