I’ve known Shaan Syed since 1999, when I first met him through the South Asian Visual Arts Centre in Toronto. But I feel I didn’t know much about who he was as an artist until I saw his degree show at Goldsmiths in London in 2006. Since then, I’ve observed a very specific dedication to painting and to abstraction in his work—more recently with a dizzying push-pull where both up and down seem to occur simultaneously. All of this was seen in Syed’s recent solo exhibition “Maghrib” at Parisian Laundry in Montreal, and more will be on view soon in the group show “A Tapered Teardrop” at Terrace Gallery in London in September.

Swapnaa Tamhane: Let’s start with the exhibition series and space you ran in Bethnal Green, East London, called “Aqbar.” Can you talk about the impetus for this project?

Shaan Syed: Aqbar came about through getting access to a tiny one-car garage typical of council-housing estates in East London. The concept was that each exhibition would be a solo show with one work, with a focus on painting in its various forms. I’d been painting text over the last several years and this got incorporated into the program with me painting each person’s name in the lead-up to their show, which would be posted on social media as the invite. I wanted to create a space that people had to make a commitment to come to, and when they got there, they’d be confronted with having to look at a single painting. In a way, it was a reaction to all that finger-swiping we do now to “look” at art. Sadly, the neighbours took it upon themselves to have it shut down, but I managed to run it for about a year, up to April 2019.

ST: Why was “Aqbar” as a name significant for you?

SS: The name Aqbar had a few references—there’s a short story by Jorge Louis Borges called “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” in which two characters discuss finding an insert in an encyclopedia describing a place called Uqbar that could be spelled in several ways. The inhabitants of this place speak Arabic but they’ve gotten rid of all nouns, only speaking in adjectives, verbs and adverbs. As a result, the culture is a non-materialistic one, but it’s unclear in the story if this place actually exists. Aqbar means “big” or “great” in Arabic, which may have said something about the ambitions I had for the space, but was more of a joke about how small it was. It also connects to my own upbringing—my father tried to raise me as Muslim and taught me to read Arabic phonetically when I was a child so that I could recite the Quran. But he didn’t teach me the meaning of the words. I had this relationship with the language that was only visual and auditory: I had no idea what I was saying, but I could articulate the sounds the script was telling me to make. I grew up as a first-generation Canadian—my mother from England and my father from Pakistan, looking like I am white, with a sister who has a much darker complexion than I do, and lately it’s been making me want to push certain buttons in terms of context and how we see.

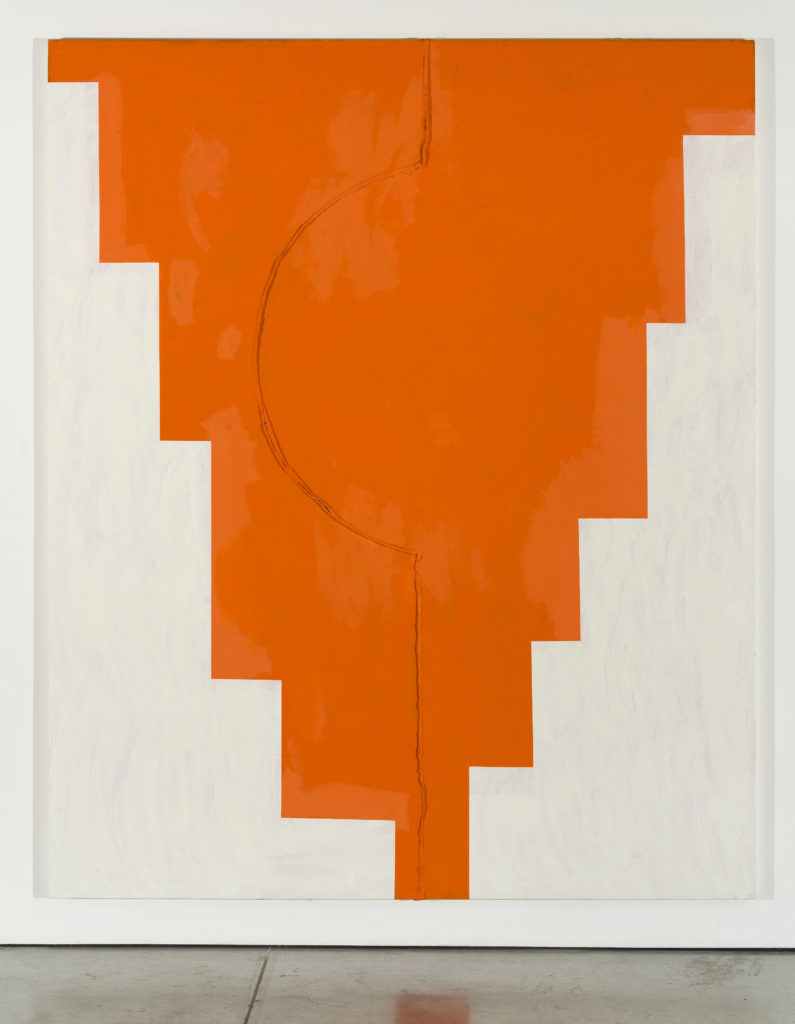

Shaan Syed, Double Minaret (with half sewn disk), 2018. 116.75 X 96 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

Shaan Syed, Double Minaret (with half sewn disk), 2018. 116.75 X 96 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

ST: The surfaces of your paintings are incredibly layered. You encourage this action of “real” looking while creating an experience or sensation of flatness.

SS: Presenting paintings the way I did at Aqbar was a stubborn way of encouraging real looking, which goes all the way back to my grad show at Goldsmiths. Two weeks before the show opened I made this painting that was unlike anything I’d ever done—it was an epiphany of sorts. Up to that point I’d been painting representationally from my own photographs, trying to find ways to obscure the narratives. Richter and Tuymans were big influences. But then I painted this composition that at the time seemed to come out of nowhere—it was very loosely based on an empty concert stage and it made me remember an experience I had when I was a teenager, being so close to a stadium concert stage that I couldn’t see the act. The painting didn’t describe the experience or narrate it, but used it as a way to make a visual and physical experience of looking.

ST: Those stage paintings were also very much about a horizon line. In your new work, recently exhibited at Parisian Laundry in Montreal, is there that same sort of encounter with the horizon line?

SS: I don’t think so. I’m more interested now in creating ways to divide a painting. When you divide a picture, suddenly you have to contend with bringing the two sides back together. There’s a negotiation, tension and reciprocity that has to happen, and it becomes part of the painting process.

ST: Thinking about the stage as a holder for everything that happens on it suggests infinite possibilities and actions, much like how you approach the gesture of painting.

SS: Yes, but the stage is also a construct. It’s two-dimensional: we’re only meant to see the front of the stage, as in a painting. If you imagine a perspective drawing, where all lines converge on a vanishing point, the stage is similar in that if you could trace the audience’s gazes, they would be the lines all leading to the performer. Except a perspective drawing is false—we don’t actually see in one-point perspective. The stage is false as well. Making that first stage painting broke through what I’d been trying to do. It was both abstract and representational, completely flat and on the surface, yet infinitely receding. The contradictions between image, picture and material are what lead me forward, more than having any loyalty toward abstraction or representation.

Shaan Syed, QIBLA 1 (detail), 2018. Oil on sewn canvas. 108 X 84.75 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

Shaan Syed, QIBLA 1 (detail), 2018. Oil on sewn canvas. 108 X 84.75 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

Shaan Syed, Double Minaret (with sewn steps) 2 (detail), 2018. Oil on sewn canvas. 114.5 X 95.5 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

Shaan Syed, Double Minaret (with sewn steps) 2 (detail), 2018. Oil on sewn canvas. 114.5 X 95.5 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

ST: The exhibition title for this new body of work is “Maghrib.” What does “Maghrib” mean to you?

SS: “Maghrib” is the fourth of the five prayers that Muslims are supposed to perform every day. It happens just after sunset and is the only one I was forced to do as a child. Depending on how it’s spelled, “Maghrib” also means “in the west,” as in “the sun sets in…” If it’s spelled “Maghreb,” it refers to the North African countries that arguably make up the Berber Muslim world—Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Algeria and Mauritania. It’s a culture that has an incredibly rich tradition in the applied arts and I’ve been delving into their weaving and painted ceramics over the past while. Maghreb is also the name of a political arts journal that the Moroccan artist Mohammed Melehi used to contribute to in the 1960s. I recently saw an exhibition of his at the Mosaic Rooms in London and found out about his life and work in Morocco. I was fascinated with some of the parallels in terms of the motifs I’ve been using.

ST: The intense pink-orange creates a retinal burn and push-pull. The structure of the step shape reveals itself as a minaret. You go beyond abstraction with an Islamic religious reference and architecture that is designed solely for the action of projecting sound—one would climb the stairs to the minaret for the call to prayer. The structures in your canvases become minarets when two canvases are placed together. What came first, the steps or the minaret?

SS: The desire to divide the canvas was probably the initial drive with the minaret paintings. What the division on the canvas did was set up that push-pull, which brings Hans Hoffman to mind, and his ideas on the visual plays created by colour and form. I was interested in the idea that a push-pull or back and forth also happens between painter and painting, painting and viewer, and surface and motif. I’d been working on this for several years in various ways with my stage paintings, yet I wanted to start using two colours in juxtaposition. This required a system of back and forth: starting a process where one side would be painted, then the other side would be painted in response, then the previous side would have to change and so on, until surfaces became built up and I got to a point where somehow both sides “fit” together with some cohesion or tension. It was like creating a call and response. The stepped diagonal division was the dividing line between the two sides. Somewhere during that process, I came across a picture of the giant spiral staircase of the minaret from the Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq, and it provided the titles, and a thinking anchor.

ST: The Samarra mosque minaret appears flat from a distance.

SS: My experience of that massive minaret is also totally flat—I’ve never been there. It only exists as an image for me.

ST: You’ve spoken before about how you see paintings as signs, which makes me turn to Derrida and his writings on différance, about how language as a series of signs carries traces of both the active and passive voice, and includes the unaccounted for, or traces of absence. Also, of language ultimately being a failure itself. I think of this in how you include your name in your paintings, which on first take is rather strange and falls in line with a masculinist approach to centring name and ego. Why do you include this? What do you want people to discover in your surfaces through the use of language in both English and Arabic?

SS: Where Derrida says language fails, perhaps painting can step in. Painting my name has always been a bit of a joke—perhaps for the reasons you mentioned, but also because of its connection to something outside of that Western tradition. I first started painting it as a way of giving myself a tongue-in-cheek trophy for coming out of the other end of an intense two years where I was dealing with the loss of both my parents and my partner. By painting it I had to look at it. I was doing these very light gouache paintings on paper, in which I was painting my full Islamic birth name—Shaan Tariq Hassan-Syed—in various configurations, accompanied by hard-edge shapes. They were done with a sense of humour and a lightness of touch which was probably because I was open to new possibilities after a dark period. A friend came to the studio, and after seeing the work, introduced me to the Tantra painting tradition which dates back to 14th-century India…

Shaan Syed, “Maghrib” at Parisian Laundry, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Shaan Syed, “Maghrib” at Parisian Laundry, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

ST: Actually Tantrism extends much further back, to 1 CE, and it’s not a “painting” tradition per se; it’s a form of yoga that results in the visual representation of form and sound, or mantras. It’s a science. For my undergraduate thesis I’d written about Tantric “art” and a revival movement called “Neo-Tantric Art” (1950–70s) as a way to counter relationships to American “capital-A” Abstraction. I was, at that time, trying to find how South-Asian artists or those connected to the cultures, histories, traditions and systems of knowledge from South Asia, could stand beside these larger canons that subsume other forms of “abstraction,” and artists arguably continue to do so.

SS: Yes, this is what fascinated me when I found out about them—my own way of looking at them, the cliché of “Oh wow, they look like something the Bauhaus might have done.” That bothered me. Seeing them made me rethink how I was looking at painting and its supposed trajectory, and how I’d wanted to automatically subsume those Tantra paintings into “big-A” abstraction. I started to look at my own background. Growing up in Ottawa in the 1980s, there was usually at least one other “Sean” or “Shawn” or “Shaun” in my class, and as a way of distinguishing me from the other boy with the supposed same name, during attendance I became “Shaan with Two As.” It’s a Muslim name but with the Canadian accent it becomes indistinguishable from the other spellings. At school people asked why my name was spelled like that, and at my weekly Islamic school kids asked me why I had a Christian name. I only discovered that it was being mispronounced my whole life when I moved to the UK in 2004 and heard how the British pronounce it. It became another point of distinction about how things are not necessarily how they are initially read. Painting my name carries with it this history, but is also a way to surreptitiously throw a viewer’s expectations off about a painting. The scratches are only visible when you move closer to the work, which makes me think of Christopher Wool’s painting The Harder You Look the Harder You Look.

Shaan Syed, “Maghrib” at Parisian Laundry. Installation view, Parisian Laundry, 2019. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Shaan Syed, “Maghrib” at Parisian Laundry. Installation view, Parisian Laundry, 2019. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Shaan Syed, Double Minaret (with sewn divide), 2017. Acrylic and linseed oil on sewn raw canvas. 55 X 40 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

Shaan Syed, Qibla 2, 2018. Oil on sewn canvas.107.5 X 84.25 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry. Photo: Guy L'Heureux.

ST: I think you are trying to reveal the contradictions within Abstraction, within painting. The new paintings at Parisian Laundry are so much about a binary of shape and form, but they are also about a binary within culture. We (as people of a diaspora) still have to explain ourselves in terms that are easily understandable to a Western, white audience. This new series, “Maghrib,” extends to a religious reference, albeit in a secular way. These are not just pretty paintings after all. They are a visual struggle. Do you think that everything you are doing and thinking through is comprehended?

SS: The religious reference is there to point to the assumptions made about the work, or any work for that matter. I don’t think what an artist does is ever really fully comprehended, but it’s hopefully looked at and thought about with some seriousness. There are certain judgements I hold the paintings to, or values that I want them to have, at least aesthetically. The drive to make the work comes from personal experiences and perspectives in relation to the various histories or understandings of the medium I’m working in. Challenging my own judgements and aesthetics is part of the project, as is making a good painting—whether the results are understood or appreciated beyond that is something that depends on how much people bring to the act of looking.

ST: What are some exhibitions you have seen of late that you recommend? What are you reading at the moment?

SS: Elizabeth Murray at Camden Arts Centre and Lee Krasner at the Barbican—both excellent exhibitions of great painters on now in London. I’m reading Independent People by Icelandic author Halldór Laxness. I also read an interview with Jonathan Franzen and he challenged anyone to read it without crying. And I’m rereading Isabelle Graw’s new book The Love of Painting.

Shaan Syed, Triple Minaret (with sewn divides), 2017. Acrylic and linseed oil on sewn raw canvas. 86 X 130 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry.

Shaan Syed, Triple Minaret (with sewn divides), 2017. Acrylic and linseed oil on sewn raw canvas. 86 X 130 in. Courtesy Parisian Laundry.