A woman walks into a large plywood box lined with astroturf. For 90 minutes, she kicks a ball against the wall, against her knees, against her chest, against her head, against her feet. She plays against herself, and against her context, versus the constraints of the box and its demands. She is on display in a windowfront, clothed only in underwear, her hair cropped close to her head, conveying both severity and vulnerability. Occasionally, she blows a whistle that hangs on a red cord around her neck, calling out her own failure to follow the rules.

This was artist arkadi lavoie lachappelle’s reality for several days this spring, as she activated her installation and performance AAA in the exhibition “World Cup!” at articule in Montreal. lavoie lachappelle used to be a AAA soccer player for Concordia region, and since ending that career she has exhibited and performed as an artist in Cologne, Neuville-sous-Montreuil and Barcelona. But she’d never considered using soccer gestures in her work until she was asked to be in “World Cup!”

“There’s a part of me that was not considering soccer serious enough to be involved with in an art piece,” says lavoie lachappelle in a phone interview. “I had thought about including the skills in actions and performances in the past, but they did not seem enough, aesthetically.”

Then the “World Cup!” exhibition came along, and those worlds of sport and art came together—as well as an opportunity to critique the star system that dominates them both. “This idea of being a star means that you can play alone, without a team,” lavoie lachappelle says. “But this is not true. I think in future, I will explore more about how art and sport, with these ideas of the star player, avoid talking about the team, or the collective.”

lavoie lachappelle’s AAA, and the exhibition it was a part of, are not alone in trying to engage the World Cup within the context of the white cube. As gameplay unfolds in Russia, and spectators cheer (and moan) around the world, some artists and curators are trying to work through how soccer and sport weave through arts and culture.

There is that constant refrain of ‘Keep politics out of sports.’ But sports has always been political.

Amber Berson, curator of “World Cup!” at articule, became interested in the soccer tournament as an art topic when she, as a member of a Toronto anarchist group a few years ago, saw how the championship appealed even to people who self-consciously critiqued nationalism.

“People who were anarchists suddenly got really into this sport about nationhood,” Berson recalls. As a result, in the articule show, “the ideas we wanted to get people talking about were sports, nation and identity.” Berson’s interest in the existence of both fascist and anti-fascist soccer leagues in Montreal and elsewhere also fuelled her research. Other works Berson curated into the show included: Onyeka Igwe’s karaoke unit for soccer songs transformed into pro-Brexit anthems; Sheena Hoszko’s stained-glass renderings of symbols like the maple leaf and fleur de lys; and Null Ace’s video-game version of World Cup soccer, tweaked to play out associated politics.

One artist talk for “World Cup!” involved both speakers and spectators playing a soccer match together in Montreal’s Parc Jeanne-Mance. The game used anarchist rules, with no team-number or age restrictions. Afterwards, “we all sat in a circle and talked about why we did or didn’t play sports,” Berson recalls. “People said that as kids they felt they had to choose between sports and art. Or that they weren’t good at one so they had to be good at the other.” The kind of exchanges that sporting events like the World Cup facilitate are important, says Berson. “Soccer acts as way to have the conversation,” Berson explains. “Sometimes talking with my family about politics is too charged—but if we can all watch this game together, then the conversation becomes less dangerous to them.”

As with other high-level sporting events, the official visuals and branding for the World Cup and its teams are highly prescribed. The official emblem for the event, seen taped up in bar windows and flashed across TV screens throughout Canada and the world this month, has been described by FIFA as a take “on the universally recognizable outline of the World Cup Trophy, while the bold use of red, gold, black and blue in the emblem’s colour palette was inspired by centuries-old techniques seen in world-renowned Russian art dating back to the earliest icon paintings.”

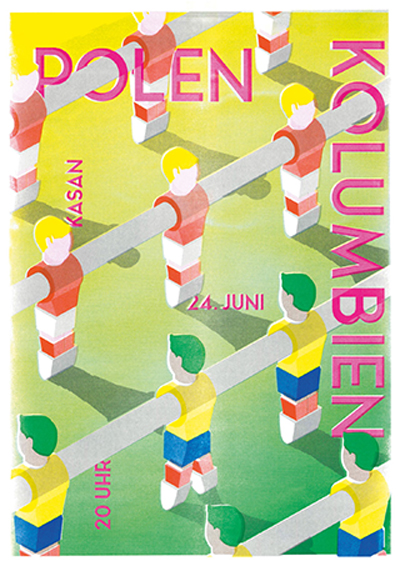

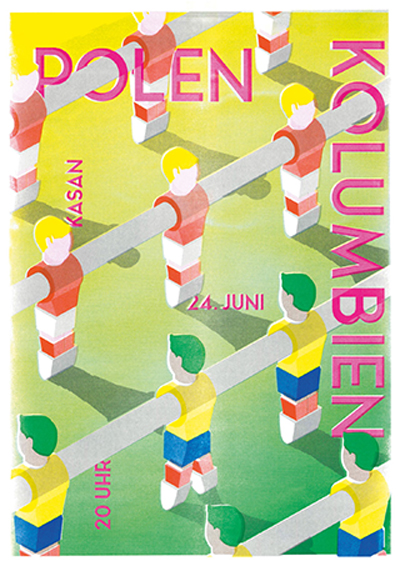

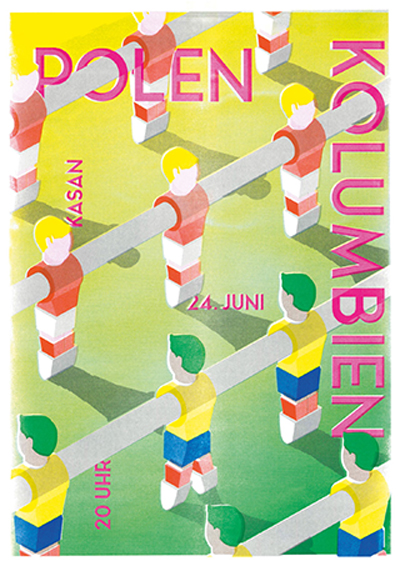

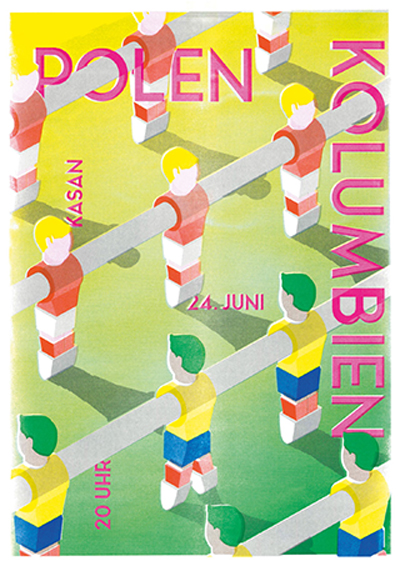

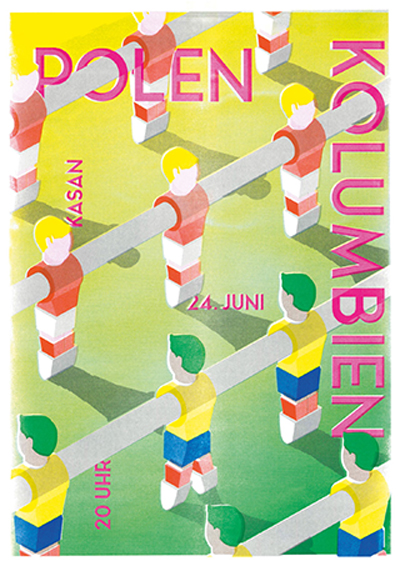

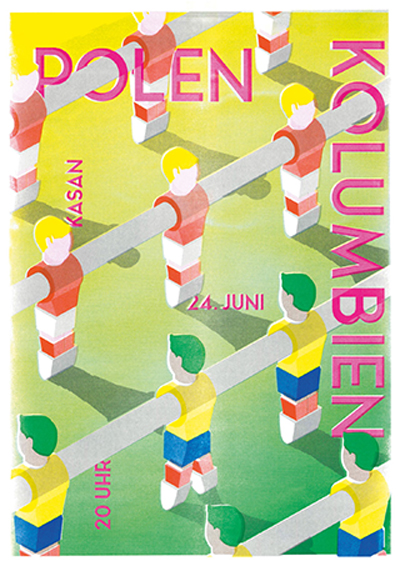

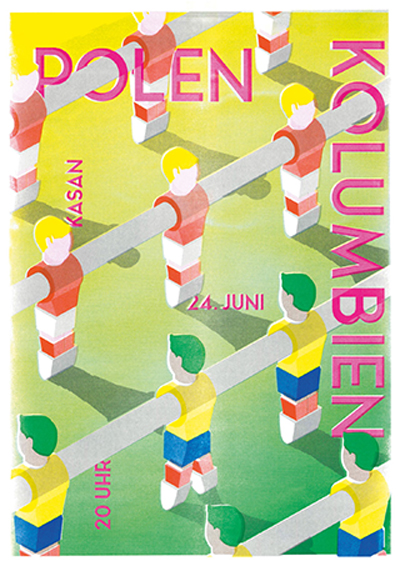

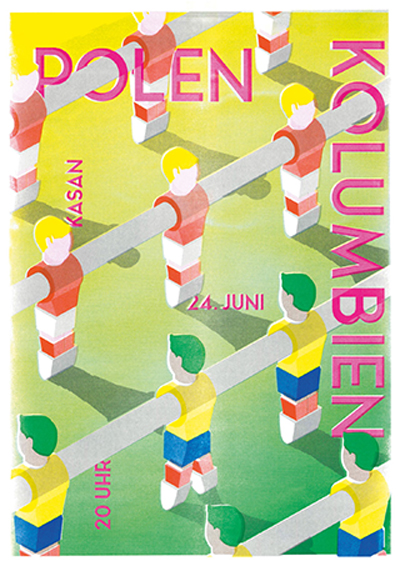

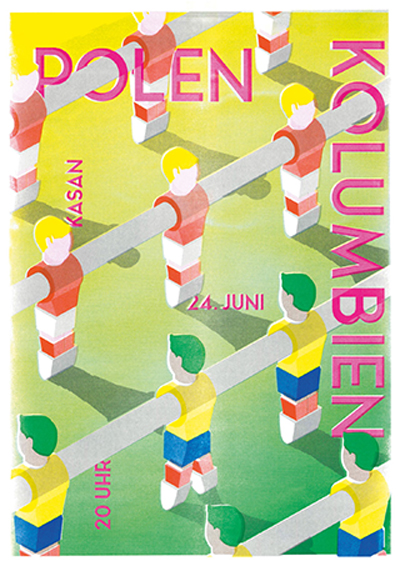

A poster for the Poland vs. Colombia game by Andrea & Raffaela.

A poster by Rodja Galli for Russia vs. Saudia Arabia World Cup matchup.

A poster by Zoran Lucic for the World Cup's Nigeria vs. Argentina match.

An image for the France vs. Australia matchup by Anasatasia Panina.

A poster for the Switzerland vs. Costa Rica match by Al White.

A Belgium vs. Tunisia match poster by Esh Gruppa.

A poster for the Serbia vs. Brazil match by Balthasar Bosshard.

A poster by Anatoly Graschchenko for the France vs. Peru match.

An England vs. Panama match poster by Nini Spagl.

A Morocco vs. Iran match poster by Gabor Palotai.

But a project currently on view at the OCADU Continuing Studies Gallery in Toronto is offering more divergent designs for World Cup matchups. There are stark black and white typographic treatments by Zoran Lucic for Nigeria vs. Argentina and by Anatoly Graschchenko for France vs. Peru; playful emu-versus-chicken visuals for the France vs. Australia matchup by Anasatasia Panina; a foosball motif for Poland vs. Colombia by Andrea & Raffaela; and a politically pointed graphic by Rodja Galli for Russia vs. Saudia Arabia, featuring a woman in a Pussy Riot balaclava as well as a woman in a niqab, each holding different sides of the same soccer ball.

“Forty-eight designers from 18 different countries designed posters for preliminary or group matches,” writes Toronto designer and curator Fritz Park in an email. “What we did was continue with local [Toronto] designers for the following knockout matches, semi-finals and finals…as each match is decided, those designers will have to start working on their individual posters and get it to us so that we can print and display it in the space.”

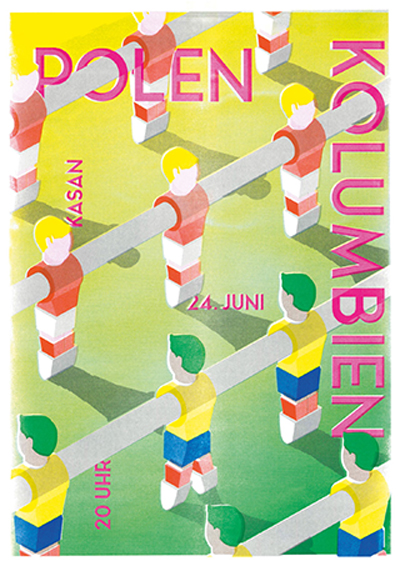

In Toronto, an exhibition of alternative World Cup posters at OCADU offers a soccer ball to sign in place of a guestbook.

In Toronto, an exhibition of alternative World Cup posters at OCADU offers a soccer ball to sign in place of a guestbook.

The form of the exhibition mirrors that of a large-scale sporting event in that it evolves over time: “It’s a time-lapse exhibition that won’t be complete until the 90 minutes are up on Sunday, July 15,” says Park. It’s also, like the World Cup, an international endeavor: “There are other shows in Germany, the Netherlands and Russia, as well as at numerous other venues all across Switzerland,” Park writes. “Another interesting point is that there is an identical show going on right now in Seoul, Korea. The same 48 posters went up, then the remaining 16 posters were assigned to local designers there.” Posters from this event will be shown at Weltformat 18 in Lucerne and Weltformat Korea 2 in Seoul later in the year.

Lindsay Maynard, program coordinator for continuing studies at OCAD University, is one of the Toronto artists and designers participating. A former soccer player herself, she recently created a minimal pink-and-white poster for the Uruguay vs. Portugal knockout match. “We had an opening where designers came and drew names on who would do which of the remaining matches,” explains Maynard. As each match comes to a close, the wall text for each poster is filled in with the final score of the game. The show—which has a soccer ball serving as guestbook—has had a strong response. “On opening day of the exhibition we had visitors from the UK, France, Peru, Korea, South Africa and Iraq, as well as an international school come for a group visit later on,” Park states. He adds: “While sports is fun and inviting in itself, it is somewhat contained to the players and enthusiasts involved. Interpreting the matches into graphic posters gives the World Cup or the sport, rather, a new facet or context, if you will.”

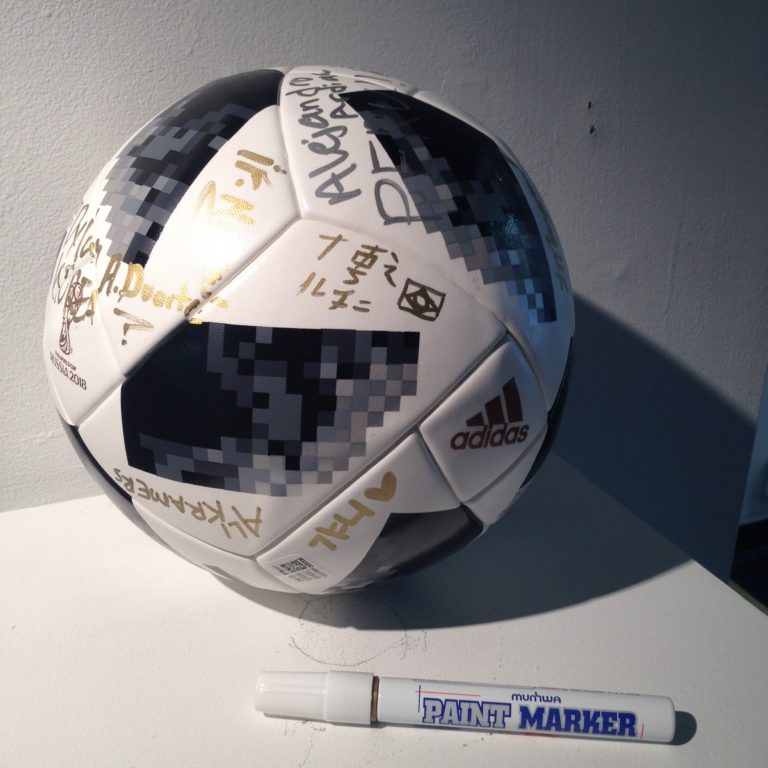

The latest edition of the INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media focuses on sports—a long-time interest of founding editor and publisher Brett Kashmere, who grew up playing hockey in Saskatchewan.

The latest edition of the INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media focuses on sports—a long-time interest of founding editor and publisher Brett Kashmere, who grew up playing hockey in Saskatchewan.

Though the World Cup only lasts about a month, artist Brett Kashmere and curator Astria Suparak are conducting an extended project on sports and art—including soccer—from January to November of this year.

Their A Beautiful Game screening program, shown at VisArts in Maryland last week, has four films related to soccer: In Refait (2009) by Pied La Biche, the artists remake, frame for frame, a video of a World Cup match between France and Germany from 1982—but in everyday urban settings, like parking lots and highway overpasses. México vs Brasil (2004) by Miguel Calderón shows a patrons in a São Paulo bar watching a soccer game on TV—a game that, unbeknownst to them, is not real, but has been edited together from prior footage. The Zidane World Cup Headbutt Animation Festival (2006) by Anil Dash presents short, fan-produced takes on an iconic soccer moment. Football (2011) by Ana Hušman looks at the first matchup between England and Argentina post Falklands War at the FIFA World Cup in 1986. But in keeping with the wider scope of Kashmere and Suparak’s 11-month sports-art project, A Beautiful Game also includes Alethea Arnaquq-Baril’s 2010 film of Inuit high kick and Paper Rad’s 2004 video game mashup about Boston Celtics hall of famer Robert Parish.

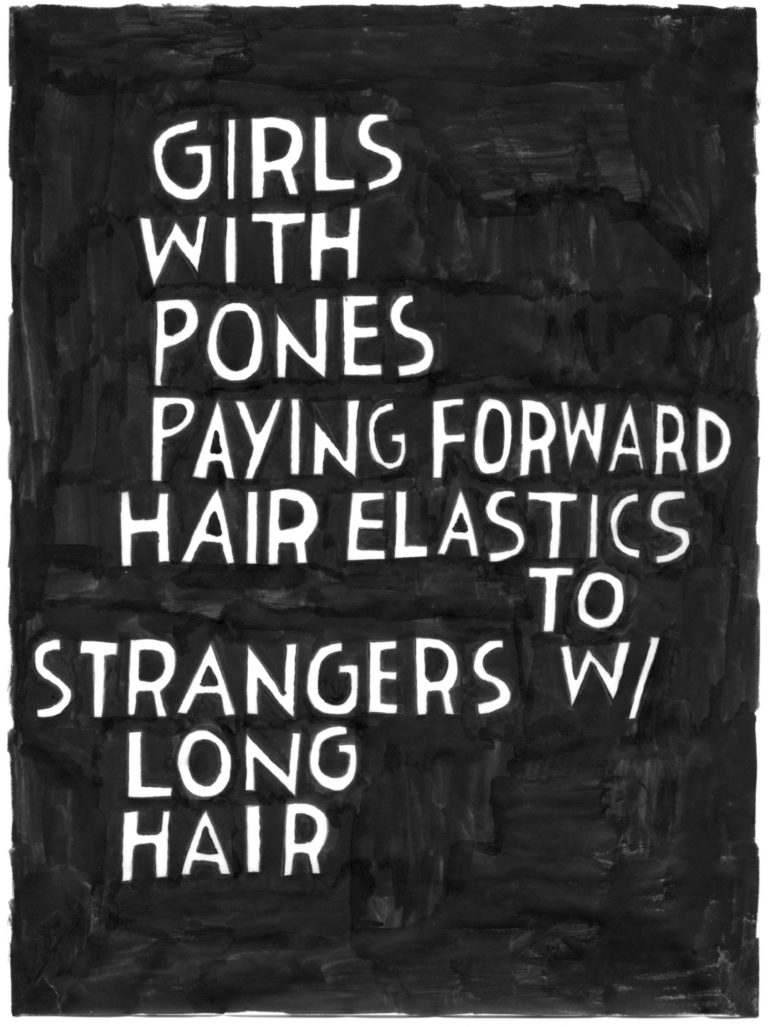

Hazel Meyer, pone economy, 2014. Ink on vellum, 25.4 x 20.3 cm. From the Muscle Panic Handbook created with Cait McKinney.

Hazel Meyer, pone economy, 2014. Ink on vellum, 25.4 x 20.3 cm. From the Muscle Panic Handbook created with Cait McKinney.

And on July 17, Kashmere and Suparak will hold a Los Angeles launch at 18th Street Arts Center for the newest, sports-themed issue of INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media, of which Kashmere is founding editor and publisher. The journal features work and writing by artists including Karen Kraven’s moire-effect photos of sports jerseys; Christina Battle’s consideration of Colin Kaepernick’s portrayal on social media; Hazel Meyer and Cait McKinney’s Muscle Panic Handbook; Germaine Koh’s Game Changers; and selections from Pasha Malla and Jeff Parker’s Erratic Fire, Erratic Passion: The Poetry of Sportstalk.

“I would say that INCITE’s Sports issue dovetails some of my interests of the past 20 years, which are experimental film and video and sports,” says Kashmere in a phone interview. “Sports has been central to my research over the past decade and at the same time I have been tracking sports’ emergence and popularity in the art world, which I think has increased in the past two decades.”

Kashmere played hockey growing up in Saskatchewan, then played basketball and coached women’s basketball, which also informs his point of view. His films include pieces on hockey violence, and he is currently working on a UC Santa Cruz PhD thesis piece looking at American football and its representation in media. For her part, Suparak is interested in how “sports are now a key part of fashion and music and celebrity culture,” she says. Among her past projects are exhibitions on fan culture, as well as a more recent survey of sports-related art, “Power Forward,” in Maryland.

“For me, sports is like a gateway or a ruse to talk about other issues,” says Suparak, “There is that constant refrain of ‘Keep politics out of sports.’ But sports has always been political—political in who is allowed to play, who gets penalized for what, what are the team names and mascots, who gets to use eminent domain to build stadiums. Recent stories of cheerleader abuse, and abuse of youth athletes by coaches, also remind us that all levels of sport are very political.”

At the same time, the ability of sports to provide moments of ecstasy and unity hold that political aspect in tension. “There is a lot that is fucked up about sports but on the other hand, this past week, I was in the airport in Calgary waiting for a flight and everyone around me was completely riveted on the Argentina-Nigeria game at the World Cup,” Kashmere says. “It reminded me that these games are so much more than just games—it’s an amazing thing to be united in a feeling with a mass of people who are both strangers and friends. There is that magical social aspect of sports which can be transcendent at times, and that is part of what I find fascinating and compelling about sports as a subject.”

Corrections and clarifications were made to this article on July 4, 2018. The updated version credits Anil Dash on an artwork, corrects accents in the names of Miguel Calderón and Ana Hušman, uses Spanish spellings for Calderón’s artwork, and states specific venues for events and exhibitions in Maryland and California.