Looking back to that time is like the experience of glimpsing the incipient or dissolving activity at the borders of a room when you pass into it, an image dear to Pierre Bonnard, who painted the formal decadence of domesticity. ‘I’m trying to do what I have never done,’ said the painter of those homely, askew, and yet shimmering compositions, ‘give the impression one has on entering a room: one sees everything and at the same time nothing.’ But where Bonnard’s thresholds are quivering with the dissolution of pattern, always about to be crossed by their spectral, colourfully dressed occupants, much as I, paid domestic companion, had bustled from task to task, a sort of thin, vigorously animated over-painting, what I entered now in my hotel was an annulment of arbitrary conduct and designation. Here I sensed the absence of the previous occupants, all of them strangers, and so featureless, and the absence functioned as a kind of invitation to the tedium of my own interior life, a tedium akin to the boredom or spacious featurelessness of the tidy yet dusty room. Featurelessness was what I craved. This room’s spiritual flatness was a matrix. I did not share Benjamin’s longing for the macabre bourgeois house, with its glossy large-leafed plants, its funereal slipcovers and curtains and carpets, all aired and cleaned and repaired twice annually, with its collections of porcelain, crowds of good family furniture, and scent of wax. It seemed to me that what Benjamin really pined for was the grotesque invisibility of the female work that maintained this mirage, whether purchased or married. I had fled that contract. The places I stayed in were not very clean, and that was fine. They did not pertain to the recognizably female narrative of domesticity I despised. The open question of my future, of what I was to become, felt smooth and shadowy, liberated by these rooms into a textile-like anonymity, patterned with light strokes of pigment and splashes of unaccountable shade.

The cool threshold vibrated with sparseness. Then the hotel’s enclosed scent opened like a grove. I, a girl, exultant, crossed into the room of sentences. This room was suddenly ornate with the written vestiges of silence. No judgment, no need, no contract, no seduction: just the free promiscuity of a disrobed mind.

The room is everything that is the case. The room is everything that is time. It is entirely unexceptional. Each time, the room, this room. I fell upon it unexceptionally. I had been testing the limits exercised by the world upon my girlishness. In the world that deemed me girl, what could I do with pleasure? What could I do for pleasure? I could kiss, I could go to the library, I could study garments. I could explore the possible relationships among these three things.

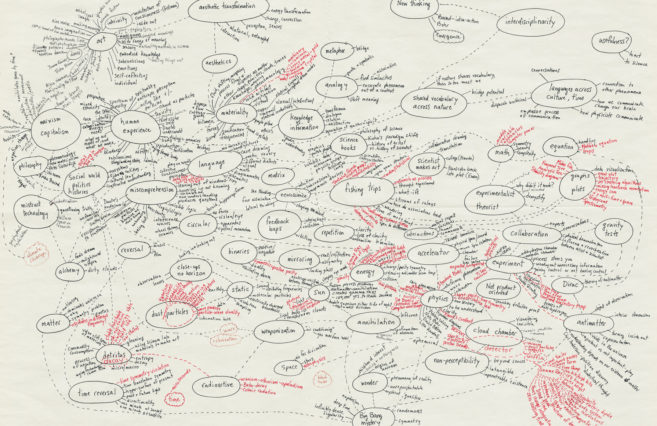

Several of the possible relationships or combinations were more or less interesting, for a while. In the room, though, there was a fourth thing, and a fifth. Entirely outside servitude, I could read and I could think, finally understanding the unexceptional character of these acts. Free of all personal particularity, I read and I thought. I will call it thought, though when I placed it beside the thought of the philosophers, which I unfolded improprietously from within the creased paperbacks, there was no likeness, no identity. I was not bothered. What I felt as thought was at least my own, I believed. The room was not the world, the world that deemed me thing, the world against which I continually bumped and scraped my awkward body as I attempted to move with guessed-at elegance. It was the other world. It is the case that I fell upon this other world of the room accidentally, as falls go. The room demanded no grace. It wanted nothing from me. I fell and then I dallied. The accident of this fall, which is to say, the sudden revelation of the unexceptional character of my soul, when otherwise I had been constrained to sense myself as feminine and so exceptional, and had churlishly accepted the worldly constraint, now introduced me to a more exacting constraint, the constraint of the basic and unexceptional realization of the neutrality, the indifference, the essentially dandiacal aspect of my soul.

The room was crowded at its edges with the written souls of strangers, and this was its particular comfort. I had no responsibilities towards those souls. Neither their comfort nor their pleasure were my domain. They were there because I did not care for them perhaps. I could fetch nothing for them. I did not need them to pay me anything.

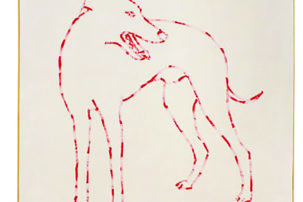

Unaware of the thoroughly comedic nature of the situation, I continued to cross into such rooms, this room, the room of my unexceptional dalliance. I say unaware, but that is not the just word. Comedy was present but latent. The ironic burlesque of the girl reading, the girl lying diagonally across the bed, across the picture plane, this was a genre I had witnessed in the museums of my travels, and also the burlesque of the female reader’s fingers inserted between the pages of the book as if to say here, only here, am I not. These gentle gestures, gestures that were barely actions—the fingers within the book, the pressure of my belly across the too-soft, bowing mattress, the dark fringe of my growing-out hair flopping repeatedly between my gaze and the book, the upward flex of my knees and the rhythmic movement of my bare foot as I turned a page—transformed me into an image of a reader. But far from limiting the possibilities of my inner experience, the little unthought movements made by my body, which from the point of view of an observer would designate me as image within a pictorial tradition, also brought me to the quiet certitude of this body, my odd body, as an image for thinking, an image for my own free use. Here sprung the comedy. Already my body was inside thought. The strangeness of the image, my body, the girl, her inescapable maladroitness—always leaking, bruising, stinking, lusting—originates the infraction that thought must be. For the girl is an infraction in thought. She simply needs to annotate the breach that she is as her reading destroys the purity of philosophy. The idea was hilarious, capacious, like the best burlesque. When in An American in Paris Gene Kelly wakes up in his ship-like room, a tiny space where every furnishing folds or unfolds to become something else, when he enters the elegantly improvised choreography of grooming and beginning his Parisian day, the habitual movements of his compact yet lanky frame unfolding for his own pleasure, like a philosopher’s quotidian thought, but unfolding also with the gentle artifice of the awareness of being perceived, the charm of his dance being his simultaneous refusal of and dalliance with this artifice—were the table, the bed, the basin his perceivers? This was my sensation when I read. It was funny and it was to become contractual. Insofar as I, or rather my body, was an image, an image of the comedy of the girl in thought, I discovered an image to be a composite inner stance or posture. It wasn’t a sign; its meaning was not fixed. The image was synthetic, made, and so mutating and potent. I was not a sign; therefore, I wasn’t a woman either. The image was a fecund entanglement, an infraction that acted within the person, and between persons, and between eras also, a complex of memory, minerals, sensation, and lust. Everything that happened to me then lingered within me, latent, to next spontaneously transform the image of what I’m now saying. The reading girl, the soft action of her fingers in the text, will become philosophy, will become poetry, in a passive but total infiltration.

The above is an excerpt from The Baudelaire Fractal by Lisa Robertson, forthcoming from Coach House Books in January 2020.